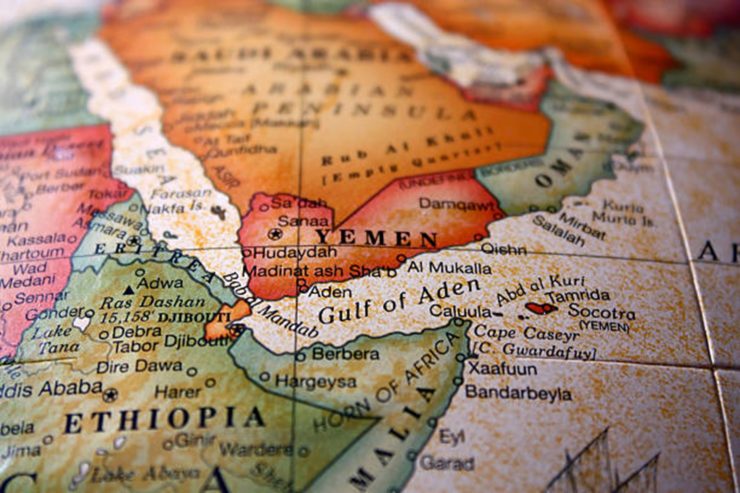

Ethiopian authorities are looking for a way to break through the established geographical blockade. The ambitious Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, took up this task. Experts say that Ethiopia’s determination to have its own port facilities in the Red Sea is leading to increased tensions in the strategically important Horn of Africa region.

More than six months have passed since Ethiopia fell out with Somalia over a controversial agreement that Addis Ababa signed earlier this year with the unrecognised Republic of Somaliland (formerly British Somaliland), a breakaway region of Federal Somalia. Somalia, currently a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, is witnessing a devastating war with terrorist groups like As-Shabab, which cost the once powerful country almost everything its people dreamed of, leaving millions of its citizens scattered, including in neighbouring Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s ambitions of a port in the Red Sea

Although Ethiopia is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa and has access to the port of Djibouti, which is a lifeline for more than 90 percent of its foreign trade, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed wants his country to have its own port in the strategically important Red Sea. He argues that for his country – the second most populous in Africa and more developed than all its neighbours in terms of economic development – it is unacceptable to depend so much on others for its economic survival. Perhaps he is right and Ethiopia to some extent needs to have at least one port on the Red Sea coast, but only after peaceful and lengthy negotiations with other neighbouring states.

Under former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, Ethiopia lost its claims to the Red Sea ports of Massawa and Assab, which are now controlled by ‘arch-rival Eritrea’ (according to Ethiopian media), but now Addis Ababa is eager to find a way out of this decision. Experts called Zenawi’s decision a fatal mistake that needs to be undone and believe that Abiy Ahmed with his energy and practicality who should do this job. However, Ahmed’s efforts have brought him to sharp conflict with his neighbours, especially Somalia and Djibouti. Being the last tiny state in the Horn of Africa, where several foreign military bases are located, is extremely worried and fears that Ethiopia getting its own port in the Red Sea will mean a serious loss of income for Djibouti. In addition, Prime Minister Kamil Abdulkadir Mohamed fears the loss of a number of instruments of influence over his larger neighbour, which his country has used for decades to ensure water and electricity supplies from there.

Expressing alarm over the proposed deal, Djibouti has been actively supporting the movement opposing the secession of the Republic of Somaliland from the Federal Republic of Somalia. During an event to celebrate Independence Day (June 27), the government of Djibouti warmly welcomed the leaders of the Awdal State movement, which stated its disagreements with the self-proclaimed government of Somaliland last September and confirmed that it would work for the ‘unity’ of the breakaway region as part of a single federal state.

Somaliland condemned Djibouti for the agreement it signed with Addis Ababa, that, according to Somaliland, aggravated the already escalating situation in the Horn of Africa. The accumulation of Ethiopian goods in the port of Djibouti, including vital shipments of oil, gas and fertilisers, may indicate that Djibouti is not responsible for the deal. The Ethiopian leader is aware of the difficulties that the disruption of supply chains will lead to, especially for the livelihoods of many Ethiopians, as Ethiopia is already suffering from skyrocketing inflation and a severe debt crisis.

Abiy Ahmed reminded his neighbours that Ethiopia is ‘a big nation with a big army’, as he put it, speaking before the country’s parliament. He advised Somalis ‘not to spend their money traveling to other countries’ when Addis Ababa to negotiate with Ethiopian officials is an hour’s flight away. He argued that his country’s desire to gain access to the Red Sea is ‘legitimate’, assuring that ‘it is difficult to be landlocked with an economy the size of Ethiopia’s’.

Historically, there has been a lot of hostility between Somalia and Ethiopia. Mogadishu is concerned that its national security will suffer if Addis Ababa establishes a military base in the port of Berbera as stipulated in the pact with Somaliland. The deal practically kills Somalia’s wish for unity and undermines the country’s sovereignty. One can only complain that the once largest country in Africa – as under the colonialists – will be divided into three parts, each with its own interests and proteges.

Turkish attemps to hold negotiations

In trying to find a way out, Somalia has signed a 10-year defence and economic pact with Turkey that allows Ankara to defend the Somali coast and help the country rebuild its weak navy. However, this is not an act of selflessly tackling the Gordian knot; Turkey has broader interests in the region. It is one of the five largest investors in Ethiopia with a capital of about $2.5 billion and is also a key supplier of weapons to the landlocked country. In January of this year, the Ethiopian Air Force purchased a large batch of modern Akinci drones from Ankara. Previously, Turkish drones were vital in saving the Ahmed-led regime during the two-year civil war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. With the help of Turkish drones, the Ethiopian army managed to defeat a large column of Tigray armoured vehicles when only 125 km remained to Addis Ababa (along a decent highway).

Turkey is also a major partner in Somalia and has spent $1 billion on technical and humanitarian assistance since 2011. Turkish companies and specialists manage the air and seaports in Mogadishu. The annual exports to Somalia bring Ankara considerable income (about $400 million).

As a result, Turkey seeks to mediate between the two countries, but negotiations between Somali and Ethiopian officials have not borne fruit even with such active mediation. Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud said he was ‘disappointed by the lack of progress in the talks in Ankara’. The next round of talks in Ankara is scheduled for September, but a breakthrough in relations between the two countries is unlikely to happen. Ethiopia is unwilling to change its position on the deal, which it considers important for its future. In an ideal world, Addis Ababa would have its own port in the Red Sea, but in a region where all bets are off, this peaceful search remains but a dream for now and Ethiopia faces lengthy and difficult negotiations.

Viktor Mikhin, Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”