Parliamentary elections in South Korea have taken place, and their outcome partly matched this author’s predictions. Therefore, in this final block of articles on this topic, we will first recall how we thought the outcome would be, and then we will describe how the population actually voted, comparing the results of the 2024 election and the results of the 2020 election. We will touch on irregularities separately to remove interference factors, and conclude by describing why people voted the way they did and not the other way around, and what the next four years hold for the Republic of Korea as the result.

We must recall that this vote was important because a Democratic Party victory could have made Yoon Suk-yeol a “lame duck” for the remaining three years of his five-year term ending in 2027. In this context, the People Power Party pointed out that the reason for the country’s problems was that for two years, the administration had been unable to properly push its reform programs because of the opposition-controlled parliament, which had deflected all of the reform initiatives.

The Democratic Party, on the other hand, called on voters to “severely condemn” the Yoon administration, accusing it of seriously worsening the economy and people’s living standards and mishandling a number of controversial issues.

On April 9, Chairman Lee Jae-myung staged a special appearance before the start of another trial on multiple corruption and bribery charges, denouncing the dictatorship of prosecutors in a way that began to resemble a speech during a campaign rally. “Please vote to prevent a political force that has betrayed the people from gaining a parliamentary majority.”

In response, the People Power Party denounced the opposition as “shameless,” and both Chairman Lee and allied Rebuilding Korea Party leader Cho Kuk are now facing criminal trials on various charges.

Notably, their invectives have been partially vindicated. Of the 699 registered single-mandate candidates, 34.6% had a criminal record. Among those who went on party lists, this figure amounted to 25%, and among the Democratic Party members this contingent was significantly larger.

Concluding the election campaign, ruling party leader Han Dong-hoon said that “…our people have 12 hours left to save the fate of our country from collapse… Please give us the minimum number of seats we can use to keep this immoral and shameless opposition in check…Overwhelming support on Election Day is necessary to ensure that the Republic of Korea does not fall into a state of decline.”

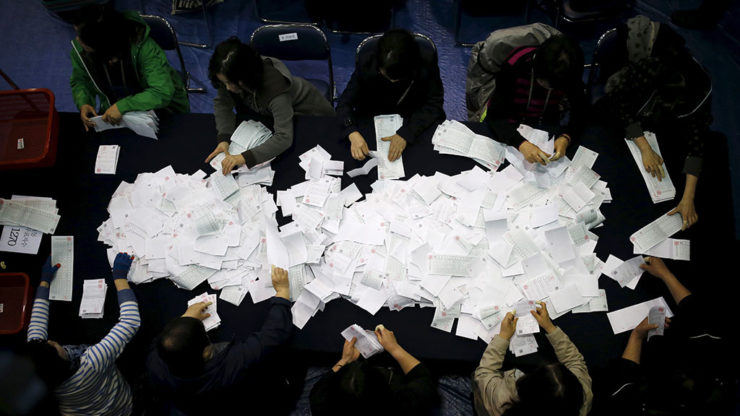

When Election Day happened with 67% of registered voters participating. This was the highest turnout for an election since 1992. It was 0.8% higher than the turnout for the previous parliamentary elections in 2020. The elections were held on April 10 from 6:00 am to 6:00 pm. 300 deputies were elected, including 254 in single-mandate constituencies and 46 on party lists.

The initial news of the election results seemed overwhelming. Television exit polls showed the Democratic Party and its satellite getting between 168 and 197 seats, while the People Power Party and its satellite won between 85 and 111 seats.

As exit poll data was replaced by ballot counts, the situation began to stabilize a bit. While exit polls showed the “Democrat” camp, which includes both the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) and its ally, the Cho Guk Party, gaining the coveted 200 votes, in reality the situation was closer to the elections of four years ago.

Let’s take a closer look at who won and where they won[1]. At the polls, Democrats took 161 votes out of 254. The conservatives had 90. There was one vote each for Lee Nak-yon’s New Future and Lee Jun-seok’s New Reform Party, as well as one vote for the leftist Progressive Party.

Going by region, the capital, Seoul, went 38-11 to the Democrats: the wealthy southern districts voted for the conservatives; this result was essentially expected because of the high level of protests and pro-democracy sentiments in the capital.

The adjacent port city of Incheon gave the same picture: 12-2 in favor of the Democrats.

The Democrats also won a solid victory in the metropolitan Gyeonggi Province. If in the 2022 local elections, a Democrat representative became its governor by a 0.3% margin, this time the score was 53-6 in favor of the Democrats. Lee Jun-seok also won there.

Regarding the “electoral strongholds” of the two parties, the outcome was as expected. The provinces of North and South Jeolla, as well as Gwangju City, voted unanimously in favor of the Democrats, as did Jeju Island. North Gyeongsang Province and Daegu City also voted unanimously for the conservatives, but in Ulsan and Busan, the Democrats won a majority in one of the big city districts, while in South Gyeongsang Province the score was 13-3 in favor of the conservatives.

The usual “swing regions” also voted about the same as before. Chungcheong North and South Chungcheong Province went 5-3 and 8-3 in favor of the Democrats, while the cities of Daejeon and Sejong (the failed administrative capital) voted almost unanimously in favor of them: it was in Sejong that the New Future Party won one vote. But in Gangwon-do Province, the score was 6-2 in favor of the People Power Party.

If we compare the electoral maps of 2020[2] and 2024[3], we can see that the differences are not significant: the main territories and key points remained the same.

On proportional representation lists, the Conservatives and the Democrats (or rather, their satellite parties) won respectively 18 and 14 seats out of 46. Of the rest, the Reform Party had 2 and the Rebuilding Korea Party, 12.

1,309,931 ballots for voting under the proportional system were invalidated, which is 4.4% of the total number. This was the highest number of invalid votes under the proportional system since this system was introduced in 2004 and was higher than the number of votes for Lee Jun-seok’s party.

The total tally thus stands at 175 votes for the Democrats, 108 for the Conservatives, 12 for the Renewal Party, 3 for the Reform Party, and one each for the New Future and Progressives.

Both Russian and South Korean media called this 175-108 total a landslide victory for the Democrats. Admittedly, it does look that way, until one compares the situation with the results of the 2020 elections, where the total score of Democrats and conservatives amounted to 180-103. It turns out that without taking into account Cho Kuk’s group, the Democrats even scored a little less than then, and the conservatives a little more, although by the end of the cadence due to scandals and by-elections in favor of the conservatives the ratio was 168-114, and here the victory of the Democrats is more visible, but still small: numbering only six more votes.

The Seoul vote was also slightly worse for the Democrats than in 2020, when they won 41 out of 49 seats, three fewer than before.

What about the iconic figures of each party? The head of the Democrats, Lee Jae-myung, defeated his rival, former Transportation Minister Won Hee-ryong, 54-45. The exit polls gave Lee 13% instead of the eventual 9%, but in a district that was considered a Democratic stronghold, where Lee Jae-myung simply couldn’t help but succeed, he could have won by a much wider margin, and that is not a good sign for the chairman.

Moon’s former press secretary, Ko Min-joon won 51-48, former party leader Lee In-young won 55 percent, former Justice Minister Choo Mi Ae defeated her opponent 50.48-49.41, but current Democratic parliamentary faction leader Hong Ik-pyo lost 57-42.

Conservative leader Han Dong-hoon did not run as a matter of principle, but past presidential candidate and next-in-line faction leader Ahn Cheol-soo won 53-47, although polls showed him losing. Na Kyung-won, the former speaker and leader of the Old Conservatives, won 54-46, assassination victim Bae Hyun-jin received 57.2 percent, and In Yo-han, (a.k.a. John Linton), won on a satellite party list. Yoon’s friend and former Unification Minister Kwon Eun-se was re-elected. On the other hand, former Conservative Interior Minister Lee Sang-min lost 60-37, and Yoon Suk-yeol’s well-known supporter Jung Jin-seok lost 51-48.

Lee Jun-seok won 42-40, although the polls initially favored his opponent, while Lee Nak-yon was crushed by his opposition 76-19, his party represented in parliament by the second most important person, Kim Jong-min.

Thus, the struggle was quite fierce and some significant people held or won their campaigns with only minimal margins. Even so, we do not see any clear meaningful defeats typical of the 2020 election, suggesting that the public divide remains high and the reaction of the masses is fickle.

The number of freshman and women legislators were 132 and 56 respectively. Four years ago, there were 151 “first-timers” and one fewer woman, 18.6 percent, about the same as the DPRK’s Supreme People’s Assembly.

But the number of winning candidates aged 40 and younger reached 44 – three more than in 2020, although the average age of the winners was 56.7.

The ruling camp took its defeat calmly. At the time of this writing, the representatives of the Conservative parties have not claimed interference in the elections. On the contrary, Han Dong-hoon, chairman of the People Power Party Emergency Political Committee, took responsibility for the crushing defeat and resigned after serving as the de facto leader of the ruling forces for 107 days. Prime Minister Han Dok-soo and a number of high-ranking presidential administration officials also resigned. President Yoon himself promised to reflect and draw conclusions: “we will humbly accept the will of the people as expressed in the general election and do our best to renew the system of state governance and stabilize the economy and people’s lives.”

These actions, however, are less the sign of an acute domestic political crisis than a traditional element of reaction to major domestic political setbacks. However, Yoon Suk-yeol became the first president since South Korea’s democratization in 1987 to work with an opposition-controlled parliament during all five years of his presidency.

The final installment of the series will discuss what this election outcome means for the ROK’s future.

Konstantin Asmolov, Candidate of Historical Sciences, Leading research fellow at the Center for Korean Studies of the Institute of China and Modern Asia of the Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”

[1] These statistics are from KBS’s Election 2024 website