At the end of April 2021, the US administration finally unleashed the new concept of policy toward North Korea that the expert community had long awaited. The waiting period was, of course, accompanied by occasional statements by press secretary Jen Psaki that the process was underway, as well as analytical reports and statements by experts who wanted to steer Washington’s thinking in the right direction. For example, while Yang Mu-jin, a professor at the University of North Korean Studies, advocated confidence-building, former foreign minister Yun Byung-se compared all previous attempts to negotiate with the DPRK to the “Munich collusion” and even the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which led to the collapse of South Vietnam two years later.

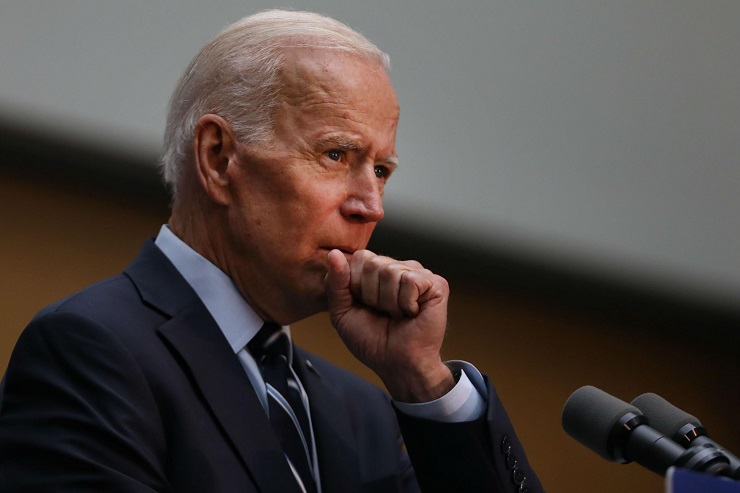

All of these statements were actively relayed by the conservative media in the ROK, pointing to the contrast between the course of Biden and that of Moon Jae-in, who continued to emphasize the DPRK’s desire for denuclearization and sought to achieve results here before his resignation. It was emphasized that, unlike Trump and Moon, who took a top-down approach, where first the top officials agreed on something and then those agreements were worked out, Biden would consult more with allies and trust experts, relying on their analyses rather than spontaneous voluntaristic decisions.

On February 12, State Department spokesman Ned Price said that the North Korean nuclear issue remains a top priority for the US government, despite the lack of direct engagement with the DPRK.

On February 22, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stressed that Washington will continue to strive to denuclearize North Korea and work closely with allies and partners to combat North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programs and ballistic missiles.

On February 24, US Senator Thomas Suozzi noted that the US is unlikely to ease or lift sanctions unless Pyongyang shows its good will, even if in general North Korea cannot be trusted. Suozzi noted that the North Korean people are not suffering because of the sanctions, but because of the North Korean leadership, and therefore, compared to the Obama administration, Biden’s policy should be “more strategic and less patient”.

On March 2, former national security adviser McMaster noted that the US and its allies must maintain maximum pressure on the DPRK to make Pyongyang realize that it is safer without nuclear weapons than with them. He believes that previous denuclearization efforts were based on two erroneous assumptions: first, the hope that North Korea’s openness would change the nature of the regime, and second, the notion that the Kim regime was unstable and would collapse before it could develop nuclear weapons. At the same time, McMaster remarked that the US should make it clear to Kim Jong-un that their goal is not regime change.

On March 3, 2021, in his first major address as secretary of state, Blinken outlined eight priorities for American diplomacy. Even though North Korea was only briefly mentioned as one of the countries that pose a serious challenge to the US (along with Russia and Iran), it does not compare to “the greatest geopolitical challenge of the 21st century, which is the US-Chinese relationship”. On the same day, Undersecretary of State Wendy Sherman noted that the United States should use all means to prevent the North from developing its nuclear capabilities, stressing the importance of partnerships, including with China.

Shortly after Blinken’s statement, Joe Biden noted that the US administration would give its diplomats greater authority to limit the threats posed by the DPRK. It is not yet clear what was meant by that.

In March 2021, during his first White House press conference, Biden said that North Korean missile launches violated UN Security Council Resolution 1718. “We are consulting with our allies and partners, and there will be a response if they decide to escalate. We will respond accordingly.” When asked whether he agrees that North Korea is a major foreign policy issue, Biden also replied in the affirmative.

For the author, this was a crucial point, since the launch of short-range missiles was equated with the launch of more serious missiles, and, according to some reports, was the reason for probing within UN structures in order to increase sanctions pressure under this pretext. However, Russia and China fiercely opposed it, and the case did not move beyond preliminary consultations.

On March 26, Jen Psaki said that a new policy approach toward the DPRK was in the final stages, and added on March 29 that Joe Biden had no intention of meeting with the North Korean leader because his North Korean policy would be “completely different.”

On April 7, Jen Psaki said the US was willing to consider diplomatic contacts with the DPRK if they led to denuclearization, but on April 9 she actually reiterated McMaster’s thesis that sanctions were not aimed at the North Korean people. Psaki also said that the US side is mulling options for humanitarian aid to the North, despite the stalemate in negotiations.

On April 28, in his first address to the nation, Biden called Pyongyang and Tehran’s nuclear programs a serious security threat to the United States and the world, which America will confront through diplomacy, firm deterrence and working with allies. The head of the White House noted that “no one nation can handle all the crises of our time alone, from terrorism to nuclear proliferation, mass migration, cyber threats, climate change, and pandemics”. Joe Biden said that the US would maintain a military presence in the Indo-Pacific region as strong as in Europe, “not to start a conflict, but to prevent one”.

On April 30, Jen Psaki finally announced that the US had “completed a thorough, rigorous, and comprehensive review of DPRK policy. Our goal remains the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” The presidential spokeswoman noted that the Biden administration does not plan to pursue the same policy system toward Pyongyang that teams of past US leaders have used, because their actions have not yielded any actual results in denuclearization. Psaki added that the new United States policy “requires a measured, practical approach that is open to and will explore diplomacy with the DPRK”. Close cooperation with South Korea, Japan, other allies and partners, as well as outside experts and representatives of previous US administrations was noted.

On May 2, North Korea responded with a statement from Kwon Jong-geun, head of the DPRK Foreign Ministry’s Department on US Affairs. Kwon released a press statement criticizing the performance of the unnamed “ruler of the United States”. “Our self-defense deterrent force is being passed off as a threat,” the ROK and US military exercises truly show who threatens whom, and “the US ruler has made a very big mistake”. “That’s the kind of thing we always hear from Americans, and it’s already been speculated”: Washington “will continue, as before, the hostile policy against the DPRK that the United States has pursued for more than half a century”. If the US continues with its Cold War approach, there will be a crisis between the two countries. “Now that the basic idea of the new US North Korean policy has become clear, we will be forced to take appropriate measures, which will put the US in a very difficult situation over time.”

Almost immediately thereafter, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan noted that American policy toward the North is not about hostility, but about finding solutions. Sullivan said America is looking for practical ways to move the denuclearization process forward, and it will be a more calibrated, measured and practical process.

US and ROK experts immediately tried to speculate what the North would do in response to Biden’s actions, mainly guided by Kim Yo-jeong’s previous statement, where she promised to abolish a number of structures related to inter-Korean relations. In addition, there are new launches of short-range missiles expected. However, at the time the author writes this text, there were no new launches yet.

To summarize: if we put aside the fancy language, the author identifies the following points, to which he draws attention.

First, full denuclearization is still the stated goal of the policy, without specifying whether this means only nuclear disarmament of the DPRK or, as suggested by vocal voices like Bolton, depriving the DPRK of all weapons of mass destruction and the missile program as well.

Second, the rejection of the “big deal” concept has been declared, which indicates two things. For one thing, Washington is not going to make any obvious concessions, especially in the form of lifting or easing sanctions; there is also a clear hint of the corresponding rhetoric of Donald Trump, whose policies Biden has actively criticized and, judging by this declaration, does not intend to repeat.

Third, a new policy is declared, which will not be a copy of “strategic patience,” the essence of which was de facto reduced to waiting for the collapse of North Korea for domestic political reasons. After all, it was assumed that without force majeure Pyongyang would not give up its nuclear program anyway. Technically it gives a different framework and provides a corridor between the policies of notional Trump and notional Obama, actually declaring that something new is being invented.

Fourth, the influence of diplomacy is emphasized, but not so much in resolving conflicts by political-diplomatic means as in “forming an international community” that will conduct this policy cumulatively; primarily, the interaction with Japan and the ROK as major regional allies.

In the author’s opinion, several factors influenced this choice.

First, the United States categorically opposes the collapse of the nonproliferation regime because it undermines the hegemony of the Big Five. Although, if the NSNW regime collapses, potential nuclear powers could include US allies, a nuclear-armed Taiwan could be a very unpleasant thorn in China’s side. America will have to deal with matters such as a nuclear Iran, and besides, it is not clear how obedient the traditional allies will remain by getting their nuclear umbrella instead of the American one.

Second, the logic of factional infighting and US public opinion also prevents American politics from moving beyond certain limits. Anything that might look like a unilateral concession to a tyrannical regime is inexcusable and unacceptable.

Third, there is a sense that, although North Korea cannot be dismissed as a routine “threat to peace,” the new US administration actually has more serious adversaries that will require priority efforts to deal with. In foreign policy, it is China; in domestic policy, it is the notorious “white supremacism”.

This is why the new US policy has elicited different assessments. Some have dubbed it “the policy of sitting on the chair, menacingly,” since there is no way to stop the North with acceptable methods, but it cannot be acknowledged. Others, on the contrary, believe that the United States has given itself maximum leeway and will actively act according to the situation, using an arsenal of different methods: continuing to work with allies to pressure China, including on the North Korean issue, increasing pressure through the human rights agenda, and perhaps veiled support for anti-North Korean provocations so that an angry North would step over the “red line”.

In this context, the author draws attention with dismay to the actions of the “Free North Korea Fighters,” who have carried out another launch of leaflets across the border, despite the law that expressly forbids it. Nevertheless, at the time of writing, the initiators of this action have not yet been arrested. In the meantime, we will wait for the new administration to take tangible steps, as there is always some difference between a declared policy and its implementation.

Konstantin Asmolov, PhD in History, leading research fellow at the Center for Korean Studies of the Institute of the Far East at the Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook“.