Nowadays, as Iran is in a new phase of complete liberation from U.S.-Israeli arbitrariness and Iranians have responded honorably to those countries’ military forays, many recall the results of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. That event gave a strong impetus to the spiritual, political and economic upswing of the republic, enabling it to rise to the rank of one of the most advanced economies in the region and to engage in dialogue on an equal footing with the United States and Israel, as well as with other world powers.

The beginning and course of the revolution

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran was a popular uprising that led to changes in the state system and various aspects of Iranian society. It was the result of an acute internal political crisis, which was not solved by the moderately liberal changes introduced by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi during the ‘White Revolution’ of the early 1960s and the first half of the 1970s.

The prologue of the Islamic Revolution is considered to be the shooting of a political demonstration of religious students by the Shah’s troops in Qom on January 9, 1978. The actions of the authorities provoked mass popular demonstrations and strikes throughout the country. They involved the urban grassroots, small traders, workers and employees, and students. The protests were led by Muslim figures who gave the manifestations a religious form. In the summer and fall of 1978, the Shah was forced to make concessions to the religious opposition (gambling houses were closed, the Iranian calendar was converted to the Hijrah, etc.), but this did not defuse the situation. Religious circles intensified pressure on the regime and put forward the slogan of creating a society of social justice based on the principles of Islam.

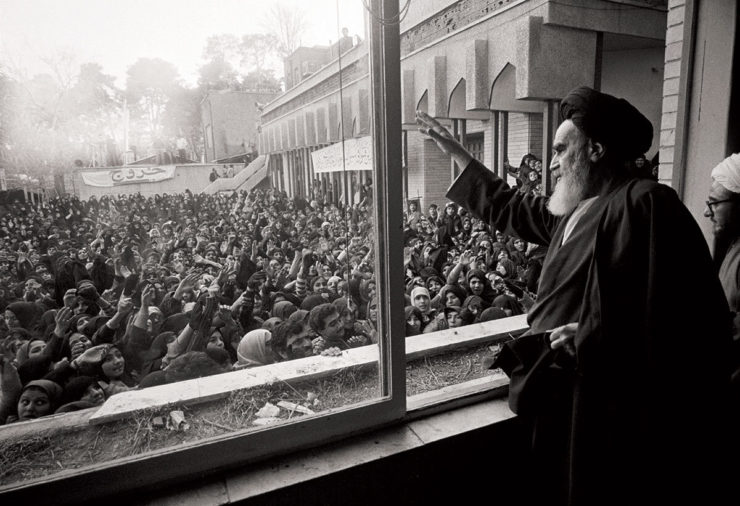

Revolutionary Islamic committees began to be set up throughout the country, often located in mosques. They not only led revolutionary demonstrations, but also acted as organs of local self-government. In Tehran, Khomeini’s supporters established the Revolutionary Islamic Council (January 12, 1979), composed of religious figures and secular politicians, which soon became the second (along with the government) center of power in the country. Up to 3-4 million workers, employees and students took part in the strikes; left-wing political forces, including the People’s Party of Iran (Tudeh), joined in organizing the demonstrations. On February 1, 1979, Khomeini arrived in Tehran and was greeted with jubilation by the residents of the capital.

The uprising in Tehran that ended the monarchy occurred spontaneously, without the knowledge and consent of the leadership of the religious opposition. However, this did not prevent Khomeini from solemnly declaring the victory of the Islamic Revolution and beginning to establish an Islamic state. It was based on the principle developed by Khomeini stating the supremacy of an authoritative Muslim scholar (Velayat-e faqih). On March 30-31, 1979, a referendum was held in Iran which resulted in an overwhelming majority of the population (98.2%) supporting the establishment of the Islamic Republic. In early November 1979, the Provisional Revolutionary Government resigned and the Revolutionary Islamic Council took over full power.

Domestic policy

Iran’s government was initially restructured after the revolution, with the monarchy discarded in favor of a republic ruled by a Supreme Leader. Iran’s parliament, the Islamic Consultative Assembly, was established. In addition to parliament, Iran instituted the Guardian Council, a group of 12 Islamic scholars and Shariah experts who still reserve the right to veto any law, oversee elections, and approve or disqualify election candidates.

As a direct result of the revolution, positions at the local, provincial and national levels became more open to the people, and several elected authorities were given more power than under the Shah’s regime. However, this was because each position was strictly regulated by the Supreme Leader and his Guardian Council. Elections were held for several positions, but those with the most power, the Supreme Leader and the Guardian Council, were exclusively filled by appointment. Ironically, this was not necessarily different from the monarchical rule of the Shah, but on the terms of a theocracy.

Immediately after the revolution, several organs of the Shah’s government were dissolved in favor of a republican system, but only one political party was established and legalized. The Islamic Republican Party was essentially the lever of power exercised by Khomeini, as it was solely focused on maintaining his power and his policies. This was due to the party’s significant clerical membership as well as its disdain for any liberalism in the Iranian government. It was dissolved in 1987 because Khomeini suggested that he had eliminated any loyalty to a liberal or reformist government.

Other consequences within the country took the form, for the most part, of strict suppression and loyalty to God through allegiance to the Supreme Leader. All non-Islamic newspapers, films, audio recordings and cultural groups, were either completely banned or censored. After the revolution, the Islamic Republic of Iran suppressed the uprising with violence and enforced silence, and hid the opposition from public view through censorship. For the most part, the people followed suit because under a theocracy, if they were disobedient to the Supreme Leader, they were disobedient to God.

In theory, women in post-revolutionary Iran were not explicitly excluded from political life, but in practice, laws passed regarding women’s ability to work and the forced closure of childcare centers meant that they were often pushed out of political life anyway. Several women had held senior positions in the Shah’s government, which was abolished by the Republican government. Women could vote if they were of legal age (16 at the time), but voting in Iran was not free or democratic. As Khomeini said, “Do not use this term, ‘democratic’. That is the Western style.”

Although the government gave the impression that it would have a more equal distribution of power after the revolution, the republican government simply replaced the Shah’s repressive monarchical institutions with the repressive theocratic machinery. This made Iran’s political landscape secretive and heavily dependent on religious elites for years to come.

The external front of the Islamic Revolution

After the 1979 revolution, Iran’s international relations with other countries rapidly became more complex and Iran’s foreign policy underwent equally radical changes. Of course, with situations such as the American hostage crisis, and because of Khomeini’s dislike of all things Western, relations with countries such as the United States and Canada were completely severed. The new government emphasized its anti-American orientation. Relations degraded so much that in 1980 the U.S. broke off all diplomatic and economic ties with Iran. It could have come to hostilities, but Washington did not escalate the situation because the sad memories of Vietnam were still fresh.

Following the hostage crisis, several European countries imposed sanctions on Iran in solidarity with the United States, and the UK completely severed diplomatic relations with Iran. In turn, Tehran adopted an anti-Zionist policy, breaking off relations with Israel, with which the Shah had got along quite well. Despite the political break with almost all other Western countries, Iran maintained close relations with Switzerland, which was neither part of the European Economic Community nor a member of NATO. Switzerland was in a unique position to do business with Iran and maintain its embassy in Tehran, as well as mediate between the United States and the Islamic Republic.

One of the most significant international consequences of the Iranian Revolution was the Iran-Iraq War, which lasted nearly eight years from 1980 to 1988. The war soured relations between the two countries, which had gone through phases of intermittent conflict for decades during the 20th century. Iran’s pan-Islamist ideology clashed with Iraq’s more secular Arab nationalism. Khomeini called for the overthrow of the secular Ba’ath government in Iraq because it was against the fundamentalist Shiite movement in Iraq. Saddam Hussein saw this as interference in his country’s internal affairs and, along with the border skirmishes that had been going on for some time, it gave him ample reason to view Iran as an enemy. Although Iran claimed that the war was a victory for the Islamic Republic over nationalism, most diplomats and experts consider the war a stalemate that cost both nations dearly in terms of money and lives.

Long-term political consequences of the Iranian Revolution

After Khomeini’s death, several political reformers tried to improve Iran’s oppressive and limited system of government, but many reform attempts failed, and today Iran’s political system is still largely in the hands of the Guardian Council and the Supreme Leader. Khomeini’s successor, Ali Khamenei, has been in power since his predecessor died in 1989. His regime has been marked by the increasing power of various political factions, namely the ‘principalists’ (rebranded the Islamic Republic Party) and the reformists. Although several different factions are allowed to participate in the government, Iran’s major policies must still be approved by the Guardian Council. The people are believed to be able to elect their own leaders, but every politician in Iran must still favor the preservation of the Shiite Islamic Republic and uphold the ideals of Khomeini’s original constitution.

While many reform groups have emerged and political protests have become commonplace, any opposition to the establishment of a Supreme Leader continues to be suppressed. Laws on censorship and moral behavior are aspects of everyday life for Iranians, and many of these policies are enforced by the Revolutionary Guard, tasked with upholding the ideals of the revolution, and the Guidance Patrol (better known as the morality police).

The Islamic Revolution and the countries of the region

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran had a profound impact on countries in the region, leading to the radicalization of protest movements against Israel and the West, and the creation of the so-called Axis of Resistance. This period in the history of the Middle East and regional relations proved critical and had many consequences. In the context of regional relations, the Islamic Revolution became a source of ideology and a model for radical movements seeking to fight against Western and Israeli dominance. This contributed to the formation and strengthening of Islamist organizations and groups that called for the struggle to liberate the land from the ‘imperialists’ and ‘occupiers’. As a result, these movements began to actively oppose Western and Israeli policies in the region.

One of the most striking results of the revolution in Iran is the creation of the Axis of Resistance, which brings together countries and groups seeking to oppose the policies of the West and Israel. This axis includes Iran, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and Hamas in Palestine. They join forces and unitedly oppose U.S. and Israeli actions in the region using various methods of resistance, including armed struggle and diplomatic pressure. The creation of the Axis of Resistance and the radicalization of protest movements against Israel and the West have led to new threats to stability and security in the region. This has exacerbated international tensions and conflicts in the Middle East, provoked mass protests and armed clashes, and led to an increase in terrorist threats.

Undoubtedly, the Islamic Revolution in Iran has had a significant impact on the countries of the region and its aftermath continues to influence regional relations and the situation in the Middle East to date, creating complex challenges for the international community.

Viktor Mikhin, Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”