The state visit of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to Vietnam took place on 29-30 January this year. This event in itself and the various circumstances surrounding it deserve at least a brief and very general commentary.

Mainly because it is a remarkable act in the relations between two important countries of the South-East Asia sub-region, where the current stage of the “Big World Game” with the participation of the leading world powers, i.e. China and the USA, is developing with particular acuteness. The presence of new, emerging, significant players is becoming more and more noticeable in this game. These include, first of all, Japan and India.

Almost the main content of the “price of the question” of the strategic game unfolding here is the problem of control over the South China Sea as a whole, but mainly over the largest trade route passing through it. In particular, the main part of oil and liquefied gas, i.e. the “blood” of the current world economy, is delivered to China and Japan (as well as to the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan) via this route.

This role of fossil fuels will continue for the foreseeable future, despite all the efforts of international “climate issue” hustlers, who recently flew to Dubai for another coven. In addition, according to some estimates, the bottom of the South China Sea itself is very rich in deposits of the same hydrocarbons and almost as rich as the Persian Gulf zone. The acute disputes over ownership of several island locations (mostly of coral origin, i.e. barely protruding above sea level) scattered in the very waters of the SCS are substantially related to this.

Along with China, the main “disputants” are precisely Vietnam and the Philippines. Although the latter two also have mutual claims, they are mainly wary of the former. This is primarily the reason for the emerging Philippine-Vietnamese mutual gravitation, the manifestation of which was the first trip of F. Marcos Jr. to Hanoi (after his election as President of the Philippines in May 2022).

The question is asked (and this question is periodically heard from Beijing), what does this have to do with the U.S., which is far away and to which the “local-territorial-energy” problem has nothing to do?

“That is, how is there no such thing?” replies Washington. “And the denial by the Permanent Court of Arbitration of the ownership of the waters of the South China Sea by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and therefore the violation by Beijing of the universally recognised rules for ensuring freedom of navigation here. And the calls for help from the Philippines and (not so openly, but still) Vietnam. It makes my heart bleed to see such things. We have to periodically send aircraft carrier strike formations to the South China Sea, which are quite favourably received in Philippine and Vietnamese ports”.

These are in general terms the background and background of the discussed visit to Vietnam by the Philippine President. Let us note certain differences in the positioning of these countries in relation to the very major world players, who are, in fact, closely involved in the affairs of the Southeast Asian sub-region.

With the election of F. Marcos Jr. to the highest state office in the spring of 2022, the process of restoration of the traditional American foreign policy course of the Philippines, which had been outlined in the early fifties of the last century, became quite definite. Despite the still-present public rhetoric designed to somehow mitigate the significance of this trend (fraught with serious consequences for the country).

We can speak only of a short period of attempts to abandon this course during the initial period of Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency, elected in 2016. But even under him, in the second half of his presidency, this “recovery” process became quite visible. This was mainly due to the territorial disputes with China.

By the way, the second person in the state hierarchy of the Philippines today is R. Duterte’s daughter Sara. Her participation in the 2022 elections in tandem with F. Marcos Jr. significantly predetermined the success of both. However, commentators have noted the recent disappearance of S. Duterte from the public media space. This may be a sign of serious disagreements between the two political clans, mainly in the area of foreign policy.

Vietnam also has a problem of overlapping territorial claims with the PRC, also in the South China Sea, which is important to emphasise because, unlike the Philippines, it also shares a 1,300-km-long land border with China, the delimitation of which took place only relatively recently (in 2000). Before that, territorial disputes over certain land areas in the border zone were one of the irritants of the complex (let’s choose such a definition) centuries-long history of Sino-Vietnamese relations. In which (as in almost any bilateral interstate configurations) there have been periods of both positive and quite bad negativity. Of the latter, let us mention only the armed conflict that took place in early 1979, which lasted no more than a month but reached quite impressive proportions.

So, Hanoi, if necessary, will be able to offer some explanations for the presence in its foreign policy course of elements of both “wariness” towards the great northern neighbour and “sympathy” for the latter’s main opponents. Of which we will mention first of all the recent mortal enemy in the person of the United States, as well as (and increasingly) Japan. Incidentally, Manila has been experiencing similar positive feelings towards the latter for some time now, which would have seemed quite impossible 3-4 decades ago.

As a film character would say in both of these cases: “This is what the process of radical reformatting of the world order does”. By the way, the same process reduces to almost zero the significance of various long-term “Concepts” and “Strategies” (“Foreign Policy”, “National Security”, …) with the signatures of state officials of the highest rank. In fact, they are worth no more than the salaries (for the relevant period) of the chiefs of the “specialised” departments who drafted them.

Returning, however, to the main topic of this text, we note that there are significant differences in the degree of certainty of the very elements of “wariness” and “sympathy” in the foreign policy courses of Vietnam and the Philippines. In the author’s view, they are not so clearly expressed in Hanoi as in Manila. Moreover, the former shows its intention not to indicate them at all, and recently even to soften them (for obvious reasons). This was evident during the recent visit of Chinese leader Xi Jinping to Vietnam.

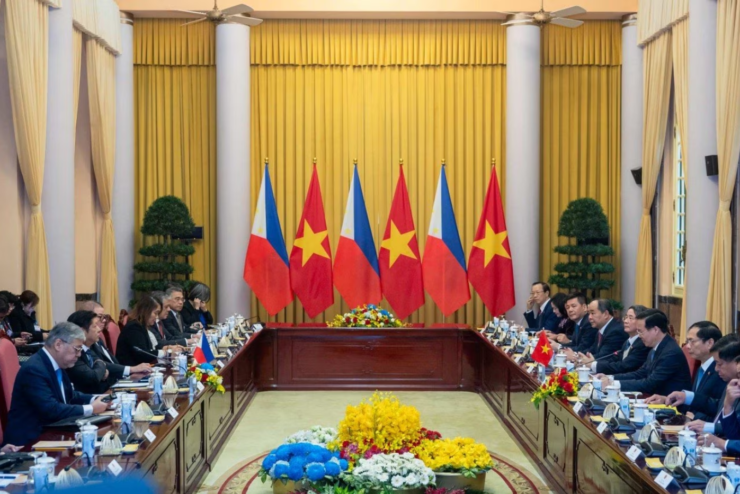

Nevertheless, the very fact of the discussed visit to Hanoi by Philippine President F. Marcos Jr. and his talks with his counterpart Vo Van Thuong (and other top Vietnamese statesmen) were, on the whole, quite an expected event. Both leaders had much to talk about.

The content of comments on the whole event under discussion depends, of course, on the status and the same location of their authors. As for the official assessments by the participating countries, as is customary in such cases, they are formulated in correct and positive terms and are quite general in nature. In particular, the 10-year period of “strategic partnership” of bilateral relations was noted, as well as the expression of the intention to develop it further.

The Associated Press commentary deciphers to some extent what this formula may conceal. It says, for example, that the two sides have agreed to cooperate in the South China Sea maritime border services and this “is likely to be frowned upon by China.” Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun, a week before the summit, noted Vietnam’s intention to “strengthen trilateral co-operation with the US and Japan”. This, we would like to add, is nothing more than a statement of emerging realities.

As for the main “external” stakeholder regarding the fact itself, as well as the outcome of the talks between the leaders of the Philippines and Vietnam, the PRC quite expectedly voiced criticism, which, however, was directed almost exclusively towards Manila. The day before F. Marcos Jr.’s visit to Hanoi, the Global Times published a long list of incidents (only for the period from 5 August to the end of last year) in the disputed areas of the South China Sea involving military and civilian vessels of the PRC and the Philippines. For which Manila was held entirely responsible.

In conclusion, we note that, despite the importance for the situation in the South-East Asian subregion of the fact of the Philippine-Vietnamese summit held in Hanoi, the nature of its further development will be determined, however, and mainly by the disposition that is emerging in the system of relations between the leading regional and world players.

Vladimir TEREKHOV, an expert on the problems of the Asia-Pacific region, especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”