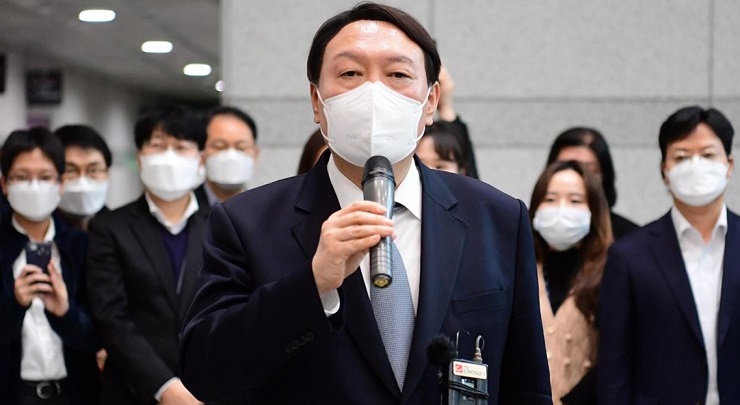

After describing the Conservatives’ internal party problems, it is time to talk about the scandals accompanying Yoon, because as the election nears, the author gets the impression that the 2022 election is unprecedented in terms of mudslinging by the candidates on each other.

On the one hand, Yoon and his family have been spared a number of unpleasant criminal cases and now, for example, his convicted relatives cannot be spoken of. On December 3, the Seoul Central District Court rejected for the second time an arrest warrant for prosecutor Son Jun-sung, through whom Yoon allegedly tried to file criminal complaints against influential Democratic Party members by initiating parliamentary enquiries from Conservatives, backed by incriminating evidence. The court ruled that the Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials (CIO) had not provided sufficient grounds for the arrest. Son’s arrest had been considered a key bellwether of whether the CIO would be able to charge Yoon, who was Son’s direct superior at the time.

On January 25, the appeals court acquitted Yoon Suk-yeol’s mother-in-law, striking down a prison term handed by a lower court on charges of taking state health insurance benefits after illegally opening a care hospital for the elderly in February 2013 without a medical license. She was also cleared of charges that she had illegally accepted 2.29 billion won (US$2.02 million) in state benefits from the National Health Insurance Service until 2015 to run the hospital.

On the other hand, the repulsed attacks were replaced by new ones. Yoon Suk-yeol’s wife, Kim Keon-hee, has once again found herself at the center of a scandal. According to news reports, between July and December 2021, Kim had numerous phone conversations with a man who works for the liberal YouTube channel “Voice of Seoul” (52 conversations for a total duration of seven hours) and revealed a lot of things. The journalist then declared his intention to make the contents of their talks public and handed over the tape to the MBC, one of the most influential TV channels in the Republic of Korea.

On January 13, the opposition and Kim Keon-hee tried to prevent this by filing a court request not to publish the contents of the talks, pointing to the recordings being obtained illegally. On January 14, however, the court ruled to allow the recordings to be published on the grounds that the people have a right to know the real views of the entourage of a man running for president; since “Kim is considered a public figure, the broadcast of parts of the recording falls in line with the common good.” The only parts of the conversations that were banned from public disclosure were those involving only Kim Keon-hee’s personal life and facts relating to cases under investigation.

So, what’s the deal with Kim Keon-hee’s remarks? The most controversial were her words on the hot topic of MeToo. Kim accused Moon Jae-in’s administration of needlessly inflating the problem and trying to find sexual aggressors who “make people’s lives so dry.” Speaking about the scandal involving former South Chungcheong provincial governor Ahn Hee-jung (MeToo’s first victim, jailed on the second attempt for raping his secretary), Kim said she felt sorry for him, adding “my husband and I are very much on Ahn Hee-jung’s side.”

From the author’s point of view, this is a really unpleasant remark, especially in the context that when the Ahn Hee-jung scandals came to light, Conservatives were actively engaged in moralizing. And now it turns out that the candidate’s wife herself says that raping secretaries is the norm, as long as they get paid to keep quiet. Sure, there are other ways to interpret these phrases (e.g. that those who don’t get paid are using the MeToo topic in retaliation), but let’s not engage in sophistry.

Then, Kim asked the journalist to help Yoon’s election camp and promised to pay him 100 million won (US$83,000) if Yoon won the election. The journalist was called to give a lecture to Yoon’s headquarters and was promised a fee.

In the same context, she asked her interlocutor to drown Hong Joon-pyo (Yoon’s main rival within the party) by posing to him “some tough questions” at a forum at Seoul National University, where Hong was to attend as a keynote speaker.

The mocking remarks about Conservative politicians went on and on. According to Kim Keon-hee, Yoon became influential because of the Moon administration, not the Conservatives. In fact, “some idiots” believe that the impeachment of former president Park Geun-hye in 2017 was caused by liberals, when in fact it was “executed internally within the conservative party.”

Finally, Kim denied the rumor that she was a beauty salon owner named Julie and sometimes provided escort services, which is illegal in Korea.

Oddly enough, Yoon’s wife’s revelations did not cause his ratings to plummet. Perhaps the public has had enough of scandals, perhaps it is the fact that at the same time there was a scandal with the book “Goodbye, Lee Jae-myung” mentioned in earlier articles, or perhaps attempts to defame Yoon through his wife, spitting on privacy, have indicated that the Democrats have no other arguments against him.

There has, however, been quite some noise. Kwon Young-se, head of the Yoon’s election committee, said MBC and the YouTube journalist had committed “political sabotage” and demanded that the broadcaster rectify the situation by “equally airing segments about the familial feuds involving Lee Jae-myung.”

DPK spokesperson Kim Woo-young responded that Kim’s efforts to buy support for Yoon’s camp were an infringement of election laws, which state candidates and their wives cannot give money to outsiders. Regarding remarks on #MeToo, “if a presidential candidate and his wife share anti-social views that run counter to human rights, then it is a serious problem,” and generally, “how can a party that can’t even rationally evaluate a potential first lady govern the citizens and the country’s state affairs?”

Kim Ji-eun, who worked as a secretary for An Hee-jung, also demanded an apology through the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center. Yoon Suk-yeol apologized on behalf of his wife.

But much more eye-catching was Kim Keon-hee’s remark about her contacts with spiritual guides. The fact is that Moon Jae-in’s core electorate and part of the fake news public continue to believe that Park Geun-hye was a puppet in the hands of a shaman and all wrong decisions were dictated to her. And because the candle revolution was perceived as a victory for Moon over such practices, the Democrats are trying to portray Moon not as an honest prosecutor, but as a puppet of scary shamans. On February 14, the Segye Ilbo newspaper reported that a shaman introduced by Kim to her husband had unduly influenced Yoon’s campaign by working as an adviser for a subunit called “Network Headquarters”.

On January 19, prosecutors launched an investigation into Yoon Suk-yeol for violating the country’s electoral laws, leaking confidential government information and abusing his power to undermine law enforcement agencies. The allegations made by the Democratic Party refer to the fact that in February 2020 Yoon, then attorney general, ordered the police not to search the headquarters of Shincheonji Church, accused of a major cluster infection that resulted in more than 5,200 cases of COVID-19 in Daegu earlier this year. The source of the accusation comes from the same Segye Ilbo, according to which Yoon did not carry out the order because a certain fortune-teller named Geonjin advised him not to dirty his hands with unnecessary blood. If the newspaper is to be believed, “mounting reports suggested that Geonjin’s relationship with Yoon and his wife Kim Kun-hee went deeper than the couple reluctantly admitted.”

But can this newspaper be trusted? The author well remembers Segye Ilbo’s editor-in-chief saying five years ago that he had in his possession eight secret files, the full publication of which would blow up society because they contained shocking evidence that Park Geun-hye had rigged elections and planned political assassinations. People were outraged, oil was poured on the flames, but the files were never published. And now the evidence that Yoon is under the influence of shamans is very reminiscent of the story of the (miraculously found, then removed from the evidence list as fake) tablet of Choi Soon-sil.

The opposition has denied the accusation.

The shamanism scandal, however, also affected Lee Jae-myung’s election camp, when the conservative Chosun Ilbo newspaper reported that a committee of 17 religious leaders had been set up there on January 4, one of whom was a well-known prophet who heads the country’s official prophet association and had correctly predicted all Korean presidents from Roh Tae-woo to Park Geun-hye.

Lee’s election committee admitted to inviting the leader to the camp, but said it was one thing to have a prophet widely known in political circles and another to have secret advisers out of nowhere.

Here are some conclusions. While there are potentially real criminal cases against Lee Jae-myung, like Seongnam Gate for example, there are no accusations of such weight against Yoon, which prompts his detractors to try and either get him through his wife or promote the “shamanistic angle” by playing on fears from five years ago. But the sheer amount of mudslinging and dirty laundry alone can lead to a certain oversaturation, where every new revelation will no longer have any effect and will elicit a reaction along the lines of either “we’ll choose the lesser evil” or “enough with fake news already, nobody believes you anymore.”

In such a situation, the protest vote factor may play in Yoon’s favor, although this author has written about Yoon’s problems in the event of a presidency, and these do not seem to be going anywhere. Yoon promised that if he came to power, Kim Keon-hee would not influence politics as the first lady and even promised to disband a number of relevant structures of the Blue House, but what will come of this will be assessed after March 9.

Konstantin Asmolov, PhD in History, leading research fellow at the Center for Korean Studies of the Institute of the Far East at the Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.