The results of the general elections held on 8 February for the lower house of the central parliament (“National Assembly”) and the assemblies of the country’s four major administrative units – Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh – have been officially announced in Pakistan.

As none of the political organisations that contested the elections won a convincing majority in the new central parliament, a ruling coalition has been formed between two parties, the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and the Pakistan People’s Party. Note that both are led by long-established family and political clans, the Sharifs and Bhutto-Zardari respectively.

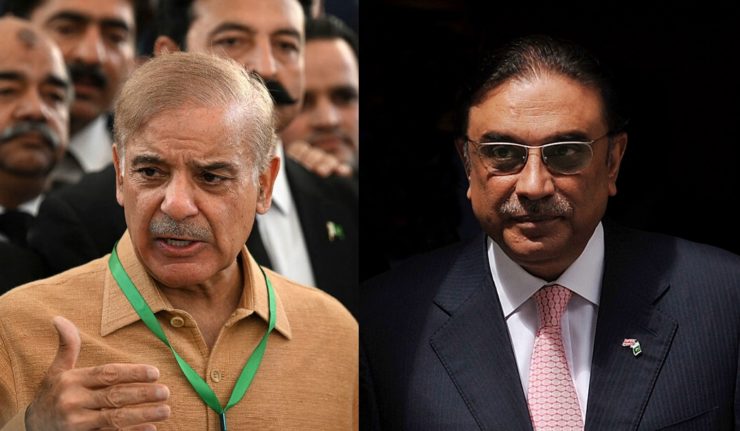

After a fierce election campaign, the two clans came to a certain (and apparently very tentative) agreement based on the division of the two main state posts, i.e. prime minister and president. Shehbaz Sharif took the first of these posts and Asif Ali Zardari the second. The PPP (Pakistan People’s Party) refused to be part of the new government, showing that the current ruling parliamentary coalition is shaky.

It should also be noted that Shehbaz’s elder brother Nawaz, the founder of the party whose name is included in the new government’s name, was considered to be the Pakistan Muslim League (N)’s candidate for prime minister until the last moment. Throughout the election campaign, Sharif himself presented his elder brother (who had already led the government three times) as the “saviour of the country”, i.e. he linked the prospect of the country’s recovery from its disastrous financial and economic situation with his assumption of the post of Prime Minister. Nevertheless, he himself returned to the post after holding it from April 2022 to September 2023.

And Sharif’s niece (Nawaz’s daughter) Maryam headed the government of Punjab, the most populous province. The main motive for appointing a member of the Sharif clan to this (also important) position was probably not so much the nepotism factor (although it was undoubtedly present), but rather the need to demonstrate the growing role of women in public life in Pakistan. In addition, Maryam Nawaz Sharif had established herself as a colourful and popular politician.

As for the election of a new president by the new parliament, Asif Ali Zardari had already served as president between 2008 and 2013. Asif Ali Zardari was already in office. It would seem that the above-mentioned bipartisan agreement would have been more to the liking of his son Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, who is now the leader of the PPP (Pakistan People’s Party). But this ambitious young (35) politician, who headed Pakistan’s foreign office during Sharif’s first term, is clearly relishing the prospect of heading a government rather than the ceremonial post of president.

In the run-up to the last general elections, the formation of a third political clan led by Imran Khan, which was rapidly gaining authority among different segments of the population, was interrupted (though perhaps only temporarily). In the summer of 2018, his party – Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) – came first in the general elections and he himself became prime minister of the coalition government. He remained in office until the spring of 2022, when he was forced to step down a year before the next general election.

The very process of Imran Khan’s early removal from power provoked a series of mass protests. Following his arrest in early May 2023 (on corruption charges), the protests turned into pogroms in a number of cities. This, in turn, gave the former prime minister’s opponents a new reason to prosecute him again and effectively bar him from contesting the upcoming elections. The PTI was also disqualified on a number of formal grounds (in particular, for failing to follow the established rules for the selection of its leaders).

Nevertheless, I.Khan, who is now serving a 14-year prison sentence, continues to lead both the PTI and the members of this party who were elected to parliament as ‘independent candidates’. It should be noted that the latter still outnumbered the elected members of the two parties of the current ruling coalition. This is in spite of all the problems that have arisen in connection with the process of counting the votes, which have led the supporters of the PTI, as well as the current leaders of this party, to claim that there has been a “massive falsification” of the results of the elections that have just taken place.

In this regard, on Sunday 10 March, large “protest marches” were held in the biggest cities of Pakistan, which again were not without “excesses”, ending with more arrests. The new government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, formed by the PTI (which won convincingly), is demanding a judicial inquiry into the counting of votes in the recent elections.

Comments by Pakistani experts on the outcomes and possible consequences of the events were cautious and sceptical. The authors of the relevant texts clearly chose (cautious) expressions, apparently guided by the principle of “do no harm”. This is understandable, since unwittingly contributing to the destabilisation of the (already complicated) domestic political situation in a country of more than 230 million people that possesses nuclear weapons is fraught with serious consequences. Not only for the country itself, but also for the surrounding region.

Meanwhile, it seems that the widespread feeling among the population that their will was manipulated in the last elections is being superimposed on, let us repeat, the difficult financial and economic situation in the country, which requires urgent action (and without regard to any sentiment). It is precisely this intention that the “new old” Prime Minister Sh. Sharif is demonstrating by promising, in particular, to “eliminate external financial dependence”. But this is for the future, of course, while in the meantime the receipt of the next tranche of $3 billion from the IMF, the terms of which are currently being negotiated, is of crucial importance.

The PPP leadership’s reopening of one of the darkest chapters in independent Pakistan’s history, the fate of first President and then Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Bilawal’s grandfather, may also prove to be a source of serious challenge to the same domestic political stability. The name of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto is associated with major changes in the country’s social structure and with attempts to establish relations with India, whose initially contentious relationship remains one of the main challenges to Pakistan’s statehood. In 1977, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was deposed in a military coup, arrested, tried and executed in 1979.

Today there are calls for a judicial inquiry into the whole of this case. Where this might lead (if such demands are met) remains unclear, given the army’s continued, shall we say, “special place” in the current Pakistani polity.

Let us reiterate the author’s position on this issue, which has nothing to do with the Pharisaic cries of “violation of the norms of democracy”. The latter are usually directed at countries ruled by “non-democrats”. Pakistan is by no means the only country where the army has to “mind its own business”. The question is how it does it, given the extreme complexity of the entire state apparatus. As for the past two years, which have seen the removal of the Khan government from power, the preparation of the next general elections and the consolidation of their results, there are probably many questions in this regard.

However, the Pakistan army leadership never tires of claiming that it has nothing to do with internal political processes.

In any case, a number of foreign statesmen sent their congratulations to Sharif on his return to the post of Prime Minister of Pakistan. Among them, the congratulations of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Sharif’s thanks to him attracted particular attention. Once again, the almost constant (with rare exceptions) state of conflict in Pakistan’s relations with India is the main foreign policy problem of the former. It is also one of the main sources of internal problems. First and foremost, these are financial and economic, as the country is literally exhausted by this confrontation.

We therefore hope that the new Pakistani government will make progress in establishing relations with its large neighbour. Mr Sharif himself has identified this as one of his top priorities.

This would appear to be essential in order to reduce tensions throughout the South Asian region.

Vladimir TEREKHOV, an expert on the problems of the Asia-Pacific region, especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”