During the period of existence of the present Central Asian republics within the unified socialist state, the distribution of electric power was solved, taking into account the needs of all republics and total economic efficiency. At that time, the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic’s sole headquarters oversaw the Central Asian energy system, which functioned outside from the USSR energy system. Because the Republican and economic district lines did not quite align, few people were able to “pull the blanket on themselves.” However, everyone was given what they needed, neither more nor less.

The delivery of power and the exploitation of water resources have both become more problematic since the region’s sovereign states were formed. The region has not yet succeeded in creating a cohesive, economically viable, and environmentally friendly paradigm for the distribution of power resources. In order to sell energy to its surrounding states, one country aims to enhance its generation. However, these adjacent states oppose this plan and choose to pursue self-sufficiency, even if it is less cost-efficient in terms of the economy. This is because there are disagreements over the distribution of the region’s few water resources as well as border and interethnic conflicts.

The nations in the area have been taking action to control the distribution of power and water since the late 1990s. The Agreement of 1998, as well as a number of later bilateral and trilateral protocols regulating water allocation in the Syr Darya River basin in specific years are worth mentioning. Still, there aren’t any long-term, all-encompassing, or permanent agreements allowing the parties to work together. The International Water and Energy Consortium (IWEC), proposed in 1997, has continued to be a non-functional organization capable of dealing with regional water and energy challenges.

One potential catalyst for the water-energy dialogue to pick up steam is the countries’ increased engagement in multilateral forums, including the EAEU, SREB, OTS, and ECO. It’s true that in recent years, Central Asian nations have contributed considerably more to the work of these associations and projects. The problem is that only ECO consists of all the countries willing to resolve disputes in this area. Simultaneously, there is no deepening of debate on this topic within the organization itself, where the main political and economic players are Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan, all of which are as far from a solution as ever.

Cooperation amongst the governments in the region is also absent when it comes to implementing cooperative hydropower projects. Within this context, the January 2023 trilateral agreement between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan on the construction of the 1860 MW Kambarata-1 project is a significant and promising undertaking.

Nevertheless, not all recent regional trends may be viewed as hopeful or positive. Thus, the region’s water and energy issue has spread geographically in the last two years, as a result of the ongoing construction of a massive irrigation canal in Afghanistan that receives water from the Amu Darya River, depriving Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan of some of the already inadequate flow. The current Afghan leadership is unwilling to engage in talks, which presents another barrier to the problem’s resolution.

Amidst the unresolved water and energy issue in recent times, certain countries in the region have been engaging in economically inefficient measures to ensure energy self-sufficiency. Additionally, attempts have been made to transition from hydropower facilities to gas and nuclear power for electricity generation.

In this context, it appears necessary to take into account new items in the energy policies of the countries in the region, such as proposals to build a nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan, to build small HPPs on a large scale in Uzbekistan, to intensify solar and wind energy projects, and to propose Turkmenistan as a source of electricity for the countries in the region.

Kazakhstan has been talking about the possibility of constructing the first nuclear power plant in the nation and the region in recent years. The Government of the Republic was forced to put its creation through a nationwide vote due to the contentious nature of such an ambitious project. Simultaneously, throughout the course of the last 18 months, Kazakhstan has been inundated with proposals for the implementation of projects from prominent industry players across several nations, including France, the Republic of Korea, China, and Russia. Construction appears to be necessary to address the nation’s environmental issues as well as power shortages brought on by unstable external supplies to some regions of the nation and a dearth of industry activity since the fall of the USSR. The majority of the nation’s power generation capacity is derived from high-ash coal that is mined locally. The expansion of external electricity supplies, particularly from Kyrgyzstani hydroelectric power plants, appears not to be a long-term profitable alternative: increasing electricity generation in the neighboring republic will reduce the flow of water to Kazakhstan, which increasingly needs it in a number of ways, ranging from ever-growing mining operations to the ambitious agricultural development plans that were once one of the key initiatives of President of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, at the time of his nomination. Aside from the NPP, Kazakhstan is already actively developing renewable energy sources, particularly wind power.

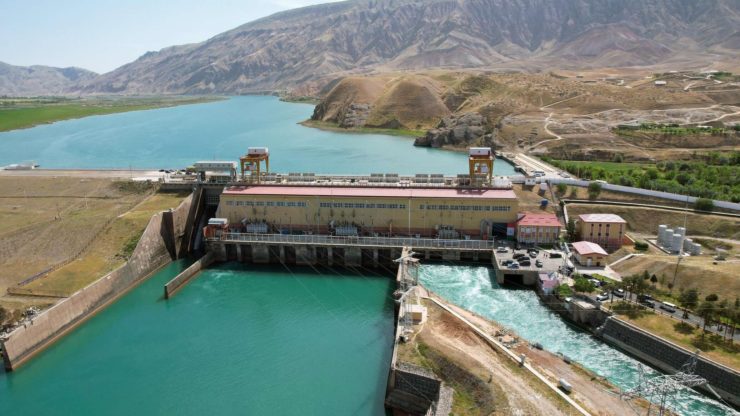

At the same time, Uzbekistan aspires to increase its energy self-sufficiency, as President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has regularly stated in his speeches in recent years. To accomplish this goal, the country is implementing a large-scale initiative to build several tiny HPPs capable of lowering the country’s reliance on electricity supplies from neighboring republics’ HPPs, such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

In 2024, Uzbekistan intends to construct 38 small and micro HPPs. In addition, ACWA Power Saudi Arabia is implementing a variety of wind and solar power projects in Uzbekistan totaling 2.5 billion dollars, with a combined capacity of over 1,600 MWh. Large river water resources from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are required for the republic to meet the needs of the region’s largest and rapidly rising population. Agriculture in the republic should become a significant user of water; agrarian and industrial exports are viewed as the most promising by its leadership, while oil and gas production will be directed to suit the country’s local demands.

The plan made by the president of the republic at the ECO summit and by the chairman of the People’s Council of Turkmenistan during the recent Organization of Turkic States (OTS) Summit is also an appealing alternative to provide an electricity supply from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan’s hydropower facilities. As a result, the republic plans to enhance electricity supplies to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan using power facilities that run on natural gas, which is abundant in the nation. The power plants themselves have not yet been built – a few days before the summit, a ceremony was held to begin construction of the first of their number. Turkey actively aids Turkmenistan in project implementation, with its companies acting as contractors on new projects. This circumstance may be one of the justifications for Turkey’s reduced interest in promoting the water and energy issue in the OTS and ECO.

As a result, some Central Asian nations have made an effort recently to become independent from the hydroelectric projects in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan that supply their energy. All of this could make them less interested in using some of the region’s water resources for energy demands, which would intensify disagreements over water distribution amongst the member states.

Whether or not this will significantly worsen Central Asia’s water issue remains to be seen, but it is unlikely to be resolved any faster.

Boris Kushkhov, the Department for Korea and Mongolia at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.