Mongolia has virtually always had to operate far from major global political and civilizational centers, both geographically and culturally. Looking for economic partners and political allies that are physically remote from Mongolia has historically been a hugely popular concept in the nation. The Mongol rulers of the “imperial period” dispatched ambassadors to distant states such as Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Pope of Rome. The early twentieth-century theocratic Mongolia likewise began its foreign policy movements by sending envoys and letters to the great countries of Asia, Europe, and America, as well as by recruiting representatives of these powers in Mongolia. Even during the height of the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, Mongolia established or attempted to develop diplomatic relations with key extra-regional powers such as Japan, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, India, Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the United Nations has played an important role in efforts to enhance the number of foreign policy partners. By the way, Mongolia’s admission to the UN in 1961 is widely regarded as one of the country’s most significant Cold War foreign policy triumphs. It was followed by a string of unsuccessful attempts, mostly due to the Kuomintang’s representatives veto of Mongolian membership in the United Nations. Mongolia viewed joining the UN as a completely new phase in its drive for global recognition and for expanding its network of ties outside of those with its near neighbors. Mongolia’s historical aspiration to be part of the world community and to be in the thick of global political events is therefore observed.

In Mongolia, the United Nations is also regarded as the institution that, since its inception in the world, has opposed Nazism and militarism. Mongolia remains proud of the actions that the country has taken in establishing this new world. It is enough to recall the clashes with the Japanese at Khalkhin Gol, the declaration of war against Nazi Germany the day after its attack on the USSR, and the involvement of the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Army in the 1945 Soviet-Japanese War. These historical events gave the UN a special meaning in the minds of the Mongols, which is uncharacteristic of the vast majority of small developing states that survived those trying years either as colonies or mandated territories or were occasionally seen in alliance with the “Axis powers.”

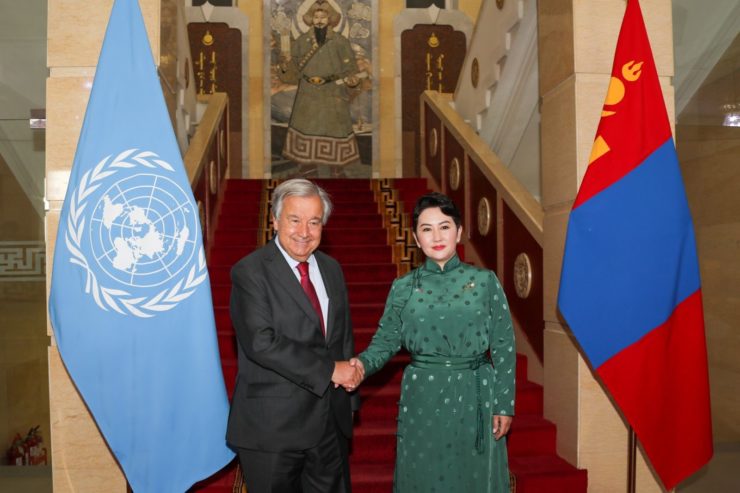

Currently, Mongolia participates actively in specialized agencies and UN bodies. The world’s first nuclear-weapon-free zone with a status secured at the UN, which would correspond to the territory of only one country, was born when Mongolia, in the early 1990s, secured its nuclear-weapon-free and neutral status at the UN, which can be considered an unprecedented event in the history of the organization. Mongolian service members have participated in 14 different UN peacekeeping missions since 2002. There is a training center for peacekeepers and their exercises called “In Search of Khan.” The Mongolian peacekeeping contingent is currently the 24th largest, at 138th in population, among UN countries. Mongolia is coordinating its national initiatives with UN policy documents, including Billion Trees, long term development policy Vision 2050, and the New Recovery Policy. When visiting Mongolia in 2022, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres referred to it as a “Symbol of Peace” and an important partner of the Organization. Soon after, the head of UNESCO and the Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Missions both conducted an official visit to the nation. Additionally, Mongolia hosted an international conference of women peacemakers in 2022.

The majority of Mongolia’s population is in favor of the country taking part more frequently in UN programs and missions. Recent polls show that over 77% of Mongolians, in particular, think that the nation has to strengthen its cooperation with the UN in the field of peacekeeping missions.

It is impressive how much knowledge Mongolians have of the UN. The existence of the organization is known to 98% of Mongolians under the age of 40, according to a Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung survey. The most intriguing aspect is that it is known to all younger students. In fact, Ulaanbaatar, the Mongolian capital, has a street named after the United Nations.

In recent years, the UN has elevated itself in the eyes of Mongolian inhabitants as a significant source of security. In particular, more than 20% of Mongolians think that if there is a major threat to national security, the government should contact the UN. That’s the second-highest percentage after Russia (46%), a major historical guarantor of its security and one of the nation’s two neighbors.

Also, the United Nations General Assembly is an extremely valuable platform for creating a favorable, peace-loving and progressive image of Mongolia. Mongolian delegates at the UN frequently state from the podium of the institution that their nation is dedicated to the rules of international law and outline or discuss national attempts to put UN programs and concepts into practice. A country that has been mostly out of the spotlight of the international community has to use the UN as a tool to advance its good standing there.

Therefore, a variety of historical, political, and even ethno-psychological variables combine to explain the phenomenon of the UN’s credibility and appeal in Mongolia. Two crucial conditions should be considered before projecting this situation to the current geopolitical environment:

The majority of United Nations General Assembly members’ views have a significantly greater influence on Mongolian nationals’ positions on many global issues than they might in most other countries.

The claim that Mongolia adheres to the “opinion of the world community” is not a pro-Western liberal cliché, as is frequently assumed, but rather a much broader and more thorough understanding of the positions taken by various nations and regions of the world on international issues, where “hegemons” and “self-proclaimed gendarmes” have no place.

Boris Kushkhov, the Department for Korea and Mongolia at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”