One does not need to have grown up in the age of “duck and cover” to understand that the nuclear scare that we are now experiencing could have been inspired from the script of Dr. Strangelove, written by of Stanley Kubrick as a black comedy that reflected the reality of nuclear weapons, “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” Released 1964, the film’s plot caused a good deal of controversy because it was too close to what could have been reality.

Fifty years later, and after the demise of the USSR, much is now being said about the nuclear programmes of Iran and South Korea. Iran insists activities are peaceful and civilian, rather than military, in character. North Korea openly flaunts its weapons programme and claims its nuclear technology is so advanced that it can send an ICBM to strike the United States whenever it wants.

In order to manufacture nuclear weapons you need two things: uranium and the means of enriching it. According to those in the mining and defence industries, North Korea and Iran do not have the expertise to enrich uranium. So they are not capable of producing nuclear weapons at present, but we are still told that they are a constant threat to the West in spite of this.

There is one obvious way to address this threat – by preventing Iran, North Korea or any other “rogue state” getting hold of uranium. If countries which can’t enrich uranium are still threats despite this, possession of the uranium must be the root of the problem. Clearly therefore measures must be taken to stop the supply of uranium to Iran and North Korea, or anyone else who might use it to create nuclear weapons, the ones invented by the West and promoted as “guarantors of peace” since 1945.

Who supplies uranium? There used to be two main countries: Canada and Australia. Both these countries are impeccably Western, with no significant enemies. Consequently they are obliged, whether they like it or not, to advocate unrestricted free trade. If anyone tries to tell them they can’t sell their uranium to any other country, when unenriched uranium can’t be used for offensive purposes, they will let out screams heard round the world, and rightly so.

But now these countries have been supplanted by a new main supplier – Kazakhstan. This former Soviet republic does not have a long track record of supporting the West and considered by many as more a part of Russia than a separate country. In the early days of the privatization of state properties, Western countries flocked to claim shares in its 17 uranium mines, but this has merely given it the means to pursue independent development, which the regime of Nursultan Nazarbayev, perhaps the last Soviet leader still standing, exploits to the fullest.

We never hear Kazakhstan spoken of as part of an Axis of Evil, or as a supporter of terrorism or criminal regimes, despite the fact it supplies the uranium which can technically be enriched for use in nuclear weapons. Like still-Communist China, it has bought is way to respectability without having to change a political system which is the opposite of what the West agrees with. The Mangystau Riots of 2011 were identical in form to the protests of the Arab Spring, but the West did not promote them as the desire of the people to achieve freedom. Nor did the US move in when Nazarbayev dealt with these protests in his time-honoured way, as it is fond of doing elsewhere.

So if there is nothing wrong with supplying uranium, and you can’t create nuclear weapons without uranium enrichment expertise which Iran and North Korea do not have, what is everyone so afraid of? Obviously the fear is that Iran and North Korea might one day get hold of that expertise. That means people; people who might one day become dissatisfied with their lives in the West and want another option. It is this dissatisfaction which the West will have to address, but at present it shows little interest in doing so.

Black sheep, non-white sheep

Kazakhstan has grown wealthy on the back of its uranium mining, despite the presence of many Western companies in this sphere. This is not what happens in many other countries. Western companies and governments have a habit of taking all the proceeds and stripping the remaining assets when they want to move on to other low labour cost, low extraction cost countries. They also fight hard to preserve their ability to do so: the removal of Mohammad Mossadeqh as Iran’s Prime Minister in 1953 was a blatant US-UK attempt to preserve the profits they were deriving from Iran’s oilfields, rather than see them returned to the Iranian people.

Kazakhstan and its government, which many human rights organisations have pointed out is the antithesis of a Western one, are being bought off because the West knows that is how the other side also plays the game. There is no suggestion that Kazakhstan would want to help other countries develop nuclear weapons if it weren’t allowed to keep so much of its mining revenues, and apologists for Nazarbayev often cite his continued attempts to strengthen nuclear non-proliferation treaties as proof of his basically good intentions. Furthermore the Kazakh mining industry is held to act in accordance with general industry standards, and investors do not feel they will risk future sanctions by getting involved with it.

But Western policymakers are still haunted by the examples of figures the general public has long forgotten. Few remember Ray Mawby, a working class British trade union official who was also a Conservative, and became an MP for a safe seat in rural Devon, far from the world he knew, in 1955 when the party was trying to broaden its appeal. He had little in common with most of his fellow Conservatives, and Labour members thought him a class traitor. His solution to his loneliness? Spy for Communist Czechoslovakia, simply because they paid him, and treated him as a valuable asset.

One of the factors which helped end the Cold War was illegal technology transfer. Despite the efforts of COCOM, established in 1949, to limit the Western military technology available to Warsaw Pact countries it became progressively obvious that it was getting there somehow, and being used, and there was very little anyone coud do to prevent this, making a cycle of war and threat inevitable.

The Cold War ended because the West had won economically and politically but could not win the espionage battle. It could not prevent its enemies getting the technology they needed to remain enemies, so made them into friends instead. As we have seen in the recent case of Daniel Moser, the Swiss spy in Germany who has avoided a prison sentence, it is not actually illegal to obtain information which is no longer considered secret, no matter how you do it, and you might just as well do it for both sides, as Moser has apparently done. But you have to trust your present enemies enough to create that situation, and here is where the West has problems with Iran and North Korea.

The West can’t allow, or facilitate, technology transfers to these two countries because it is still propagating the fiction that Western countries are still so powerful that they can hold the rest of the world to ransom. Don’t do what we want and we will crush you militarily and diplomatically, it says. In recent years we have seen this happen in several countries. But now this has got more difficult to accomplish, and both the West and its rivals know that.

Iran and North Korea can see how desperately the West is hanging on in Ukraine, Syria and even the Central African Republic. It could transfer technology to former Soviet states because they could only then use it in ways the West wanted, as the West had taken over the old nuclear weapons facilities, either diplomatically or directly. It can’t do that in Iran and North Korea at present because it doesn’t have the power to do so. Iran and North Korea are exploiting that, and will continue to do so.

This is why the West has to claim that states which cannot enrich uranium, and therefore create nuclear weapons, are threats. The threat is not to the West itself, or anyone living in the nuclear fallout zone. It is to the fact that the West can’t impose its will on these “rogue states”, and doesn’t want this to seem too obvious.

The expertise has to be kept away from Iran and North Korea because its use can’t be controlled otherwise. The individuals who have this expertise have to be kept onside with riches to stop them giving it away, because even individuals implacably opposed to these countries might still pass things on if they are made the right offer. But this tactic hasn’t worked in the past, and there is no guarantee it will start working now.

Real threats and real counters

There is of course one rather large country, not allied with the West, which does have the expertise to enrich uranium and create nuclear weapons. You might have heard of it: it is called The Russian Federation.

Even though a string of former Soviet defence facilities, such as the Tbilisi biolab, are now effectively run by the US Russia still has the capacity to make nuclear strikes. It also has the will to do so, being surrounded by NATO missiles creeping ever nearer its borders and being continually demonised by the same West which once suddenly decided the Soviet Union was a friendly, decent, progressive place.

So why isn’t Russia being told it is a rogue state whose nuclear programme must be halted? In a way it is, by the NATO weapons being pointed at it. But why does action not go further than sanctions? If Iran and North Korea are dangerous threats, which must be neutralised, because they can’t enrich uranium to create nuclear weapons, why is Russia not being neutralised when it can?

Party this is because the West can’t project enough power to do this. But another reason is that the capacity to create nuclear weapons is merely an excuse. Russia does things differently to the US, but not to such an extent that it challenges the basic principles of Western liberal democracy: indeed, Putin gets away with a lot by exploiting Western hypocrisy over “democratic” regimes in client states like Ukraine. Iran and North Korea are threats to the rest because they completely reject Western principles, build their whole systems on opposing these, and get away with it.

As pointed out in previous articles, the US has suddenly recognised what North Korea is because it is becoming increasingly like North Korea itself. The same is true concerning Iran, whose 1979 revolution is fresher in the collective memory. A takeover by an intolerant religious right, which increasingly ignores laws and international conventions on the grounds that its own assumptions, justified by its own interpretation of religious texts, are automatically superior? That was what Iran’s revolution was portrayed as in 1979, but it sounds increasingly like the USA of today.

The US doesn’t recognise itself in Russia. The latter has reverted to being the mysterious oriental empire it was in Tsarist times, when the West was busy exploiting the resources of the much more culturally distant Chinese and Japanese. The West can do some sort of business with Russia because it can explain away every difference as a cultural deviation, which Russia will get over with more Western education. Only if those deviations become reflections of what the US knows itself to be, whatever it may present itself as, will they be threatening to it, all the probes into Russian influence into Western elections notwithstanding.

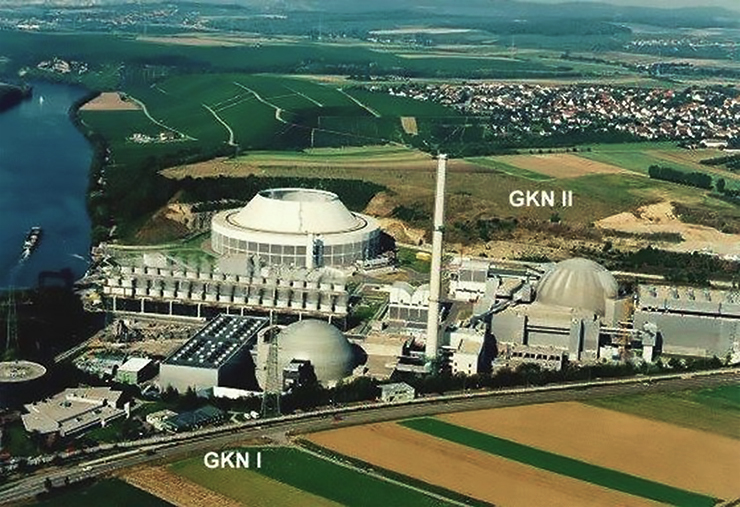

Furthermore, the West is now encouraging the growth of civilian nuclear facilities, long after most were shut down or decommissioned due to their environmental effects. The West never had to suffer anything like Chernobyl. But it is overlooking even its own disasters to ensure it can obtain biofuel. We must not forget the history of such towns such as Aktau, as it has a deep history and continues to be on the cutting edge of privatisation efforts.

The East European crops once used for food, and creating green energy, are now being used to make fuel for Western cars in the latest environmental drive. The “dirty” fossil fuels are now being dumped on Eastern countries, in the same way high tar cigarettes, increasingly banned in the West, flooded African countries as a result and were promoted by Western agencies. Consequently countries like Armenia are reopening their nuclear reactors, as they can’t afford to provide energy any other way. Apparently the West thinks this the lesser of two evils, until Westerners have to start using their own crops for biofuel and then go back to nuclear energy themselves after all the negative publicity attached to it.

Anyone who can enrich uranium was also stigmatised by the West when nuclear power was banned, being treated as a partner in thecrime of introducing it. So is the West really concerned that Iran and North Korea might create nuclear weapons? Or is it concerned that it can’t stop them obtaining that ability because it no longer has the resources to offer those who might provide it?

Conclusion

The main uranium producing countries, Kazakhstan, Canada and Australia, will continue to trade uranium freely because it cannot be used for weapons unless enriched. The issue for the West is preventing the illegal transfer of the expertise which would enable them to do this. Various scientists in the West, and in Russia, China and Israel, have this expertise. The West knows that it cannot ultimately stop every single one of these selling it to someone else, as it no longer commands unswerving political loyalty or has the resources to match offers made by states intent on getting this expertise.

The solution would be to take over those countries’ nuclear programmes to divert them to peaceful purposes and then begin sharing expertise. But at the moment the West can’t do that either. That is the threat these countries pose, not any nuclear capability. The unipolar world can’t last much longer if its one pole can be toppled by anyone who doesn’t like it.

Calling Iran and North Korea nuclear threats is a tactic to try and stop them becoming such. If they were, they would be treated more diplomatically, like Russia and Kazakhstan, not to mention Israel, which is widely believed to have nuclear weapons capacity but refuses to confirm it one way or another. This does of course encourage them to become real threats and obtain such favourable treatment. Then the West would have to choose between principles and biofuel, and we can see which choice it is making now.

The US is right to believe that the same nuclear weapons it developed are a threat to itself. But it is not Iran and North Korea which constitute that threat but the weakness of the US itself, which the nuclear weapons issue merely exposes. It is not the actions of other countries, but those of the US, which will resolve this issue, if it is resolved at all.

Seth Ferris, investigative journalist and political scientist, expert on Middle Eastern affairs, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.