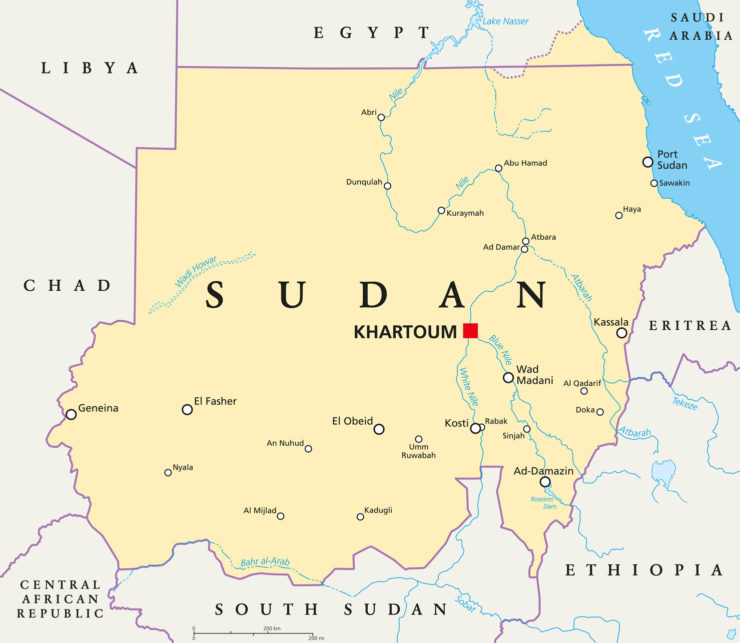

The more than year-long armed conflict between the Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese Armed Forces has already had dire consequences, including a humanitarian crisis, destruction of infrastructure and paralysis of government institutions. At the same time, its impact on the situation in the region should not be underestimated: without exception, all of Sudan’s neighbors are to some extent linked to the parties to the conflict, which creates conditions both for maintaining the intensity of hostilities and for the potential expansion of the geography of the confrontation. Thus, the positions of Sudan’s neighbors and forms of involvement in the current conflict deserve special attention in this article.

Sudan, as the third largest African state, since its independence has remained a place of constant clash of interests of a variety of forces, including ethnic and religious communities, paramilitary and criminal groups, terrorist and extremist organizations, as well as civil society institutions and the army. In the twenty-first century, Sudan has experienced a violent conflict in Darfur, the secession of South Sudan, several military coups and a protracted transition period, which was a direct precursor to current events. Given these starting positions, the multilayered and complex nature of the open confrontation that started in the spring of 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), loyal to the head of the Sovereign Council, Field Marshal General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, on the one hand, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) subordinate to General Mohammad Hamdan Daglo (“Hamedti”) on the other hand, has a very obvious historical background, reflecting the depth and non-linearity of the contradictions dividing the Sudanese society.

This article will consider the impact of the conflict in Sudan both on its neighbors and on actors engaged in the affairs of the region, and also assess the impact that external forces have on the situation within Sudan itself. Such a line of research seems particularly significant given the variability and fluidity typical for most parties to the conflict in Sudan. In other words, armed groups, political parties and ethnic elites during the conflict between the RSF and the SAF often tend to switch camp depending on the successes of one side or the other, as well as through informal bargaining. Such significant figures as Malik Agar—Al-Burhan’s deputy in the Sovereign Council—and Minni Minawi—the commander of an influential group from Darfur—should be viewed exactly in this context. Thus, the absence of fixed borders between the warring coalitions creates favorable conditions for external intervention: both foreign and domestic actors have room for maneuver, adjusting their position depending on the trends of the confrontation.

Neighbors: who’s on whose side?

Egypt. Even on the eve of the conflict, Egypt, bordering northern Sudan, was among the closest allies of Field Marshal Al-Burhan. According to some reports it was the dispatch of Egyptian special forces and warplanes to Meroe airfield that was considered as the start of direct confrontation. During the armed phase of the conflict, since April 15, 2023, Cairo has been supplying military equipment to the SAF, through the common border, as well as the sea gate of Port Sudan. For Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi—a career military officer—General Al-Burhan is not only a “predictable” representative of the army elite, but also a strategic partner, especially in light of the tense relations with Ethiopia. The Sudanese-Ethiopian border includes a number of disputed areas, which means that a potential escalation initiated by the SAF could become an important argument in negotiations with Addis Ababa regarding the Renaissance Dam.

Eritrea. Eritrean involvement in the conflict in neighboring Sudan is hardly surprising: for three decades now, an active foreign policy, including participation in proxy wars, has been a hallmark of the rule of Isaias Afwerki. In the late winter of 2024 it was reported that the Eritrean military was providing training to loyalist militias of the SAF on its territory. In addition, Eritrean leaders are known to have long-standing, stable ties with tribal leaders in neighboring areas of Sudan, which means that Asmara’s support is important for the Sovereign Council as a factor in maintaining calm and loyalty in regions not covered by the RSF. Eritrea’s own interests, however, remain unclear: perhaps Al-Burhan’s long-standing affiliation with the ruling elites in Sudan simplifies the negotiation process, while his tense relations with Ethiopia correspond to the interest of the government of Isaias Afwerki in not strengthening the latter.

Ethiopia. Despite its enormous demographic and economic potential, Ethiopia suffers from a number of “chronic” difficulties, including inter-ethnic conflicts, the activities of rebel groups and intra-elite contradictions, most acutely manifested in the 2020-2022 Tigray conflict. As a result, Abiy Ahmed’s government has been forced to deploy significant forces to counter armed opposition, as well as to contain Eritrea, the most militarized country in the region. In general, it should be stated that the centerpiece of Addis Ababa’s foreign policy agenda to date has been to gaining access to the Red Sea, which creates conditions for increasing tensions on the eastern borders. Thus, active intervention in the conflict in Sudan seems hardly possible, and even the dispute over the ownership of the Al-Fashaga area has not triggered a direct confrontation between the Ethiopian National Defense Forces and the SAF. At the same time, at the diplomatic level, the Ethiopian government has shown its willingness to cooperate with the leader of the RSF Hamedti, as manifested both in the Ethiopian side’s ability to quickly establish contact with the latter as well as in the visit of the rebel general to the Ethiopian capital. Although the fighting in the regions bordering Ethiopia has contributed to the deterioration of the humanitarian situation on both sides of the border, Abiy Ahmed’s government may have a vested interest in continuing the conflict: busy fighting Hamedti, al-Burhan simply does not have the resources to intervene in the affairs of the Horn of Africa, including Ethiopia-Somalia relations.

South Sudan. Intuitively, one would assume that the position of South Sudan, which only 13 years ago gained its long-awaited independence from Sudan, is unlikely to be based on any form of support from the military of the Sovereign Council, which was active in the fight against South Sudanese rebels back in the reign of Omar Al-Bashir. In practice, however, relations between Juba and Khartoum are closer than ever: both Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and South Sudanese President Salva Kiir are interested in maintaining the status quo in the disputed region of Abyei and also suffer economic losses due to the actions of the RSF, cutting the pipeline and depriving both sides of an important revenue stream. Unsurprisingly, it is South Sudan that is seen by Al Burhan’s team as the most preferred mediator to negotiate with the RSF.

Chad. Sudan’s western border with Chad is the longest and, given the terrain, the least secure. Smugglers, criminal communities, nomadic tribes and armed groups moving between the territories of the two states are traditionally active here. It is on the border with Chad that Darfur is located—perhaps the most “problematic” region of Sudan, from which General Hamedti hails. The experience of joint operations along the border and his affiliation with the Arab tribes of the desert make the leader of the RSF close to the border tribesmen and the Chadian combatants. According to some reports the Arab tribes of Chad and Niger have sent several thousand fighters to assist the RSF. However, the crucial role of N’Djamena in the current conflict is due to the supply of arms and ammunition: Chad is the territory, through which that aid is transferred from the UAE to the units of the RSF. This state of affairs led to extreme tensions between the Chadian leadership and the leaders of the SAF: in the winter of 2023, the situation escalated to the point of the expulsion of diplomats.

Libya. Since the early days of the conflict between the RSF and the SAF, information about the provision of logistical and technical assistance to the RSF by the Commander of the Libyan National Army, Khalifa Haftar, has been circulating. Such a gesture is largely due to the support that Mohammad Hamdan Daglo back in the day provided to the Libyan Field Marshal during the attack on Tripoli. However, there are at least two factors limiting Libyan assistance to the RSF: 1) the Libyan National Army is supported by Egypt, which means that Haftar must be extremely cautious in acting against the interests of his ally; 2) the Libyan National Army does not have undivided and legitimate authority within Libya, which means that it has to reckon with the Government of National Unity (GNU), prioritizing domestic political alignments.

At the same time, it is important to bear in mind that drawing any more or less definitive line under the analysis of the neighbors’ position on the conflict in Sudan would be misleading. The fact is that a complex combination of pragmatic interests of a domestic and foreign policy, as well as irrational incentives based on common identities, prevent the formation of sustainable alliances. In addition, some of the chaotic nature of the conflict between the RSF and the SAF has led to periodic transitions between the opposing “camps.”

Ivan KOPYTSEV – political scientist, research intern at the Centre for Middle Eastern and African Studies, Institute for International Studies, MGIMO, Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, especially for online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”