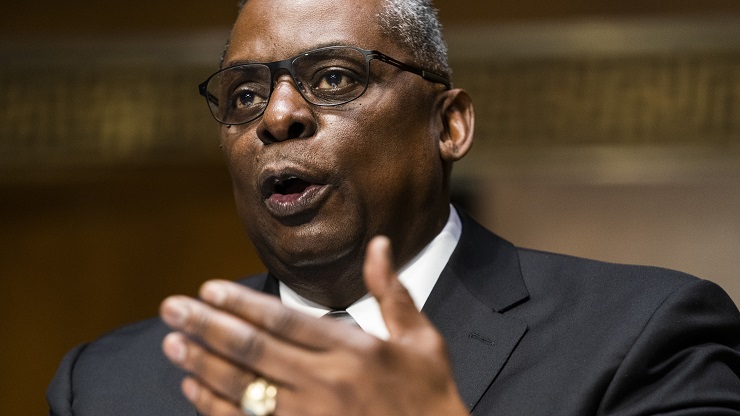

Beginning on March 19 of this year, the three-day visit to India by US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin was the final act of his first foreign tour after being appointed to this post in the administration of President Biden.

Previously, along with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, he visited Japan and the Republic of Korea, that is, two countries that are allies with the United States, but far from it with regards to one another. By appearances, no progress has yet been made in resolving the long-standing issue associated with these circumstances. It is unlikely that the Koreans will change (at least in the near future) into some kind of anti-Chinese coalition (especially with the participation of Japan), the task of forming which is becoming increasingly important for Washington.

After visiting Seoul, the future paths of the two high-ranking American government officials parted ways. Blinken went to the capital of Alaska, Anchorage, to sort out relations with no less high representatives of his main geopolitical opponent. Meanwhile, Austin flew to Delhi in order to continue the attempts of drawing India into the orbit of American politics, which, with some success, was undertaken by previous US administrations.

The growing importance of India in Washington’s plans to form a regional anti-Chinese coalition explains the unprecedented number of people of Indians origin in the new American administration. An undoubtedly significant character was attached to the choice of the half-Indian Kamala Harris to the post of US vice-president.

Lloyd Austin’s arrival fell on another period of exacerbation of the internal situation, which in such a gigantic and extremely complicated country like India cannot but be multifactorial. The increasing intensity of inter-party struggle (in particular, over the upcoming elections to local parliaments of a number of difficult states) is imposed on the actualization of social and inter-religious factors.

Of these, the first is associated with incessant protests from farmers against the government’s strategy for reforming the country’s agriculture. The second is due to the continued complexity of the situation in the state of Jammu and Kashmir after the well-known measures taken in 2019 in the areas of both the administrative reform of this state and the acquisition of Indian citizenship by refugees. Both provoked serious Muslim protests.

In turn, the clashes between farmers and Muslims with the forces of law and order gave rise to interference in Indian internal affairs by various branches of the international “human rights” movement, which (along with the “ecologists”) prey on the real problems of mankind.

However, given India’s current de facto international status, “human rights” card cannot be played against it. The UN Human Rights Committee, if it were to attempt such games, would quickly receive a cold shoulder. Even the seemingly invulnerable symbol of the most advanced social movements like Greta Thunberg, after being frowned upon from Delhi, was forced to delete her twitter post in support of farmers. Meanwhile, her local friend spent a month behind bars.

It is very likely that Kamala Harris had to do the same, apparently beginning to understand the fundamental difference in the statuses of the vice-president of a leading world power and the “free-floating” (that is, not responsible for anything) loud-mouthed leftist.

India’s external actualization of the “human rights issue” threatens to spoil the entire anti-Chinese information and propaganda scene started here by Washington. For in the conditions of a total information campaign against the PRC in connection with the situation with the Uyghurs in the XUAR, it would not be too “comme il faut” to completely turn a blind eye to a similar problem in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Thus inspection trips from ambassadors are appropriate (mainly from Western countries) to the specified state in order to clarify the question whether the Central government is not very much oppressing the Muslim majority here. Apparently, only because in the end it turns out that it is still “not very much”, the Indian government allows this kind of trip.

And in such a tense atmosphere inside India, Lloyd Austin put the “human rights” topic in the center of negotiations with his Indian colleagues in all the above context. The very fact that the defense minister of the leading world power, a gallant general, is forced to engage in such “humanitarian work” is worth mentioning. On the other hand, what is to be done if said work forms the basis of the “general line” of the current party and government of the United States.

In Delhi, Austin was received by his colleague R. Singh’s, national security adviser A. Dawal and, finally, by Prime Minister N. Modi. As is customary in such cases, official reports on the outcome of the talks held are optimistic. In particular, the Pentagon’s comments noted the “cornerstone” character of India’s importance in the American regional military-political strategy.

But, judging by the restrained comments in the Indian press, the guest’s focus on the “human rights” theme nearly brought the whole event to the brink of collapse. Meanwhile, both sides are interested in developing mutual relations. Although in different ways, which is extremely important to emphasize. Moreover, this difference, apparently, will widen, since for India the importance of receiving (significant and urgent) external support in the confrontation with the PRC is decreasing.

This is a consequence of the very timely launched process of resolving the conflict in Ladakh, which put the relationship between the two Asian giants on the brink of a full-scale armed conflict. The disengagement of troops that had begun in the area of last year’s clashes is being further developed in the course of ongoing negotiations between the regional commands of both sides.

In China, they watched with understandable interest the negotiations between the Defense Minister of the main geopolitical opponent and the leadership of the great neighbor, in relations with whom, it should be repeated, acute problems once again arose. As it turns out, neither Beijing nor Delhi needs these problems, whose expected resolution certainly should be attributed to the positive turn of the foreign policy of both India and the PRC. It is this positive turn that allows Chinese experts to believe, that the US will not be able to get India into something more than the current forum-like Quad.

The PRC attaches great importance to the upcoming BRICS summit, which, if the danger from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is reduced, can take place in person (instead of online like last year). Moreover, in India. This means that the leader of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping will appear on Indian territory, with whom Prime Minister N. Modi will be able to talk, as they say, “face to face.” For the first time since 2019.

Moscow should also help Beijing fend off the prospect of Delhi falling into the very close (“friendly”) embrace of the United States. Moreover, apparently, the next attack (undertaken in this case by Lloyd Austin) on a large-scale deal on the purchase of Russian weapons systems by India ended in failure.

India should also be involved in the negotiation process on the solution of the Afghan problem. Besides, Delhi is showing quite understandable interest in this. In connection with the latter, it is important to note that there has been a trend towards improving relations between India and Pakistan, which is very densely present in this problem. This trend is an important element of the overall stress relief process in India’s relations with its neighbors, and above all with the PRC.

In conclusion, the author would like to note that, judging by the results of the visit of the US Secretary of Defense to India, the process of the total “trouncing of Mister Modi” is beginning to falter. Perhaps because Lloyd Austin, although a Catholic, is still not a priest.

But, most likely, Indian leadership itself has finally assessed the scale of the negative consequences of the Washington courtship, partially indicated above, and decided (for now slightly) to slow down its own encouragement. What is right for maintaining strategic stability in the Indo-Pacific.

For India itself, its traditional foreign policy neutralism will avoid unnecessary risks.

Vladimir Terekhov, expert on the issues of the Asia-Pacific region, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.