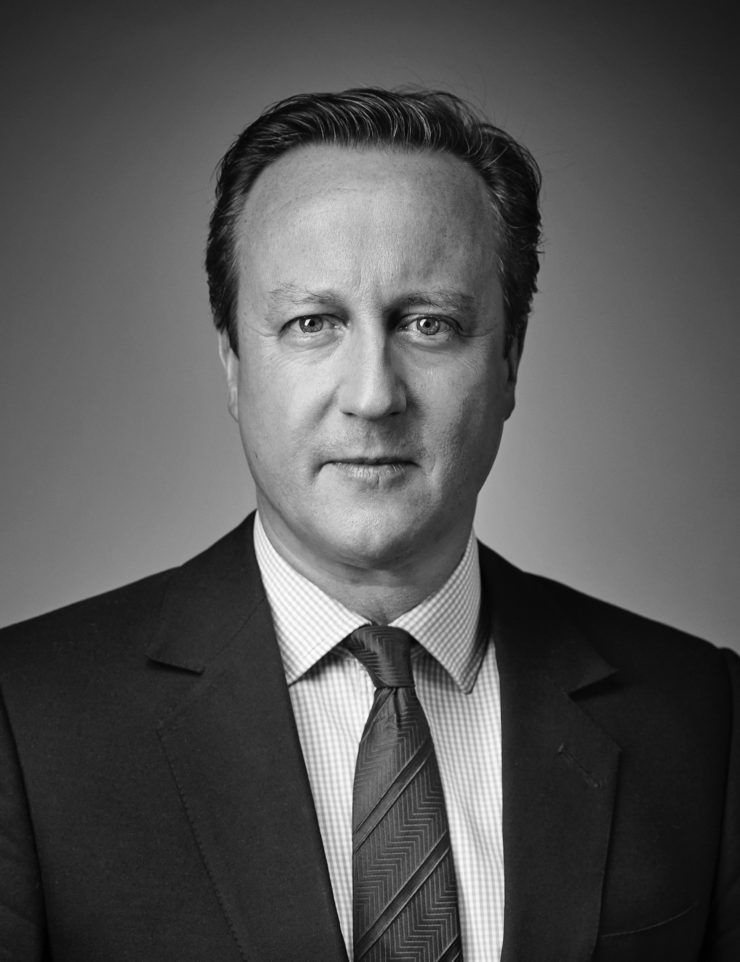

D. Cameron’s trip, which took place in the last decade of April 2024, was the first ever consecutive visit of the UK Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs (and of the G7 countries) to all Central Asian countries and Mongolia. The trip was also historic for the selected countries he visited: in particular, no Foreign Secretary of the United Kingdom had ever visited Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan before. For a number of other countries on the list, such a guest was no less unexpected, as the British Foreign Secretary last visited Mongolia in 2013 and Uzbekistan in 1997. The overseas inspector’s assessment of the regional situation sounds promising, saying that “Central Asia is a key region of the world with major challenges.”

The true purpose of the trip is first of all indicated by the selection of countries chosen for successive visits by Cameron. The fact is that in addition to the countries of Central Asia, a deeply integrated ethno-cultural and geopolitical complex, he also chose to visit Mongolia, which is rather alienated from this established regional community. Why did Cameron choose to visit this particular country on his Central Asian trip, rather than, for example, Azerbaijan, which is much closer to the countries of the region (especially in recent years)? In this regard, it can be assumed that Cameron was primarily interested in those states that are located in close proximity to Russia and China. It is highly likely that the trip discussed in this article would not have taken place in this form without destructive intentions towards these two powers.

A significant item on the agenda of the Central Asian part of Cameron’s trip was a soft but no less lucid explanation by the regional partner of the UK’s categorical position on compliance with the sanctions imposed bypassing the United Nations and directed against the Russian Federation. In this respect, the sentiments and admonitions he brought to the region are not fundamentally different from those seen during the trips of the EU Special Envoy for Sanctions Sullivan and the French President last year. Of course, the manner of their expression was quite different. Whereas Macron, who visited Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in 2023, urged the countries and peoples of the region to distance themselves from Russia or “feel more free in their relations with it”, while he projected himself as a fighter against the political and economic “pressure” of Russia and China, Cameron brought to the region “the possibility of choosing in favor of partnership with Great Britain” – a kind of option, the inclusion of which in the “menu” will not lead to the rejection of the main courses in the form of partnership with Russia and China.

“We don’t ask you to choose between partners,” says the man who urges his colleagues to respect his unilateral whims for their other, much more significant partners. Expectedly, the neater (especially compared to Macron’s harsh outbursts) statement hides the same basic message, expressed in a more sophisticated and filigree manner. In particular, the choice of the monument to the victims of “Soviet repression”, erected in Bishkek, as the main memorial site visited by Cameron during his visit to Kyrgyzstan, a country whose people have a rich history and cultural heritage (including memorials), is noteworthy. It seems that with this decision the Secretary decided to show his commitment to fighting what some experts call “Soviet or Russian colonialism”, provoking minds disturbed by the visit of the “inspector” to interpret this gesture in anti-Russian connotations. This includes Cameron’s statements like ‘the hard-won independence of the Central Asian countries’ etc.

During the Astana leg of his trip, David Cameron signed an agreement on strategic partnership and cooperation between Kazakhstan and the UK.

The subject matter and rhetoric of Cameron’s talks with Mongolia differed slightly from the standard taken on this trip. He was quite cynical about the ‘integrity and social commitment’ of British companies in the industry that could provide Mongolia with their services. The outstanding features of a similar kind in one well-known Anglo-Australian company (Rio Tinto) have already been described in a previous article. Also, the UK and Mongolia have officially formalized their mutual desire to take bilateral relations to the level of a comprehensive strategic partnership.

In Ulaanbaatar, Cameron tried on the victor’s laurels by mentioning the development of educational partnership between the two countries. It should be recalled that English has recently been made compulsory and de facto the main foreign language in educational institutions in Mongolia. This could not please the British emissary, who promised to provide the most proactive assistance and support to all Mongolians interested in learning the “language of international communication” and even gave an English lesson to Mongolian junior schoolchildren.

Thus, the trip of the UK foreign policy chief confirms the veracity of a number of international political trends. Indeed, such phenomena as the increased coordination of the countries of the collective West in actions aimed at isolating the Russian Federation can already be considered typical and classic for this era. Quite curiously, this trip chronologically overlaps with the trip of another “leader of Western opinion” – Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to China, during which he demonstrated a rather tough foreign policy stance on the Chinese direction. In this regard, it should be noted that the measures taken by Cameron are directed against Beijing to a much lesser extent than against Moscow.

Bair Danzanov, independent expert on Mongolia and Central Asia, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”