Yoshimasa Hayashi, the foreign minister of Japan, paid a visit to China on April 1-2 of this year, and everything that went along with it ended up being rather indicative of the complex and contentious processes going on throughout the Indo-Pacific area as a whole, since during this visit, the complicated relationship between two of the many important participants in these processes was discussed.

We should note at once that the talks in Beijing ended without any noticeable positive results, and the state of bilateral relations can continue to be described by the same (politically correct) term “complicated”. Proof of this is the rarity of the very acts of the negotiation process which if they have happened recently at all, then on the occasion and in the margin of various international platforms. When, as they say, “parting in the corridor without noticing each other” would have looked quite unseemly. By the way, the discussed visit of Yoshimasa Hayashi was postponed several times.

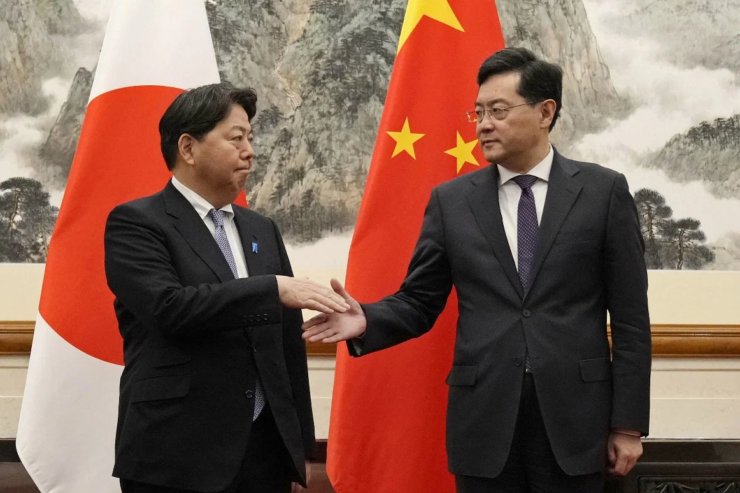

When it finally took place, then over the course of one day (April 2) the PRC’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang, the newly appointed Premier Li Qiang, and the current second in command of Chinese foreign policy (after President Xi Jinping) Wang Yi held consecutive talks with the guest.

As far as we can understand, the substance of the entire negotiation process was the subject of the first meeting, which was also the longest. The third stage, apparently, was a kind of “final review” of what had been discussed during that first meeting. The second stage (which lasted 40 minutes) was designated on the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s website as a “courtesy visit” to an important new person in the PRC leadership hierarchy.

Let us point once again to the main component of the mentioned contradictory nature of Japan-China relations, which is quite typical for many paired configurations comprised of other Indo-Pacific countries. Which, we note, include the United States, i.e. simultaneously the main ally of Japan and the principal geopolitical opponent of the People’s Republic of China. Washington itself has been constantly insisting in recent years that the United States belongs to this region.

As for the inconsistency in the overall picture of relations between China and Japan, until recently one could speak of a more or less prosperous state of economic relations, which was contrasted to varying degrees by a steady process of degradation in the political sphere. In general, the same picture was observed in the system of relations between China and the United States.

But in the past few years, Washington has turned entire sectors of the economy into a field of struggle with its main geopolitical opponent. First of all, those that operate with the so-called “high technology”. At the same time, persistent attempts are being made to draw the closest allies, primarily Japan, into the new field of struggle with Beijing.

Recall about the recent institutional and legislative measures taken by Washington to block China’s access to the world system of development, production and marketing of advanced microelectronic semi-finished products (chips). The latter are now increasingly becoming a critical element of the final products (including military) of the above mentioned “high technology”.

Japan now joins the US (and the Netherlands with its critically important ASML) in restricting China’s access to interstate “supply chains” for chips. At the end of March, that is, on the eve of Yoshimasa Hayashi visit to Beijing, strengthening of export control was announced over a number of “instruments” manufactured in Japan, which are used in the above-mentioned production and logistics “chain”.

Apparently, the issue of Japan’s involvement in the US anti-Chinese chip making measures was among several major issues that were raised before the Japanese guest by the hosts of the meetings held in Beijing. It is noteworthy, however, that the topic was not mentioned at all in the reports issued by the Japanese Foreign Ministry.

Meanwhile, reports on a number of countermeasures planned in China, which came immediately after the meetings, show that little headway had been made in preventing a “high-tech war” during the talks. First, it is reported that an appeal to the World Trade Organization (WTO) is being prepared with a request to review the aforementioned Japanese export restrictions for their compliance with the statutory provisions of this organization.

Secondly, there are plans to introduce controls on exports from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) of rare-earth magnets. These latter are also extremely important, especially in the manufacturing of modern electrical products and, above all, in the advanced automotive industry. And since China is almost a monopolist both in REM mining and production of electromagnetic semi-finished products based on them, the most important industries mainly of the US and Western Europe may be under threat.

Japan, on the other hand, has some opportunity to avoid such a prospect, since it maintains some ties with Chinese manufacturers of these products. It has even been claimed that the technological know-how of Japanese companies was used in the organization of their production ten years ago in China.

But overall, it seems that Washington (and Tokyo in its wake) had hardly calculated, at least their first subsequent moves in the dangerous game that began with attempts to isolate from modern technology a country of such importance in the world economy as China already is.

Yet the main contribution to the thickening shadow over Japan-China relations as a whole is, we repeat, their political component. The adoption of Japan’s new National Security Strategy with its clearly defined anti-Chinese orientation was another very significant act in this sphere.

Moreover, that document already serves as the basis for launching a fundamentally new phase of the country’s military development, during which the Japan Self-Defense Forces (one of the most powerful armed forces in the world operating under this euphemistic name) will take on a completely “traditional” appearance. In other words, the JSDF will have the ability to conduct preemptive offensive operations in order to “prevent the expected strikes by a potential enemy.” The role of the latter continues to be faithfully performed by North Korea. In fact, however, we have long been talking about a much more important contender for this role.

China is also wary of the impending publication of a foreign policy white paper that Japan is preparing. Leaks in the media space about some of its main provisions, among which the thesis on the “greatest strategic threat” from China may be the most important, provoke understandable comments from Beijing.

The generalized message of the hosts of the Beijing meetings, which was addressed to the (rare, I repeat) guest, was to advise him not to involve Japan in the “US efforts to encircle China.” In turn, the countermove was the guest’s statement of his country’s interest in “maintaining peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait,” as well as “concern” over the situations in Hong Kong and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

There was also an exchange of views on the topic of the upcoming dumping into the ocean of a million tons of “decontaminated” water from the cooling system of the damaged Fukushima nuclear power plant reactors. The Chinese side expressed concern over this issue, while the guest said there was nothing wrong with the level of purification.

Finally, we note that after the completion of the discussed visit to China by Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi, no noticeable positive shifts in relations between the two leading regional powers have occurred. That is evidenced by the lack of clarity regarding at least continued contacts between the foreign ministers of the two countries.

For China, however, more serious evidence of this was the fact that on April 3 (i.e., the day after the visit to Beijing ended) the same Hayashi visited Belgium and had a meeting with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. The reaction in China to the publicly announced outcome of their talks was quite predictable.

The news of the completion of the Hotline between the defense ministries of the two countries is a rare positive act (more of symbolic significance, though) in Japan-China relations lately. This was done in order to prevent “unwanted incidents” that may arise while the sides’ coast guard ships are in the disputed areas of the East China Sea.

And this has been happening with increasing frequency in recent years.

Vladimir Terekhov, expert on issues of the Asia-Pacific region, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.”