On July 1, the PRC celebrated the very remarkable event that occurred exactly 25 years earlier with the return of Hong Kong to the country. It was not only extremely important for China itself, but also had a significant foreign policy component. And the importance of foreign politics only increases with time.

This was borne out by the varied attention paid by the United Kingdom, which held the territory of Hong Kong for a century and a half, the US and some other Western countries during the PRC commemoration of the event. As fears grow in Washington and London (regardless of whether justified or not) over the process of China’s transformation into a new global power, the situation in Hong Kong is now as high on the list of reasons for propaganda attacks against it as everything that is happening in the country’s “domestic” Autonomous regions (Tibet, Xinjiang Uyghur) and around the Taiwan issue.

As for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the main pretext for such attacks is Beijing’s alleged violation of the Chinese-British “Declaration” signed in 1984 by the leaders of both countries at the time, Deng Xiaoping and Margaret Thatcher. According to this document, Hong Kong was to be in a “50-year transition state” from the date of hand over to the PRC, which, however, was not spelt out in detail.

However, there is no doubt that the prolonged “freezing” (which was, however, rather the default plan) of Hong Kong’s political and legal status, which had been created by July 1, 1997, was unacceptable to Beijing. Having been influenced by a culture foreign to China for 150 years, Hong Kong has re-emerged as a foreign body, which may well have become a source of “political contamination” for China’s entire social body.

It is possible, incidentally, that Thatcher’s government viewed the process of placing Hong Kong under Beijing as a time bomb, which would have, sooner or later, undermined the current Chinese political order from within. To do this, of course, for a long time the latter’s leadership should not have had any effective instrument to influence the situation inside Hong Kong itself. Hence Thatcher’s demand for a “50-year transition period” as a precondition for handing over Hong Kong to China. Although formally, 1997 was simply the end of a 99-year “lease,” under which London owned Hong Kong throughout the 20th century.

To a certain extent, Deng Xiaoping’s “One country, two systems” concept was a response to this demand. Since the very category of “system” as applied to state structure is rather rubber-stamped, this formula of the then Chinese leader encapsulated the possibility of adjusting Hong Kong’s political “structure.”

Meanwhile, the need for it gradually came to the fore as the comprehensive US-China competition in the international arena intensified, with Hong Kong coming to be seen by Washington and London as a field and an instrument to fight against the new geopolitical rival.

Since returning to China, the situation in Hong Kong, which has always been in a state of varying degrees of turbulence, has undergone several periods of fairly serious aggravation. In order to finally bring the political processes in the critically important Special Region under control, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress adopted the Hong Kong National Security Law on June 30, 2020. During the process of Hong Kong’s gradual incorporation into the PRC state-legal framework, this act was an important milestone. It also served as another excuse to intensify anti-Chinese propaganda attacks by Washington and London.

For Beijing, it has, among other things, allowed to solve the crucial problem of ensuring control over the process of the next re-election in Hong Kong of a new local Legislative Council (a kind of unicameral parliament). The former deputies were what they call “particularly rowdy” and caused a lot of trouble for both the Central Government and the local Administration, led by Carrie Lam, until recently Chief Executive and quite loyal to Beijing.

It seems that Hong Kong’s parliament, which was formed as a result of the December 2021 elections, will now be “quiet and calm.” It should be noted, by the way, that this electoral process, which was supposed to take place in autumn 2020, was postponed for a year under the pretext of all sorts of threats from the COVID-19 epidemic.

The procedure for handing over the post of head of the local Administration (after Lam’s term of office had expired) was just as smooth and trouble-free this year. On the June 1 holiday, it was taken over (confirmed by the results of the previous month’s election) by John Lee, formerly in charge of security and of suppressing the repeated “protests” (on various occasions), among other things. The Global Times had a good reason to call the new head of the Hong Kong Administration a hardliner. Parting with the past in the structures it previously controlled also extends to relative trivialities. In the police, for example, the answer “Yes, Sir” to an order from a superior, is now revoked.

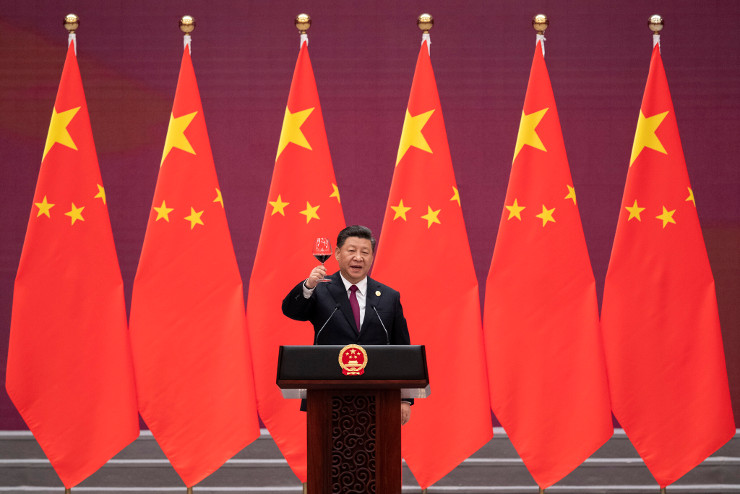

Nevertheless, it should be noted that in the process of “tightening the screws” in Hong Kong, the central government is nevertheless trying to stick to some measure, guided by two main considerations. First, within the framework of the “One country, two systems” concept to which Chinese leader Xi Jinping reaffirmed his commitment during a visit to Hong Kong, the residents of this Special Region need to feel that they retain a certain “specialness” as part of the (not least and still) new country. Some form of reprisals (moderate in the author’s view) are taken against the most “hardened” public activists, not only the street ones who engage in all sorts of outrages during demonstrations waving British flags, but also the owners of certain publications that publish texts that are blatantly defiant of the Central Government and the local Administration.

Second, the equally complex and crucial issue of Taiwan’s return to PRC jurisdiction is not overlooked. From the former, everything that happens in Hong Kong, as well as in TAR and XUAR, is watched very closely. Taiwanese should not have a negative impression of the Central Government’s policies in the “peripheral-national” administrative areas of the PRC. Should any serious fears arise among Taiwanese regarding the consequences of (potential) incorporation into China, Beijing will have to abandon its plans to resolve the Taiwan problem peacefully. It should be added that this would be entirely preferable to China’s leadership.

Finally, it should be noted that the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s reincorporation into China was the occasion for yet another bitter retort to Beijing by its “best friends” represented by Western statesmen such as Anthony Blinken, Liz Truss, senior EU officials and politicians from individual European countries. Earlier occasions have included measures to neutralize the “protesters” rampaging through the streets of Hong Kong, the adoption of the aforementioned “Security Law,” the formats for elections to the local parliament and a new head of the Administration. The content of the claim is still the same: “China’s violation of the terms of Hong Kong’s return.”

The Chinese Foreign Ministry is of course reacting to this grumbling, which however has no effect on the process of Hong Kong’s gradual incorporation into the country.

Vladimir Terekhov, expert on the issues of the Asia-Pacific region, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.