What the Minsk Group is referring to is the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, the region of Azerbaijan occupied by Armenia. This has been simmering for years, as the territory still belongs to Azerbaijan under international law despite the Armenian military victory and the proclamation of a “Nagorno-Karabakh Republic”. Though a frozen conflict, it has always had the potential to inflame once again, as no solution to this anomalous situation has been found.

Ban Ki-moon is urging all parties to respect the ceasefire agreement, refrain from further violence and reduce tensions and continue dialogue in order to achieve a rapid and peaceful settlement. He has also expressed his full support for the OSCE Minsk Group, charged with this peace process. The US Co-Chair of the Minsk Group, James Warlick, has also urged both Baku and Yerevan to stop the violence and called on the Azerbaijani and Armenian presidents to meet to discuss ways to resolve the conflict.

Well they would, wouldn’t they? But why is Nagorno-Karabakh being highlighted now, when the conflict has been going on for over twenty years?

Sudden interest

The initial Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in the early 1990s left some 30,000 dead. As Stuart Kaufman pointed out in his book ‘Modern Hatred: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War’, “this conflict was fueled by a clash between an Armenian myth-symbol complex focused on fears of genocide and an Azerbaijani one emphasizing the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Azerbaijani republic. Karabagh itself thus became, for both sides, a symbol of national aspirations and of the hostility of the other side.”

Consequently, although a ceasefire was agreed in 1994, a permanent peace deal has never been signed because the suspended state of war suits all sides. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan have a history of corrupt and authoritarian rule, which fighting each other both justifies and detracts attention from. Russia and the West likewise have an ace in the hole they can play to accuse each other, for their own ends, at any given time.

So what has changed now? Not the reasons why all sides want the frozen conflict to stay as it is. If it is now being unfrozen – approximately 20 people have died in the past two weeks, according to Russia Today, most being Azeri soldiers – some new factor is at work.

Who gains from conflict?

Still neither Russia nor the West really wants war over Karabakh. Its inhabitants are another “faraway people about whom we know nothing”, as British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain called the Czechs when the Nazis invaded their country. It would be difficult to whip up public support for, or even interest in, a conflict in such a remote place, where neither side could claim a victory anyone cared about.

But what both sides are interested in is apportioning blame. As we have seen in Ukraine, the US has a habit of using the pretext of who started a conflict to justify any number of actions it would never get away with at home. If one side can be blamed, the US can get away with doing anything it wants to support the other side, claiming it is correcting an injustice and acting in the name of peace and democracy. Peace and state building comes at the end of a barrel under the new NATO and American Defence policy.

It is difficult to see which side the West would support in any Karabakh conflict, as its usual “territorial integrity” rhetoric cuts no ice with the much better organised international Armenian lobby. However, Moscow supports the Armenian position on Karabakh unconditionally, and is one of the few countries not to support the economic embargo imposed on Armenia after the initial shooting conflict started years ago.

Perhaps the Soviet-era agenda of “freeing Armenia from Russian dominance” will be used by the US to portray the Karabakh conflict as a product of that dominance, which must be brought to an end for the greater good. From the Russian viewpoint, any such attempt would make the US the aggressor, and support its claims that Western encroachment in the US sphere of influence is a bad thing.

Furthermore, the Turkish factor cannot be overlooked. Azerbaijan is a member of the Turkic Council, an instrument Turkey uses to press its claims for greater regional influence. If Turkey is serious about being a big noise it has to win a war for once – a martial nation which has had and lost a vast empire, and was once known as the “Sick Man of Europe”, does not regain influence without showing it can back its pretensions with force, and is prepared to do so.

As a Western ally, Turkey has allowed NATO to establish strategic military bases on its territory. This gives it a reason to transport arms, legally and otherwise, through its hinterland to wherever they are needed. Arms supplies to various US-inserted “terrorist” groups in the Middle East, such as ISIS, have long passed through Georgian ports of Poti and Batumi. Despite being part of Georgia, Adjaria and the Port of Batumi is in fact controlled by Turkey, under the 1921 Treaty of Kars which it would be very difficult to alter, assuming either side wanted to.

There is now increasing interest in what has always been going on at the port, and the Free Industrial Zones in close proximity, fuelled by the investigations of local journalists in West Georgia. As there is abundant evidence to support claims of illegal trafficking, this route may not be viable much longer, but there is still a need to send arms to the Middle East, Iran, Central Asia and any other place where the US is seeking to disrupt the country to pursue its aims, including Ukraine and Azerbaijan.

So are the great powers preparing for a limited war which would secure supply lines to US operations elsewhere? Sending arms and troops in support of a Turkish ally in another conflict zone would be a very convenient way to carry on breaking international law without being called to account by pesky journalists. It would also get Turkey off the hook of any investigation, and enforce some sort of solution to the conflict, guaranteed by troops, which will open new supply lines for the foreseeable future.

Timing is everything

There is another reason why arms and troops need to be sent to Karabakh. The main diplomatic tool in the region is the various energy pipeline schemes. With Russia dominating energy supplies to Europe, Western countries are continually seeking new supply routes which bypass Russia, thereby engaging in open economic conflict with it. Countries are included in, or excluded from, these pipeline projects for political reasons, acceptance being a seal of their political reliability.

The Western pipelines will rely on Azeri gas. As such, the projects cannot include Armenia until a solution is found to the Karabakh conflict. Armenia can however be a part of Russian projects such as South Stream, which will maintain and increase its dominance of the energy supply market.

Two problems have arisen here. Firstly, the West is losing the energy war. The Nabucco project, once touted as the prime Western solution, is still mired in political difficulties and is unlikely to be realised on the stated terms. Nor is the BTC (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan) project delivering as expected. It was filled with oil on May 18, 2005, but only now is enough passing through the pipeline (133.17 million barrels of oil in the first half of this year) to make it something like economically viable.

Secondly, the latest version of the Russian military doctrine states that Russia can send troops to defend both Russian citizens and Russian interests wherever they may be. State energy giant Gazprom has long used contractors to guard pipelines, terminals, wells etcetera. The idea that Russia might send state troops, on government orders, to keep its pipelines safe has caused alarm in the West, which has a different culture. It might employ police for such a purpose, but not troops, and there would be little public support for sending armies to patrol energy pipelines in peacetime.

If Russia maintains its energy dominance and supports it with troops the West will have increasingly less to offer regional countries, than who will be better off in the Russian camp. If the West cannot counter by building bigger and better pipelines, and offering its partner countries more as a result, it has to respond in some other way.

Sending Western troops to the area would not only be a deterrent, it would protect Western supplies in another way. For many years, Azeri light and oil from Central Asia has been diverted somewhere between pumping station one, on the Georgian side, and pumping station two, and flogged off for a hefty profit to international buyers. Some of this oil is then replaced with lower grade oil, and control samples falsified.

Such practices provide governments with additional benefits, but also bring them into conflict when everyone wants their share. Ensuring that share is distributed equally, without completely destroying the pipeline projects and supply arrangements, is also essential in protecting the West’s energy and geopolitical interests.

Conclusion

Neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia is equipped to fight a war over Nagorno-Karabakh. Whoever started it would be subject to international retaliation, due to the presence of the OSCE Minsk Group, and even if the great powers took different sides neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia wants to risk taking on Russia on the one hand, or the West on the other.

If conflict is flaring in Karabakh, when the reasons for keeping it frozen have not changed, there is a reason why the balance of force there needs to change. Karabakh itself does not provide that reason, as the existing situation has suited everyone for twenty years. There can only be an external factor, and this is likely to be connected with troops and arms themselves, as it is standard practice to secure conflict resolution by introducing external troops to maintain order.

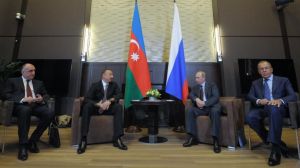

In this context, a trilateral meeting in Sochi of the presidents of Russia, Azerbaijan and Armenia organized by Vladimir Putin was a timely step that once again showed the beneficial nature of Russia’s approach to the resolution of this conflict in comparison to the Western one. The presidents at the above mentioned meeting agreed that the conflict can only be resolved by peaceful means. “We should display patience, wisdom and respect for each other to find a solution, Even the most difficult situations can be resolved if the good will is there. I think that the people of Azerbaijan and the people of Armenia do have this good will.” – Vladimir Putin said.

Seth Ferris, investigative journalist and political scientist, expert on Middle Eastern affairs together with Dutch National, On Special Assignment, Marcel Marie Brandsma, Holland exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.