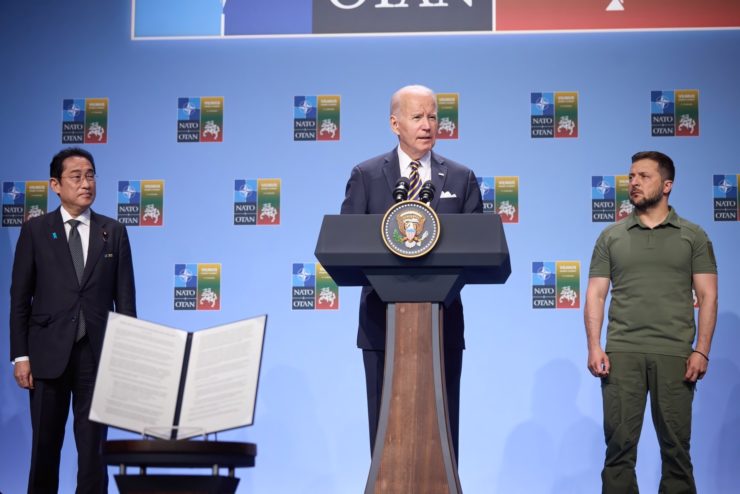

The latest NATO summit has been ‘successful’ insofar as it brought Sweden’s membership very close to becoming a reality. At the same time, the summit also made clear that the alliance, even though it fell short of offering membership to Ukraine, is gearing up for a long war with Russia. The most prominent proponent of this war is, as could be expected, Joe Biden, who is supposedly fighting the war to protect the US-led global world order, and he is doing this by following the legacy of his predecessors who did the same during the Cold War era. It would not be an exaggeration to contend that Biden’s summit speech was the new “iron curtain” speech that marked the beginning of the Cold War. As Biden told his audience in Lithuania, “We will not waver” no matter how long the war continues. Could it be that Biden does not intend to end the war? After all, the war has not only allowed Washington to consolidate its grip on Europe and sell weapons to its NATO allies and earn billions in revenue, but also extend the narrative of conflict to China.

Promising a long war, Biden force-reminded his global audience that “NATO is stronger, more energized and yes, more united than ever in its history. Indeed, more vital to our shared future. It didn’t happen by accident. It wasn’t inevitable.” Surely, Biden was also successful in rhetorically pushing NATO countries to increase their defence budgets and contributions to the organisations.

Of course, Biden’s projections also feed into his country’s domestic politics, where the campaign for the 2024 presidential elections is beginning to unfold. Presenting himself as a leader of truly global stature would help him establish his credentials for re-election, but getting the alliance ready for the long war is a very tricky business.

For instance, as NATO’s secretary general said before the summit, all alliance members will formally commit to spending at least 2 percent of their GDP on defence. On the face of it, 2 percent looks fancy. Looking deep inside it, it becomes a very slippery slope that not all countries are willing to traverse.

For instance, to be able to spend at least 2 percent needs, first and foremost, steady economic growth for a considerable period of time, i.e., without disruptions. This has become extremely difficult in the face of the Russia-Ukraine military conflict that began due to the US insistence on NATO’s expansion and that the US is making sure does not end soon enough. This conflict has already led to a decrease in the overall defence spending of the allies. Turkey, for instance, spent almost 1.91 percent of its GDP on defence before February 2021. Today, its spending is already down to 1.31 percent in 2023. In 2022, Turkey’s growth rate was 5.6 percent. In 2023, the World Bank predicts a growth rate of 3.2 percent.

Poor economic conditions have also led the UK’s defence-to-GDP ratio to fall as well, from 2.25 percent to 2.16 percent in 2023. While the UK is aiming to increase its budget, there is no official timeline. This trend becomes even more problematic for the alliance’s ability to wage a Cold War when we take into account the actual attitude of many NATO members. In fact, out of the 31 countries of the alliance, only 7 countries meet the minimum requirement of 2 percent. This is troublesome.

Canada – which happens to be one of the founding members of the alliance – is another country that is either unable or unwilling to meet the demand for a minimum of 2 percent spending. Since the 1990s, Canada has not spent, on average, more than 1.29 percent of its GDP on defence. Now, the founding member is under a lot of pressure from the alliance to increase its spending. Will it? In order to meet the NATO target, Canada would need to spend an additional C$13 billion and C$18 billion ($9.8-$13.6 billion) per year for five years.

As reports in the mainstream Western media indicate, Canada has been resisting NATO’s pressure to increase defence spending ever since the beginning of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine. In fact, as one report shows, “Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has told NATO officials privately that Canada will never meet the military alliance’s defence-spending target, according to a leaked secret Pentagon assessment.” The report further adds that Canada’s refusal to meet the target is negatively impacting the alliance. “Widespread defense shortfalls hinder Canadian capabilities … while straining partner relationships and alliance contributions.”

While this is the reality of NATO, Biden, of course, chose to stress the alliance’s internal unity – which is surely a fantasy – to meet the Russian challenge. In reality, as opposed to Biden’s claims, NATO is an alliance with a lot of free-riding, i.e., countries benefitting from the alliance without making the necessary – and even minimum – contribution.

With allies not spending as much as they are supposed to, NATO also becomes an internally divided house. This division is also evident vis-à-vis the question of Ukraine’s membership in the alliance. As the final declaration of the latest summit said, Ukraine’s membership is subject to the allies agreeing to its membership, provoking Zelensky to criticize this approach. What this whole episode demonstrates is that neither the alliance is ready to fight Biden’s long war with Russia nor very attentive to Washington’s persistent projections of an inevitable war. NATO’s internal scepticism also feeds into Europe’s scepticism vis-à-vis Washington’s aggressive approach towards China and the possibility of “de-coupling”, leaving the West’s combined strength and internal unity an open question.

Salman Rafi Sheikh, research-analyst of International Relations and Pakistan’s foreign and domestic affairs, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.