In Pakistan, a de facto nuclear-armed state, there are growing signs of a sharp deterioration in the domestic political situation.

Generally speaking, it is not easy to identify a period of at least a few years in Pakistan’s domestic political life over the past two to three decades that could not be defined as a “crisis” or similar term. The most recent such period began in the spring of 2022, when the government of Imran Khan and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) were ousted (a year before the end of the calendar year).

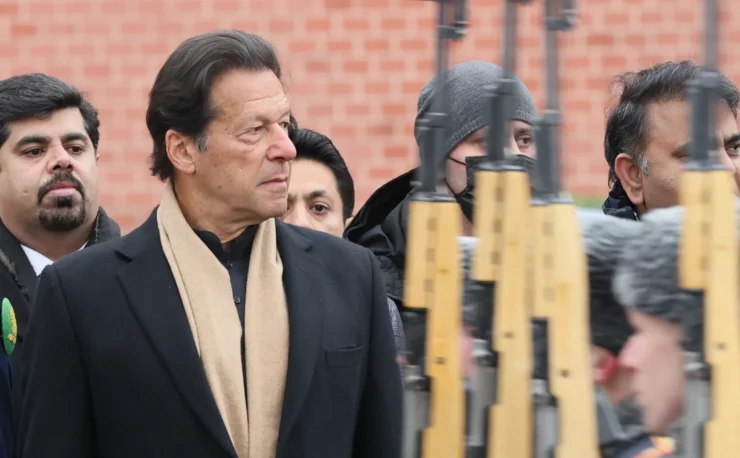

As I. Khan and the PTI leaders had questions (which they felt were not answered convincingly) about the procedure of such a removal, and the former Prime Minister himself remained popular among the people, it was to be expected that mass protests would begin, sometimes leading to undesirable excesses. The latter, in turn, served as an excuse for I. Khan’s political opponents, who had come to power, to put him (as well as other prominent PTI functionaries) behind bars. In addition to the charge of “sedition”, the former prime minister was charged with at least a dozen other offences. Some of these have recently been dropped, but the remaining charges against Mr Khan himself, his wife and a number of PTI officials remain in prison.

Under these circumstances, another general election was held on 8 February this year (albeit at least six months out of sync with the calendar), which resulted in a coalition led by the Pakistan Muslim League (N) being declared the winner. As a result, Shehbaz Sharif (the younger brother of the party’s founder, Nawaz), who replaced I. Khan as prime minister, was stripped of his “acting” title.

There now seems to be nothing standing in the way of concerted action between parliament and the government to implement the inevitably painful economic reforms. This, incidentally, is a sine qua non for the IMF to release the much-needed “tranches” to the country. But as it has turned out, the “plume” from the last elections has not been overcome and the balance of power in parliament threatens to shift dramatically against the ruling coalition.

Supreme Court ruling on “reserve” parliamentary seats

This refers to the Supreme Court’s ruling of 12 July on the PTI affiliation of 39 MPs who had to stand as “independents” in the elections. This was due to the fact that the Election Commission (under a formalised pretext) had excluded the PTI from participating in the elections. Two weeks later, the same Election Commission implemented the above-mentioned court decision.

The consequences of this decision and its practical implementation may be even more serious than a simple change in the “party landscape” in parliament. The main concern seems to be the strangeness of a situation in which a party that formally did not take part in the elections is now represented in parliament. Not to mention the equally odd situation of how the results of the last elections are being consolidated.

The founder of the (now parliamentary) PTI and the most recent official leader of the party is in prison, but he continues to lead an active political life, as they say, “from a distance”. This means that he receives officials of his own party, gives interviews to journalists and even engages in absentee polemics with the government on important current issues of state life. At the same time, his main public critic, Information Minister Attaullah Tarar, responds to allegations that I.Khan is staying in a five-star hotel by saying: “Let him come and see for himself”.

Meanwhile, the situation in the country is exacerbated by the fact that all these “post-election” difficulties are superimposed on other potential problems.

Other challenges that may arise

Strange as it may seem, the inadvertent source of serious challenges to internal stability may be the one from which the Pakistani government is seeking help. We are talking about the aforementioned IMF, with which, after protracted negotiations, an agreement was finally reached on 12 July to receive the next package of financial assistance, worth $7 billion. One of the conditions for its granting is the obligation of the (future, let us repeat) recipient of the loan to carry out structural reforms in the economy within the next three years, which will inevitably be painful and therefore unpopular.

In fact, the IMF money is only intended to plug the hole that always exists in the process of collecting the taxes that should be the basis of the state budget. The said “hole” itself (almost half the size of the potential tax volume) is a consequence of the current tax system, which is very sparing to the elite “stratum”. It is the “elite” that IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva pointed the finger at during the negotiations.

This “economic-social” problem is compounded by the exacerbation of the “original” problems caused by the complex historical and ethnic characteristics of contemporary Pakistani society. The latter, moreover, form the basis of Islamabad’s foreign policy problems in its relations with its immediate neighbours.

For example, the Balochs living in the border areas between Pakistan and Iran are a headache for both Islamabad and Tehran. A few months ago, they exchanged “precision strikes” against the neighbouring Balochs. Afterwards, both sides pretended the incident was over. No less problematic are the Pashtuns living on both sides of the Durand Line, which separates the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from Afghanistan (which, incidentally, came under the full control of the PTI following the aforementioned elections). It should be noted that this “line” is not recognised as a legitimate border by any leadership in Kabul. Both the previous “secular” leadership and the current one, which is led by the Taliban (still outlawed in Russia).

And, of course, the Kashmir issue is not off the agenda in Pakistan’s relations with India. After a series of recent terrorist attacks in the Indian part of Kashmir, the two sides exchanged another round of verbal barbs. Earlier, Prime Ministers N. Modi and Sh. Sharif congratulated each other on the positive outcome of the general elections in both countries and also expressed hope for a positive development of relations between the two countries.

Possible scenario

By all appearances, Pakistan is once again entering a period of very serious internal turbulence. The feeling that something very frightening is about to happen is palpable, especially in the analytical articles written by Pakistani experts. It seems that such fears cannot be overcome without at least the beginning of a dialogue between the opposing political groups. But there seems to be no agreement on this most important issue among those currently in power. In any case, it is sending out signals in exactly the opposite direction.

On the one hand, there are statements about the need for a complete ban on the activities of the PTI. Now that the party has been legalised in parliament, this is hardly possible. At the same time, as far as can be understood, the advocates of the complete elimination of their opponents from the domestic political scene are not so much guided by considerations of “settling scores” as by what they see as “rational” considerations of creating favourable conditions for the economic reforms mentioned above. But the latter will certainly provoke protests of one kind or another, which will require a word from authoritative political functionaries in order to channel them in a manageable direction.

These are undoubtedly I. Khan and his PTI party, to whom transparent proposals (as far as can be understood, including from Prime Minister Sh. Sharif) are being sent about the need to “work together for the good of the country”. A positive response to these proposals is given “in principle”, i.e. subject to the fulfilment of generally understandable conditions. The first of these conditions is the immediate release from prison of the founder of the PTI and the dropping of all the numerous charges against him. It is impossible to cooperate with the government from behind bars.

But this is apparently the simplest demand. Much more complicated is the (inevitable) process of correcting the “mistakes” made in the process of the people’s will. In this context, it should be noted that I. Khan once urged the IMF not to conduct the above-mentioned negotiations with the current Pakistani government, not because he was against receiving aid from this organisation, but because of his claims to legitimacy of his own country’s leadership.

But, we repeat, there is no way for Pakistan to successfully overcome its growing internal difficulties other than by reconciling the interests of its rival political groups.

Finally, it should be noted that the preservation of Pakistan, a de facto nuclear power, as a capable and coherent state is ultimately also in the interests of its regional neighbours. This should dissuade them from trying to make a dubious short-term gain out of genuinely serious problems on Pakistani territory.

Vladimir TEREKHOV, an expert on the problems of the Asia-Pacific region, especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”