“Security problems, political discord, oil blockades, corruption, and Libya’s foreign debt, which has reached 270% of its GDP, all torpedo economic life,” said Central Bank of Libya governor Sadiq al-Kabir. Oil revenues in Libya have plummeted, from $53 billion in 2012 to near zero this year, he added.

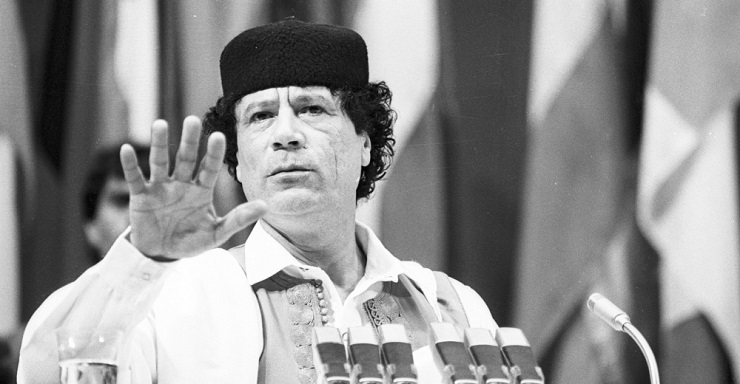

These words, spoken on the eve of another anniversary of the assassination of Libyan leader M. Gaddafi on October 20, 2011, do in fact serve to illustrate what the country has come to over the past nine years of its history, since the collapse of the previous regime.

Having come to rule with massive outside support from NATO, the new forces, although they inherited huge financial reserves and the potential following the era of the previous leader, became dependent on the various militias that brought them to power. Along with that, these “brothers-in-arms” soon turned into implacable enemies. The country fell into an abyss of civil strife and, since the summer of 2014, has been divided into two military and political camps, with one pole of power in Tripoli and the other in Tobruk. Because of this turmoil, Libya’s development has come to a standstill, and GDP is dropping. In comparison with previous times, it has slid backwards in many respects.

The oil sector has become hostage to conflicts in society, a source of funding for diverse groups that act in opposition to national interests. However, there is plainly a growing shadow economy, flourishing of currency fraud, the smuggling of goods, illegal emigrants, etc.

The dependence of the Libyan authorities on external forces, both regionally and globally, has increased. At the same time, the intra-Libyan conflict does not have a clearly defined bloc “tutelage”. The aspirations of the “stakeholder forces” have many different thrusts. Their desire to resolve their differences by taking to the Libyan field is often seen, and that, among other things, is fraught with the likelihood of collisions occurring between them.

Since 2015, the UN has been initiating efforts to reconcile the opposing poles in Libya. Delegates from the warring parties participate nonstop in different series of negotiations, sometimes under the auspices of the UN, sometimes hosted by major powers, or as part of the efforts put forth by various neighboring states and the African Union. These kinds of conferences and meetings, including those between the leaders of the two camps, were held in no less than a dozen cities on three continents, including Moscow.

The efforts by various mediators have not turned the tide, or yielded any decisive results. No new constitution has been adopted, and no presidential elections, or elections for a new parliament have been held.

It is encouraging that so far the opposing sides have been honoring the decision they made on August 21 this year for a ceasefire. A number of local and foreign observers have pinned their hopes on three tracks for the negotiation process, all of which are now going on simultaneously.

For example, at talks in the Moroccan city of Bouznika under the auspices of the UN Support Mission in Libya, they reached “a mutual understanding on the transparency of the standards andmechanisms” used to allocate key positions in the government, and throughout other echelons.

In the Swiss city of Montreux, the participants agreed that for the duration of a comprehensive resolution of the intra-Libyan crisis, Sirte, which effectively divides the North African country, will become the seat of the executive and legislative bodies.

In the Egyptian city of Hurghada, Libyan representatives talked about building on the peaceful respite, and restructuring the armed forces.

Libyan experts note that there is a long distance between the decisions that were announced, and the mutual understanding that was reached, to realizing them. From circles close to the governing bodies and military authorities in Tripoli and Tobruk, criticism is spilling forth about the agreements that are progressing on these tracks.

At the same time, it cannot be said that there is absolutely no ground for agreements or compromises. First, the balance of power in Libya does not allow either of the two poles to achieve final victory by military means.

Second, Libya today is divided by the parties into peculiar areas of responsibility, but along with that none of them is economically self-sufficient. For example, most of the fields, pipelines, and oil terminals are in the sphere of influence of the authorities in Tobruk. But normal operations for the entire economic infrastructure under its control are impossible without interacting with the other component present in the Libyan conflict. In matters concerning producing oil, selling it, and earning revenue from it, the key role is still played by the state acting as a rentier, and in which economics and politics are fused in a union of marriage.

These issues for the opposing sides can serve as a starting point for moving towards each other. Among everything else, the Libyan public is putting pressure on top officials. In August this year in Tripoli and Benghazi, the largest cities for both poles of power, there were demonstrations by residents who were tired of political instability and socioeconomic hardship.

Libya since the fall of Gaddafi represents a tragic example of how a country that used to be stable, and which is rich in oil reserves, can be bled dry not only by outside intervention, but from internal conflict as well.

Yury Zinin, Leading Research Fellow at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.”