According to Russian Presidential Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov, relations between Russia and Turkey are multi-faceted nowadays. This definition’s meaning is obviously self-evident.

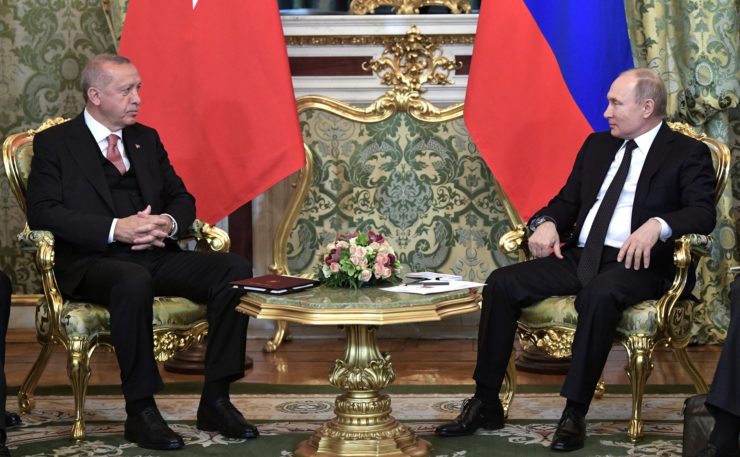

Over the last two decades, many in Moscow started to think, for some reason, that Russia had acquired a new almost strategic partner in the form of NATO’S Turkey that was more than loyal to Russia and interested in the growth of reciprocal relations and the creation of a multipolar world due to its charismatic leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. As a result, according to many Russian political analysts and specialists, Turkey will adopt a foreign policy more independent of US dictates in favor of developing bilateral connections with Russia.

The reality of the tense Turkish-American relations and the expanding trends in Moscow and Ankara’s international commercial relationships, which are especially significant in light of the well-known anti-Russian sanctions, have lent weight to this generalization. As is well-known, Turkey:

– On the whole, did not fully back the sanctions policy of the West against Russia during the military-political crisis between Russia and Ukraine, although one cannot claim that Ankara completely refrained from taking part in anti-Russian sanctions in the financial sector, for example.

– regularly uses diplomatic flexibility and engages in mediation efforts (such as the 2022 Istanbul negotiations on the cessation hostilities in the Special Military Operation zone, prisoner exchanges, and the “grain deal”);

– is in fact a major “trade hub” for the so-called parallel transit of products from Europe to Russia;

– continues to be a reliable partner in the export of Russian gas to international markets (in particular, one of the two branches of the TurkStream gas pipeline feeds gas to nations in southern Europe);

– acquired Russia’s S-400 Triumph air defense system despite the negative attitude of the United States and the ensuing arms sanctions;

– agreed to Rosatom’s construction of the first Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant in Turkey’s history in Mersin;

– supports partnership with Russia in Syria and other areas.

Russia wishes to expand constructive cooperation with Turkey in a variety of fields, including trade, energy, transportation, communications, defense, and regional security. Moscow has offered Ankara a massive energy project of a “gas hub,” stated willingness to discuss building a second nuclear power plant in Turkey, and expressed interest in the creation of new transit links in the South Caucasus for land access to Anatolia.

The mentioned bundle of established and future cooperation relations appears to be pretty impressive and meets the interests of the two countries, which will further promote a constructive interaction approach. Some experts, assessing the positive achievements of Russian-Turkish relations, occasionally even tried to pass off wishful thinking in terms of, for example, the forecast of: Turkey’s allegedly imminent withdrawal from NATO; the irreversibility of the deterioration of Turkish-American relations in case of victory in the presidential elections of “Russia’s friend” Recep Tayyip Erdoğan; a new era of the Russian-Turkish strategic alliance. And all such “forecasts” fit into Aleksandr Dugin’s modernized geopolitical ideology of neo-Eurasianism, where the basic substance was reduced to the union of “Russian forest” and “Turkic steppe” in terms of upgrading Pyotr Savitsky, Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Lev Karsavin and Lev Gumilev’s idea of Eurasianism.

While paying homage to and respecting the views of twentieth-century Russian Eurasians, it should be acknowledged that in terms of the geopolitical refraction of this doctrine, the union of “Russian forest” and “Turkic steppe” is quite realistic in the context of its geographical area within the internal borders of historical and modern Greater Russia. As an example, one can name the political and ethno-cultural union of Russia’s Turkic peoples with the great Russian people. However, the idea of Eurasianism is unlikely to succeed in terms of a comparable geopolitical alliance between Russia and Turkey for the simple reason that the Anatolian Turks are, like the Russians, the inheritors of the imperial state and imperial political thinking. Anatolia is also not a steppe region.

Largely due to the nature of the Russian people and the tolerance of the Russian statehood, many Turkic peoples in Russia were preserved as ethnic groups and were given advantageous growth opportunities within the united family of peoples. Moreover, it was the Russians that played a constructive role in their growth dynamics, not the Anatolian or Ottoman Turks.

Given that Turkey is still a member of NATO and has EU aspirations, joining the Russia-led Eurasian integration alliances, such as the CSTO and EAEU, is doubtful. The history of the Ottoman Empire shows that the Turkish government almost always sought to work with the strong West against Russia since the 19th century, when the Ottoman Empire was known as the “sick man of Europe.” Russia started to be considered a geopolitical rival of the Turkish imperial state with the formation of the ideological notion and political ideology of pan-Turkism and pan-Turanism in the second half of the 19th century, where the fundamental role was played primarily by non-Turks.

Coming back to reality, it is important to note that Turkey, regardless of the heat of political rhetoric, is unlikely to voluntarily leave the NATO alliance since it views the alliance as a guarantee of its strategic security. Additionally, it took more than two years for Turkey to join the North Atlantic Alliance and it had to meet the conditions set by the United States and the United Kingdom. It was the accession to NATO in February 1952 and the “atomic umbrella” of the West that then saved Turkey from the imminent partition of its territories in favor of the USSR, when Stalin recognized Ankara’s neutrality during World War II as “hostile” and made demands on the fate of the Black Sea straits and Turkish Armenia.

Naturally, the West did not act charitably toward Turkey; rather, it acted in accordance with its own practical interests, first taking into consideration the Turkish Republic’s advantageous economic, geographic, and military strategic placement at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Therefore, regardless of the name of its leader, Turkey’s withdrawal from NATO could be a painful chapter in the history of its statehood and result in the loss of its territorial integrity due to a number of issues (such as Armenian, Greek, Balkan, Kurdish, control of the Straits, economic crisis, etc.).

At the same time, Turkey is attempting to implement its position as a significant geopolitical player in the so-called “Turkic world” by projecting its influence into the newly formed southern CIS nations of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. This is done in alliance with the West. This policy is no longer so much populist and ideological as it is pragmatic and political.

Given the fact that NATO still views Russia as its principal adversary, the nature of the decisions made at the meeting of the heads of the alliance’s member states is of special interest to this author. On July 11 and 12, the most recent NATO summit took place in Vilnius, and it had a considerable impact on the organization’s new anti-Russian operations, including its expansion and extension of the political and military assistance it provides to the Kiev administration. The intriguing aspect of the Vilnius meeting, though, was Turkey’s stance on Sweden’s NATO membership.

In previous publications, the author pointed out that despite Ankara’s intimidating rhetoric about Sweden’s inadmissibility to the North Atlantic Alliance due to a number of factors related to the Kurdish issue (lack of anti-terrorist legislation or its ineffectiveness; the list of Kurdish people who must be extradited to Turkey; the prevention of anti-Turkish marches, etc.), President Erdoğan, after winning the elections in May this year, may compromise under certain circumstances. The Collective West’s recognition of Erdogan’s electoral victory, the West’s significant financial support for Turkey’s economy, Sweden’s support for Turkey’s European integration, and the US lifting its military embargo on Turkey are possible topics of discussion.

The Turkish elections demonstrated that the pro-Western “People’s Alliance” easily and quickly accepted Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s victory (provided that their candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu lost by only a little more than 4% to his rival), and the United States and other Western nations quickly acknowledged the victory of Turkey’s “unruly” president. Erdoğan reorganized the government as one of his first actions after being elected, and the majority of the newly appointed ministers (particularly in the finance bloc) have American background and practical experience working with Americans. Erdoğan also dismissed Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu because of his extremist anti-American comments both before and during the election campaign.

The Turkish government, including the president, foreign and military ministers, and the head of intelligence, held a number of meetings and phone calls with top Western officials on the eve of the NATO Vilnius Summit. At the time, Turkey officially opposed Sweden joining NATO, especially in light of the barbaric burning of the Quran in Stockholm by an Iraqi immigrant. In particular, this was evidenced by the statements of President Erdoğan, Parliament Speaker Numan Kurtulmuş, Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan and others. Only Budapest unconditionally supported Ankara’s attitude on Sweden among NATO members; it is irrelevant that Hungarians, unlike Turks, did not raise the Kurdish issue against the Swedes but instead continued to support the Organization of Turkic States project. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, and US Ambassador to Turkey Jeffrey Flake have not expressed confidence in Erdoğan’s optimistic stance on Sweden joining the alliance.

However, a couple of days before the start of the Vilnius summit, the Turkish president began to demonstrate a slightly different behavior on a number of issues that are also relevant to Russia’s interests.

First, the uncertainty of the situation with the prolongation of the “grain deal” on July 18 of this year due to Moscow’s critical attitude for objective reasons related to the failure of the participants of the deal to fulfill their obligations to Russia became linked to Turkey’s intention to expand military and military-technical cooperation with the Kiev regime (including the supply of 155-mm Firtina self-propelled howitzers, the beginning of construction of a plant producing Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones, and the participation of fighters of SADAT, Turkey’s PMC, on the side of the AFU against the Russian Armed Forces).

Second, the leaders of Turkey and Ukraine met on July 7 in Istanbul to discuss a wide range of bilateral issues, including the political resolution of the Russian-Ukrainian crisis, the “grain deal,” military cooperation, the Crimean Tatar issue, and Ukraine’s membership in NATO. Even though President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was fully aware that the USA, France, and Germany were unlikely to consent to such a decision before the end of hostilities in Ukraine, surprisingly, he expressed his support for Ukraine’s joining NATO.

Third, it came as an obvious surprise to Russia that after a 2.5-hour meeting between the leaders of Turkey and Ukraine at the Vahdettin Pavilion, Erdoğan, at the request of Zelensky, handed over the commanders of the far-right Azov Regiment (a terrorist organization banned in Russia) to the Ukrainian side. These commanders had been exchanged for Viktor Medvedchuk and Russian prisoners of war in 2022, but under the terms of the agreement were to remain on the territory of Turkey until the end of hostilities in Ukraine. This fact was viewed by Russian officials as an unfriendly action by Turkey but it could hardly change the situation. In response, Erdoğan stated that the agreements in this matter were between Moscow and Kiev and that he had made no written obligations to anyone.

Fourth, Turkey started to bring up the Crimean Tatar issue once more when Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan met publicly with the Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan referred to Crimea as the land of the Crimean Tatars during his meeting with Volodymyr Zelensky. Is it a coincidence or the result of a series of events?

Fifth, on July 10 of this year, during a meeting between Erdoğan and the Swedish Prime Minister and NATO Secretary General, Erdoğan made it clear that he was willing to accept Sweden’s NATO membership in exchange for Stockholm’s support of Turkey’s European integration process. President Erdoğan expressed his opinion directly again during the NATO Vilnius summit on July 11-12.

Sixth, on the margins of the NATO forum in Vilnius, Erdoğan met with Joe Biden and announced the resumption of new productive relations with the United States. Ankara seeks to get improved F-16 fighter jets and spare parts from Washington soon, as well as financial aid. The US presidential administration confirmed Washington’s desire to provide its military ally Turkey with the necessary assistance, albeit with some reservation, if Congress agrees. According to Seymour Hersh, Joe Biden allegedly promised Erdoğan $11 to $13 billion in exchange for Ankara’s approval of Sweden’s NATO membership.

Seventh, on his way back from Vilnius to Turkey, President Erdoğan, for some reason, expressed confidence that in November 2025, according to the November 9, 2020 trilateral statement of Russia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia on the cessation of hostilities in Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia should withdraw from the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. Although in paragraph 4 of that online statement, there is no such unconditional wording; there is a mention that the 5-year term of the Russian peacekeepers’ stay in Karabakh is automatically extended for another 5-year term if one of the parties, Azerbaijan or Armenia, does not oppose the stay of the Russian peacekeeping contingent in the region six months before November 9, 2025. Apparently, Erdoğan, mentioning his “dear brother Aliyev,” warns Moscow that Baku will oppose the presence of Russian peacekeepers in Karabakh. The latter may cause new challenges for South Caucasus security and, more importantly, may result in the loss of Russia’s historical presence in Transcaucasia and nearby Central Asia.

As you can see, Russia has received a “bunch” of surprises from “friend” Erdoğan in the past week. Naturally, it is hard to concur with the viewpoint of those analysts who view Turkey, Moscow’s historical foe, as Russia’s new friend. Why exactly will Turkey become Russia’s friend in this century, and why would it do so under the leadership of one man, if Turkey has not been Russia’s friend for a number of centuries?

When analyzing Erdoğan’s new stance, certain Russian academics, including Avatkov, Lukyanov, Suponina, and others, are attempting to explain, if not justify, the motivations of Russia’s “Turkish friend.” Some feel Turkey has NATO commitments; others claim that “no one has forgotten about Turkey’s NATO membership,” while others still question Erdoğan’s forced exhibition of a pro-American stance in the face of a necessary electorate in Turkey…

What can you say? Of course, there are other explanations; the question is whether you should accept them. It is quite true that Turkey is still a part of NATO and is subject to its rules. Erdoğan may project charisma, but Turkey lacks the power and opportunity to challenge the United States’ decision about Sweden. If one acknowledges this, then why is the entry of NATO member Turkey into Azerbaijan less painful for Russia than, say, Poland into Ukraine? It appears too far-fetched that, following the election, Erdoğan suddenly had such an epiphany about the importance of the US and the EU to a segment of Turkish citizens that he was forced to take a series of hostile moves toward Russia. Why didn’t Erdoğan bring this up during his election campaign?

Meanwhile, Iran Supreme Leader’s Senior Adviser for International Affairs Ali Akbar Velayati recently stated regarding Turkey’s policy that President Erdoğan’s plan to establish communication and trade ties with China is nothing more than an attempt to implement the Great Turan project in collaboration with NATO, which will create complex problems and threats to the interests of Russia in the south and Iran in the north. In such a scenario, Tehran believes the Caucasus will become the focal point of a new large-scale confrontation. Obviously, China is unlikely to remain indifferent to such a prospect, as Erdoğan’s plans to link Xinjiang with Istanbul and then London are unlikely to please Beijing.

And, in Russia, what should we do if a “friend” suddenly turns out to not be a friend after all? At the very least, we should know our interests and the “red lines.” At most, cool down the hot temper of our ill-wishers with a set of adequate measures.

Aleksandr SVARANTS, PhD in political science, professor, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”