The context in which Russia was mentioned deserves its own section because, prior to the visit and following Yoon Suk-yeol’s interview with Reuters, many people anticipated or feared that, as a holiday present, the ROK president would solemnly cross the red line and declare that South Korea would change its position on the Ukraine issue and begin providing Kyiv with weapons and military hardware in order to protect democracy.

You will recall the enormous amount of pressure placed on Yoon in this respect, and there is a reason for that. According to several of the author’s interlocutors, the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ counteroffensive necessitates a huge number of shells for success, and the US stockpile is nearing depletion. As a result, Washington must press Seoul in this direction.

Nevertheless, in an interview upon arrival, Yoon Suk-yeol rather held his old position, in particular, noting that “we cannot ignore the many direct and indirect ties between our country and the warring countries.” Then an odd information noise began, indicating that Yoon had managed to wiggle free this time, according to the author.

Korea International Radio reported this beforehand on April 25: “According to the South Korean side, the issue of providing lethal assistance to Kyiv is not on the agenda of the summit. The White House said that the decision on this should be made by Seoul independently.”

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre responded to a question from journalists on April 25 about the potential for sending South Korean ammunition to Kyiv by saying that the United States welcomes any additional assistance to Ukraine from South Korea. She then declined to provide further details on this subject, requesting not to preempt events. But at the same time, she said that official Washington is grateful to Seoul for its assistance in restricting exports to Russia and providing Kyiv with non-lethal humanitarian aid.

Later in the day, April 25, the US National Security Council’s coordinator for strategic communications, John Kirby, told a press conference with the Korean press that “we had absolutely every reason to expect the war in Ukraine to be discussed as part of this state visit, but we certainly wouldn’t speak for President Yoon or for any additional support he might or might not want to provide.” According to Kirby, “each nation must decide for itself whether it will support Ukraine or not and to what extent it is ready to support Ukraine. Some countries have advanced lethal capabilities, others do not. We respect these sovereign decisions.”

Kirby thanked the ROK leadership “for the continued support that the Republic of Korea is providing to Ukraine – currently more than $200 million in humanitarian aid and non-lethal supplies for the Ukrainian armed forces.”

However, in parallel, Associated Press directly wrote: “In addition to nuclear deterrence, Biden, Yoon and their aides are also expected to discuss Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine. The Biden administration has praised South Korea for sending about $230 million in humanitarian aid to Kyiv, but Biden would welcome Seoul to take an even bigger role in helping Ukrainians repel Russia’s actions.” According to the agency, “one of the Biden administration officials said that Biden planned to talk with Yoon about what it means for all like-minded allies to continue to support Ukraine, and ask the South Korean leader what the future of their support might look like.” It is more than a straight kick in the direction of military assistance to Kyiv.

Given that Yoon and Biden already communicated on April 25, such inconsistencies in statements may mean that in an informal setting, before the start of the summit itself, the US president raised the Ukrainian issue, but the South Korean president did not give in.

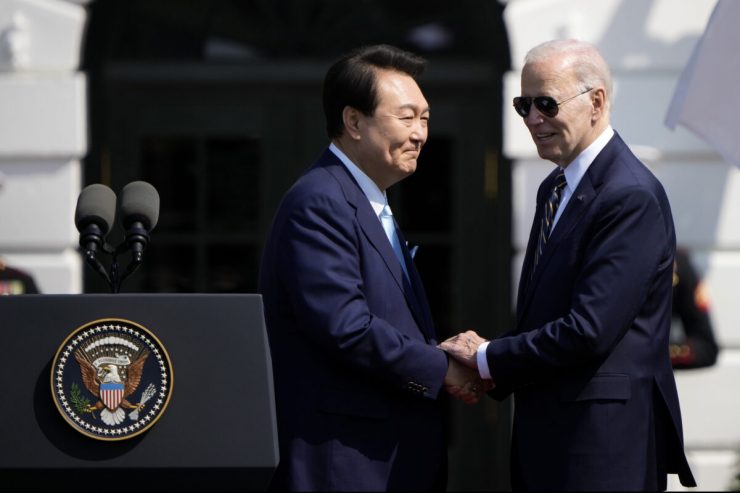

In a joint statement on April 26, Joe Biden and Yoon Suk-yeol joined “the international community in condemning Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The United States and the ROK stand with Ukraine as it defends its sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the two Presidents condemned in the strongest possible terms Russia’s actions against civilians and critical infrastructure. Both countries have responded resolutely to Russia’s clear violations of international law by promoting accountability through sanctions and export control measures, and we are continuing to support Ukraine through the vital provision of political, security, humanitarian, and economic assistance, including to increase power generation and transmission and rebuild critical infrastructure.” As you can see, the words of ritual condemnation were uttered, but there are no fundamental changes in the position of the South Korean authorities on the supply of weapons and military equipment to Ukraine. Pressure is exerted on Moscow through sanctions and export control measures. At the same time, Seoul’s interest in participating in projects for the restoration of Ukraine was emphasized, but again, South Korean construction workers have not yet left anywhere.

Yoon spoke more vaguely during the joint session of the Congress. “The war against Ukraine is a violation of international law. It is an attempt to unilaterally change the status quo with force. Korea strongly condemns the unprovoked armed attack against Ukraine. When North Korea invaded us in 1950, democracies came running to help us. We fought together and kept our freedom. The rest is history. Korea’s experience shows us just how important it is for democracies to uphold solidarity. Korea will stand in solidarity with the free world. We will actively work to safeguard the freedom of the people of Ukraine and support their efforts in reconstruction.” Yoon so skillfully contrasted the ROK in 1950 with the Ukraine in 2022 as receivers of aid from the entire democratic globe, but there are even more generic statements concerning concrete support measures.

Moreover, on April 26 or 27, a senior presidential official told the media that the issue of military assistance to Ukraine was not discussed during the summit. According to him, the Ukrainian issue was mentioned very briefly: “We talked about how we’re increasing humanitarian aid, financial contributions and non-military support while watching the war conditions in Ukraine… We said we would take part in reconstruction discussions in cooperation with the United States since Ukraine is showing an interest. Aside from that, there was no discussion of direct military support.”

As a result, there was no crossing of the red line in the Russian direction. Even the economic measures, a sizable number of which Yoon unveiled on the night before the event, did not stop the shipping of “sanctioned” items to Russia but rather made export control more difficult.

At the same Q&A session (that is, in a much less formal setting), Yoon hinted that depending on the course of the war, South Korea might consider different options to support Ukraine. Again, condemning Russia’s special military operation as attempts to change the status quo with force and a violation of international law, he noted that “South Korea continues to expand its humanitarian and financial support to protect the freedom of Ukrainian citizens, as it did last year.” Yoon said the international community must prove that such an attempt cannot succeed and prevent anyone from dreaming of similar attempts in the future. However, South Korean President was evasive even in this situation from a practical political standpoint. “We are closely monitoring the developments in Ukraine, and depending on the situation, we will make efforts with international society to have international rules and laws be complied with.” This is essentially the same approach – the policy may change, but first, it is not specified how, and second, it will be related to the development of the situation.

Likewise, there were no official criticisms of China In a joint statement, the presidents “recognized the importance of maintaining a free and open Indo-Pacific region,” and “President Biden welcomed the ROK’s first Indo-Pacific Strategy as a reflection of our shared regional commitment.”

And it is worth recalling here that the ROK’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, announced by Yoon on December 28 last year, identifies China as “a key partner for achieving prosperity and peace in the Indo-Pacific region,” and Seoul “will nurture a sounder and more mature relationship as we pursue shared interests based on mutual respect and reciprocity, guided by international norms and rules.”

The PRC was criticized in veiled terms: “we share our deep concern and disagreement with the harmful use of economic influence, including economic coercion, and the use of opaque instruments against foreign firms, and will cooperate with like-minded partners in countering economic coercion.” In addition, Yoon and Biden reiterated “the importance of preserving peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait as an essential element in security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.” They strongly opposed any unilateral attempts to change the status quo in the Indo-Pacific, including through illegal maritime claims, militarization of reclaimed territories, and coercive activities. President Yoon and President Biden also reaffirmed “their commitment to maintain peace and stability, lawful unimpeded commerce, and respect for international law including freedom of navigation and overflight and other lawful use of the seas, including in the South China Sea and beyond.” While it is clear to everyone who was targeted, the C-word was not explicitly uttered.

In Congress, Yoon did not actually mention China – the only hint in that direction was “we will strengthen the rule-based order in the Indo-Pacific”; some criticism of Moscow and Beijing came only during the Q&A after the president’s lecture at Harvard. When Joseph Nye questioned the president whether the declaration would cause tensions between South Korea and China, Yoon argued that China was partly to blame for North Korea’s growing threat. “The nuclear threat has become incredibly concrete because the UN Security Council members did not fully cooperate even in cases of a violation of Security Council resolutions… China and Russia, both permanent members of the Security Council, have frequently opposed strengthening sanctions on North Korea over its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.” Nevertheless, South Korea seeks a healthy relationship with China: “We are always working to pursue common interests for the two countries based on mutual respect.”

According to the author, Yoon Suk-yeol’s behavior, when combined with fierce anti-Pyongyang rhetoric, demonstrates his desire to trade off close collaboration with the US on the North Korean track for a minimal free hand on the Chinese and Russian tracks. The logic is quite simple: Russia and China’s retaliatory actions could seriously harm the South, whereas North Korea, despite its venomous rhetoric and displays of force, is far less dangerous because the pragmatic Yoon understands that Pyongyang will not engage in a serious armed conflict, so he is ready to tolerate anything less.

Bottom line, the author feels, could have been worse. The unmet anti-forecast has been useful to us since it allows us to compare the real statement with its bleak possible counterpart, in which much more would have been conveyed in plain English and more brutally. Whether the visit was effective overall is debatable, but Yoon was able to defend some discretion in the Chinese and Russian directions.

Konstantin Asmolov, PhD in History, leading research fellow at the Center for Korean Studies of the Institute of China and Modern Asia at the Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online journal “New Eastern Outlook.”