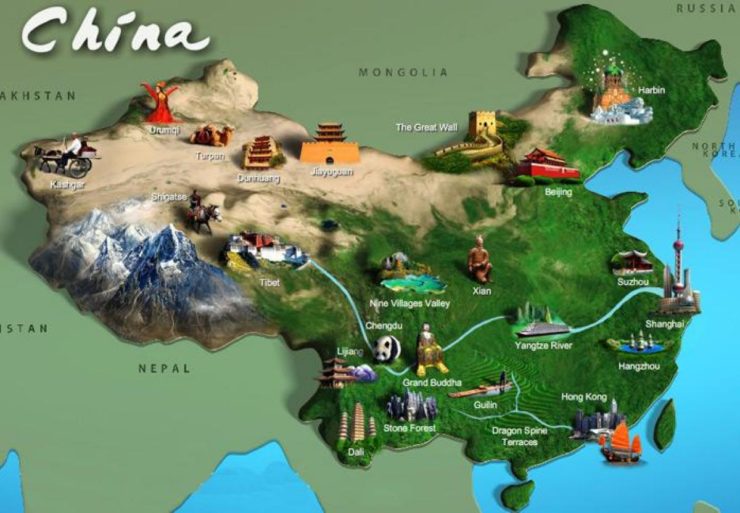

At the end of August, a seemingly trivial and commonplace incident was immediately met with suspicion by a number of countries in the Indo-Pacific region, which is literally awash with problems of all kinds. The incident in question was the publication by the PRC’s State Cartographic Service of a set of “standard maps,” which showed both its own and other countries’ borders.

It should be noted at once that these maps do not add in any way to the list of territories already claimed by the PRC, and whose possession has been the subject of disputes between Beijing and a number of neighboring states for decades. The negative response of those states was likely due to the fact that their powerful neighbor for some reason touched upon what is for them a sensitive issue in the run up to important contacts between China and those very same neighbors.

These meetings were planned in advance, and took place as part of the most recent annual summit held by the ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Since Indonesia is chairing ASEAN this year, the summits between the member states and between the Association as a bloc and a number of leading world powers were held on September 5-7 in Jakarta, the Indonesian capital.

Meanwhile, the struggle between China and the US, supported by its key allies, for influence over the countries of in Southeast Asia, a strategic sub-region of the Indo-Pacific, is intensifying. And Washington is taking advantage of the fact that most of the ASEAN member states have an interest in Washington’s involvement – and military presence – in the sub-region. These countries see such presence as a factor that helps them counter Beijing’s attempts to implement its long-standing claims to ownership of 80-90% of the fish-rich waters of the South China Sea. Including the various archipelagos located in this sea, and (according to certain estimates) vast underwater hydrocarbon deposits.

One extremely important aspect of the problem of control over the waters of the South China Sea relates to the fact that it is one of the world’s most important trade routes for a wide variety of cargoes, with goods worth several trillion dollars passing through the sea every year. For example, up to 90% of the hydrocarbon resources consumed by Japan are delivered along this route, mainly from the Persian Gulf.

That is one of the reasons why Tokyo is so eager to join its key ally in supporting the above-mentioned ASEAN countries, who have both hinted (none too subtly) and openly stated that they do not wish to be left to deal with the problem of Beijing’s territorial claims “on their own.” That explains why in the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia there have been no large-scale public protests against the regular visits of American aircraft carrier fleets to the South China Sea, or against the military exercises by the US, Japanese and Australian navies, both jointly and separately, in the region. And the governments of these countries have even fewer objections.

Given the above circumstances, it would seem that Beijing had no interest in making yet another claim for sovereignty over the waters of the South China Sea, especially since, as the NEO has already reported, these claims were rejected in summer 2016 by a decision of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague. But the PRC did not participate in those arbitration proceedings, which were initiated at the request of the Philippines, and, naturally, it does not recognize their outcome, the question of the origin and validity of China’s so-called “nine-dash line,” which defines the scope of its claims in the region, remains unclear.

When the Communist leadership came to power in China in 1949, it inherited that line from the its predecessor, Chiang-kai-shek’s Kuomintang government. But when China published its new map of the country on August 28 this year, the line became a “ten-dash line,” with an additional dash east of Taiwan. China was thus asserting its claim to that island.

To the present author it is unclear why China should publish a new version of this line immediately before extremely important (and, as already stated, prearranged) contacts between the Chinese Prime Minister Li Qiang, who represented China in Jakarta, and his ASEAN colleagues. After all, this revision of the line is in direct opposition to the course adopted by Beijing in recent years, which has been aimed at easing tensions with its southern neighbors. A course that Li Qiang continued to uphold in the Jakarta summit. Meanwhile, Manila, Hanoi, and Jakarta, either indirectly or directly, reacted negatively to Beijing’s redefinition of its old territorial claims in the South China Sea.

During an “informal” trilateral meeting between the Japanese Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, the US Vice President Kamala Harris and the Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., held on September 6 in Jakarta on the sidelines of the above-mentioned ASEAN summit, the three countries declared their intention to jointly combat “unilateral attempts to change the status quo” in the South China Sea, and to “strengthen coordination” of their efforts. In general, this is a well-established formula of American diplomacy, which has frequently been adopted in recent years in relation to the situation in the South China Sea, in relation to Taiwan and in the East China Sea. In the present case the use of this formula was clearly a response to the publication, one week before, of China’s new maps.

Just two days after their publication, Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs challenged China’s claim, stating that “Vietnam has sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly archipelagos.” It should be noted that the country in possession of both of these archipelagos (which are known by other names in China, and which are located respectively in the north and center of the South China Sea) in effect controls the entire South China Sea. Significantly, both Vietnam and the Philippines also have their own names for these island groups.

It should be noted, by the way, that the territorial dispute between the PRC and Vietnam is one of the main reasons behind one of the most surprising metamorphoses in the global political process over the last two decades. It relates to the gradual rapprochement of Hanoi and Washington, which were, until relatively recently, deadly enemies. The visit to Vietnam by US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin two years ago was a vivid illustration of the change in relations between the two countries. And it is clear that when Joe Biden visits the country on September 10 he will be received warmly.

He will travel to Vietnam from India, where he will take part in the 2023 G20 summit from 8-9 September. One can predict with no less confidence that his reception in New Delhi will be equally enthusiastic, and his face-to face meeting with the Indian prime Minister Narendra Modi will be their third in less than a year and a half.

And just as in the case of Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia, India’s rapprochement with the US, China’s main geopolitical opponent, is largely a response to New Delhi’s territorial dispute with Beijing. China’s new “standard maps” also touch on that dispute – they depict the entire Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh as Chinese territory.

The present author by no means considers this claim by Beijing to be completely unfounded. After all, it is impossible to ignore the fact that, taking advantage of the chaos afflicting the Chinese state at the beginning of the 20th Century, culminating in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, a certain official in the British Raj administration drew the so-called “McMahon Line” on the map, thus separating from Chinese Tibet the territory that would become the state of Arunachal Pradesh.

As already noted, the issue is simply how and when China has chosen to asset its claims. And it happened on the eve of the two important international events referred to above, in both of which the Chinese leader Xi Jinping could easily have been a participant. As it was, he did not attend both events. His absence from the G20 summit in New Delhi has been attributed by many to the lack of real progress in relations between the two leading global powers, despite their recent ministerial-level contacts to “test the water.” Given that lack of progress, the inevitable meeting between the US and Chinese leaders would not have borne any fruit.

In view of the present author’s opinion, a far more significant factor was the Chinese leader’s unwillingness to hear from his Indian counterpart any further remarks similar to the proposal made on the sidelines of the last BRICS summit. That proposal was that any future improvement of relations between China and India be linked to the stability of the situation in the area of the de-facto border between the two countries (the so-called Line of Actual Control, or LAC). Not so log ago an unpleasant incident occurred at a site along the LAC. Had he attended the G20 summit, Narendra Modi would have spoken to him on the sidelines of the meeting and asked him an inconvenient question, something like, “In view of our last conversation at the BRICS summit, how should we understand the recently-published maps of China?” India’s Foreign Ministry has officially objected depiction of Arunachal Pradesh as Chinese territory in the maps.

To conclude, let us briefly touch upon the wider issue of the influence of certain global powers on the development of the situation in the Indo-Pacific region, which is, increasingly, the main focal point of the current stage of the Great Game of global politics. In the present author’s opinion, there is no need to multiply entities and speculate about the involvement of extra-regional factors in order to explain the main cause of the problems in the Indo-Pacific region. The United States is often presented as the “source of the world’s ills” and accused of treating its allies as vassal states. This cartoonish propaganda image is just a mirror image of the kind of naive rhetoric that Washington uses to tar its opponents.

In fact, as China’s new “standard maps” clearly demonstrate, almost all the significant problems in the Indo-Pacific region are actually “local” in nature.

Vladimir Terekhov, expert on the issues of the Asia-Pacific region, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.