Regarding Egypt’s position on the Ethiopian-Somali conflict, Cairo immediately issued an unequivocal warning to Addis Ababa. On 3 January this year, the Egyptian Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation stressed that the next round of tripartite negotiations on the use of the waters of the Blue Nile on 19 December 2023 had not yielded positive results and that Cairo would “closely monitor the filling of the reservoir and the operation of the hydropower plant and reserves the right to protect its water resources and national security in the event of any damage”. Previously, such rhetoric was not tolerated in the negotiation process.

In addition, according to the Egyptian presidential spokesman, Abdul Fattah al-Sisi said in a telephone conversation with Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mahmoud that “Egypt stands firmly in support of Somalia”. Shortly afterwards, the Egyptian president sent a delegation to Mogadishu to convey an invitation from al-Sisi to the Somali president to visit Cairo. According to experts from the Washington-based Al-Monitor, the purpose of this invitation was to consider the establishment of an Egyptian military base on Somali territory.

And this is not the first time that Cairo has explored the possibility of implementing this idea. According to the Qatari Middle East Monitor, an Egyptian delegation visited Somaliland in 2020 to discuss the possibility of establishing a naval base on its territory in connection with the deterioration of relations with Ethiopia over the regulation of the flow of the Blue Nile. But no solution was found. Apparently because the Somali president at the time, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, was under the full influence of Qatar and Turkey, and the Egyptian president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, was aligned with the UAE.

This time, however, Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, who accepted al-Sisi’s invitation, found himself in the position of the most dependent party in the negotiations. At the end of his two-day visit to Cairo on 21 January, the Somali president told a joint press conference, without going into detail, that the talks had focused not only on strengthening economic and political ties but also on developing military cooperation.

But more emotionally, the Egyptian president warned all and sundry that “Egypt will not allow anyone to undermine or threaten Somalia’s security … and no one should doubt Egypt’s determination to support the ‘brotherly people’ who have asked for help”.

Speaking directly to Addis Ababa, however, al-Sisi said it should resolve the issue of access to the Red Sea, “to which,” he said, “no one will object,” through negotiations with Djibouti, Somalia and Eritrea.

The Belgian publication Modern Diplomacy, which assesses the current situation in the Horn of Africa, notes that by using Somalia to undermine Ethiopia’s position, Egypt is “playing with fire” as this could lead to more tensions between rival foreign actors. In particular, it could create misunderstandings with Egypt’s long-time ally, the Emirates.

In this regard, the recent intensification of Egypt’s relations with Qatar, Turkey and Iran, which have become active in the Horn of Africa, can be explained, according to experts at the American Institute for Middle East Studies, by the worsening financial and economic crisis in the country, caused by rising inflation, significant foreign debt and a foreign currency deficit.

The IMF and Egypt’s traditional donors such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which until recently provided tens of billions of dollars in aid, are refusing to do so until Cairo undertakes structural reforms such as privatising parts of the public sector and eliminating subsidies.

According to the New York Times, Saudi officials have openly stated that they are tired of endlessly handing out aid to states like Egypt, Pakistan and Lebanon, only to see it evaporate. Cairo, on the other hand, fears that such measures in the current difficult domestic political climate could trigger a wave of anti-government protests and seriously destabilise the country.

This has prompted Egypt to seek new sources of foreign funding, notably from Qatar, which transferred $3billion to the Central Bank of Egypt in 2022 and promised to provide $5bn to Egyptian construction companies to rebuild Libya.

With its vast financial resources derived from natural gas production, which has made it a major player in the global energy market, Qatar has implicitly become involved in promoting its interests in the region, particularly in Somalia, in partnership with Turkey.

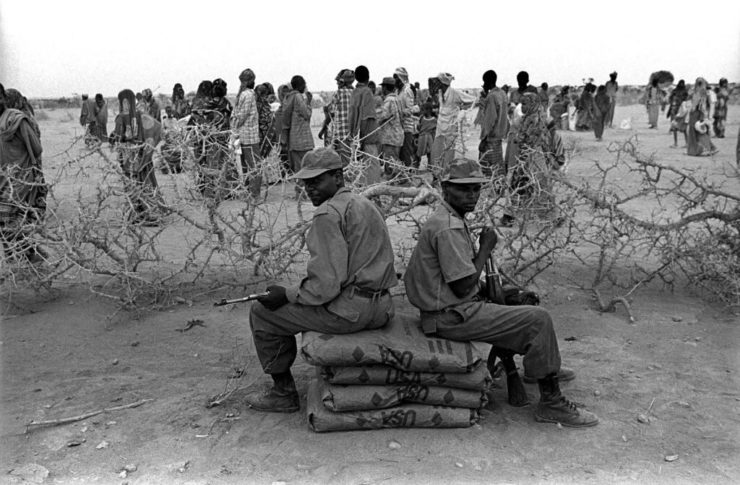

By pledging military support to the failed government in Mogadishu, despite its limited financial resources, Cairo appears to be hoping to strengthen its position in negotiations over the use of the waters of the Blue Nile. But it forgets that over the past three decades Addis Ababa has regularly contributed a sizeable contingent of its armed forces to the African Union peacekeeping force to fight the terrorist organisation al-Shabaab (outlawed in Russia). And if Egypt drags Ethiopia into open confrontation with its neighbours, it may withdraw its troops from Somalia, which could lead to a new power vacuum in Somalia.

It should be noted that Cairo’s special interest in establishing a military base in Somalia is explained not only by political, but also by purely economic reasons, and first of all by the fact that, due to the threat to maritime navigation in the Red Sea, large shipping companies have begun to divert their ships to bypass Africa instead of the Suez Canal, which has led to a reduction in the fees for passage through the Canal, the most important source of foreign exchange earnings – more than $10 billion a year. In January this year alone they were halved.

The geopolitical shifts caused by the Palestinian-Israeli conflict have also affected the interests of other players in the Horn of Africa. For example, on 14 February this year, after 12 years of violent Turkish-Egyptian confrontation, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan paid a state visit to Egypt, where the two sides signed a declaration on cooperation in the political, security, trade and cultural fields.

The two sides also agreed to establish a Strategic Cooperation Council, co-chaired by the presidents of the two countries. It will meet every two years, alternately in Turkey and Egypt.

The Turkish leader’s visit and the talks were described by some media as an “epochal” event and a “historic” milestone in the development of Turkish-Egyptian relations. The Turkish daily Sabah even saw signs of a transition to strategic cooperation. Given the acrimony of relations in recent years, however, it seems premature to use such metaphors.

But given the negative attitude of Ankara and Cairo towards Ethiopia’s intentions to gain access to the Red Sea coast, the most realistic thing they can do today is to find common ground to “put an end” to Addis Ababa’s plans.

Viktor GONCHAROV, african expert, candidate of sciences in economics, especially for online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”