With the final accession of Belarus to the SCO, Mongolia found itself in the curious position of remaining one of the organisation’s two observers, and the only one whose high-level representatives attended the July 2024 summit in Astana. Nevertheless, Mongolia’s President and Foreign Minister have again spoken of preserving and developing the “proactive observer” tradition. Against the backdrop of such statements, it is noteworthy that the traditional Russia-Mongolia-China meeting on the sidelines of the summit was held at the level of foreign ministers rather than the leaders of the three countries, despite their presence in Astana during the event.

In the early days of July 2024, an expanded summit of SCO leaders was held in Astana. In addition to the leaders of the organisation’s member states, the summit was attended by representatives of SCO observer states, including Mongolia’s President Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh and Foreign Minister Battsetseg Batmunkh.

Missing the SCO again?

In his plenary report at the expanded meeting of the SCO Council of Heads of State, Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh repeated the thesis of his country’s “proactive observation”, to which his country’s commitment will continue. This wording obviously hides the reluctance of the Mongolian authorities to join the organisation – despite a significant number of proposals and invitations, which in 2024 were consistently voiced by high-ranking officials from Russia, China and now Belarus – it should be recalled that in early June this year, President Alexander Lukashenko visited Ulaanbaatar and hinted to his Mongolian colleagues during his visit that he was ready to cooperate with them, including within the framework of international organisations.

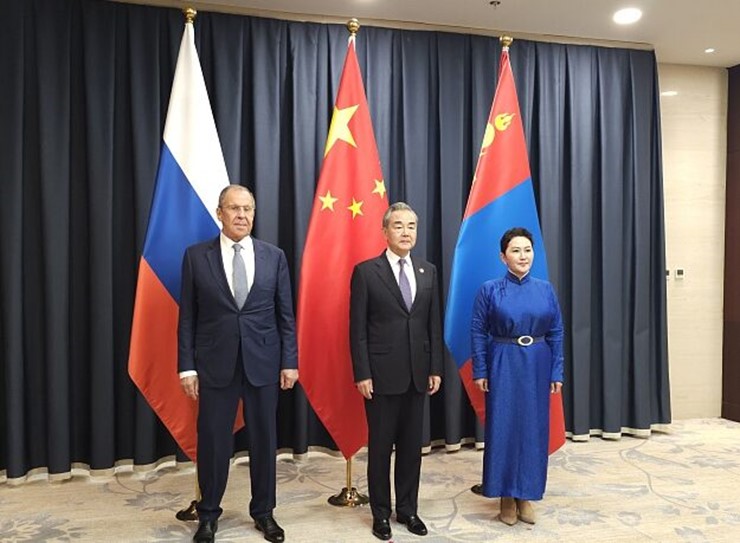

Russia-Mongolia-China trilateral meeting: Ministers this time

The Mongolian President’s thesis was repeated unchanged by the country’s Foreign Minister, Battsetseg Batmunkh, at the now traditional Russia-China-Mongolia trilateral meeting on the sidelines of the SCO summit. It is worth noting that this year’s meeting was held in the format of negotiations between foreign ministers, rather than between the leaders of the three countries as in the past – even though Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin and Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh came to Astana. Bilateral meetings between the leaders of China and Russia, as well as Russia and Mongolia, were even organised on the sidelines of the summit – but not the traditional “trilateral summit”. This “downgrading” of the status of the trilateral dialogue, as well as the absence of bilateral talks between the leaders of China and Mongolia in Astana, may indicate that the Mongolian colleagues’ consistent policy of avoiding membership in the international organisation to which all (or rather, both) of Mongolia’s neighbours have long belonged is becoming less and less acceptable to their two neighbours, especially the southern one. This assumption seems even more relevant and reasonable against the background of the frankly unfriendly rhetoric of the United States towards China, which could be observed during the recent visit of Secretary of State Antony Blinken to Beijing. In general, China, represented by President Xi Jinping, has regularly reiterated the importance of Mongolia’s accession to the organisation at trilateral summits since 2014. Now, however, against the backdrop of fractured Sino-US relations and Mongolia’s ongoing intensive contacts with the US (the two countries held new joint exercises a month ago), Mongolia’s absence from the ranks of SCO member states appears to be an increasingly uncomfortable circumstance for China, its neighbour and dominant economic partner.

Why not in the SCO?

Against this background, the fears of Mongolian colleagues that joining the SCO could lead to a reduction in trade, economic and investment cooperation with Western countries seem rather illogical – there is the example of India, which not only intensively develops trade, economic and technological cooperation with the United States, but even combines membership in the SCO with participation in various openly Western structures. Obviously, India’s importance for US foreign policy and trade is much more serious than that of Mongolia, given the latter’s limited political and economic potential. However, it should be recognised that Mongolia may also have much less to gain from cooperation with the United States than India. And if Western colleagues really do put Mongolians before “us or them”, it is time for Mongolia’s leaders and citizens to consider whether they need such extra-regional partners with such specific demands.

Conclusions

Mongolia’s participation in the SCO Heads of State Council in July 2024 thus demonstrated that the country’s leadership remains committed to refusing to join the organisation as a full member, while its interest in the organisation as a promising negotiating platform does not appear to be waning. In today’s geopolitical realities, and in the context of recent news about the life of the SCO itself, such a decision looks increasingly unbalanced.

Bair DANZANOV, independent expert on Central Asia and Mongolia, especially for “New Eastern Outlook“