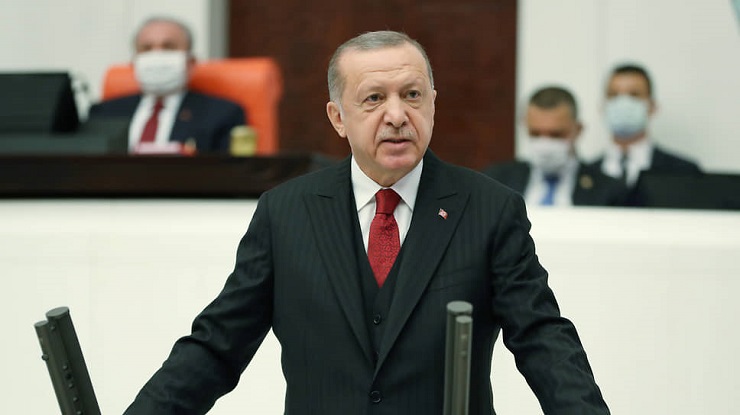

Recently, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has made a number of high-profile statements about how his country is developing. For example, according to Erdogan, Turkey intends to become one of the world leaders in the field of space and satellite technologies, and starting in 2022 the country plans to set afloat one submarine every year.

“Turkey is taking confident strides toward achieving its goal of creating a fully independent defense industry,” the Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB) said in a statement. In recent years, Turkey has begun to gradually provide itself with weapons, independently build ships, and soon it intends to release its first fighter jets. Information about Ankara’s intention to obtain nuclear weapons and the technologies to make nuclear warheads, and in particular from Pakistan, has been repeatedly reported in various media outlets – Erdogan believes that nuclear weapons will help him achieve his geopolitical plans.

Turkey plans to expand the sales markets for its weapons and military equipment. Arms sales to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan are being negotiated, Defense News reported. Military ties between Turkey and Ukraine are actively developing, and contracts have been discussed and subsequently signed to deliver several types of Turkish weapons to this country.

Against the background of Turkey reinforcing its foreign military ties, the possibilities for Ankara to gain access to foreign military technologies are increasing substantially. Pakistani media outlets report that Turkey aspires to establish jointly run production facilities for fighter jets with this country. By gaining access to the “technological innards” of Pakistani JF-17 aircraft, Ankara will eventually gain access to Chinese technologies, which are in wide demand in this model, as well as in Shaheen ballistic missiles.

Ukraine (active protection systems, aircraft and tank engines), Israel (UAVs) and the United States (aviation components) have all helped make a significant contribution to Turkey’s leap forward in military technology. If the deal with S-400 anti-aircraft weapon systems covers more ground, Ankara hopes that a lot of those systems’ technologies will be transferred to it from Russia.

As far as the ties between Turkey and Ukraine are concerned, the military component in them has been actively gaining traction as of late, and Kiev is expanding the scope of its procurement for various weapons from Turkey. Although, as pointed out by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, neither Turkey nor Ukraine can be called advanced in terms of weapons and military technologies, they both have still been ratcheting up the military cooperation between each other particularly intensively as of late – one that is based on a common desire to prevent Russia from dominating the Black Sea, and an overtly anti-Russian position on the Crimea. Analyzing Ankara’s policy, the publication draws the conclusion that Turkey today does not maintain relations with any other adjacent country that are as close as those with Ukraine, using the compatibility inherent in their defense industries. They are currently implementing more than 30 joint projects in the areas of weapons and aviation. In October 2020, the ministers of defense and foreign affairs from both countries agreed on delivering four corvettes to Ukraine, and creating a consortium between Baykar and Ukrspetsexport that is supposed to produce Turkish military drones Bayraktar TB2 in Ukraine, to be subsequently used in the country’s eastern part against pro-Russian militias. In 2018, Turkey already sold six TV2 drones to Ukraine, and last year Baykar developed a new combat drone, Akinci, that uses a Ukrainian engine. Ukraine, which does not currently have any major shipyards, has ordered Milgem-class corvettes from Turkey; these are fitted out with equipment that makes vessels invisible to radars, and the production process for these is supposed to be gradually transferred to Ukraine.

Taking into account that the production of engines remains a very weak spot for the Turkish military industry, one which has scored great successes in recent years, this area of cooperation is developing in a particularly energetic way, and specifically concerning Turkey manufacturing drones, ships, missiles, aircraft, and tanks. Turkey’s largest arms company Aselsan, according to Turkish press reports, is purchasing engines for the recently developed Gezgin cruise missiles from the Ukrainian company Ivchenko-Progress.

This progress is largely due to the personal participation of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in the process; he has met with the presidents of Ukraine ten times since October 2018, including repeatedly with the current president, Volodymyr Zelensky, over the past year.

However, the real picture for bilateral military cooperation between Turkey and Ukraine is far from a rosy one. According to the Ukrainian news agency Defense Industry Courier, the Ukrainian government is receiving information about the impossibility of creating a joint venture in Ukraine to manufacture the Bayraktar Turkish drones. According to various sources, in keeping with its legislation Ukraine should have 50% + 1 share in that kind of joint venture, but Turkey is not happy about this. It wants to own a share in it that is more than 50%.

More news that does not give Ukraine much hope has to be with another joint project: building a series of Ada-class corvettes. Although Ankara is expected to sign this contract with the “Ocean” plant in Nikolayev only in April 2021, there are already significant amendments being introduced to it. For example, according to information from Defense Express received from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, the lead ship in the series will not be built entirely in Turkey, as was previously planned. The Turkish side will only build the hull using its production capacity, and bringing the “technological innards” into shape (including equipping the vessel with all the weapons and electronics systems) will be done in Nikolayev.

Although Ankara would not mind Ukraine allotting land for it to lease on preferential terms, or using Ukrainian cheap labor, it is also in no hurry to share its technologies, let alone localize production.

At the same time, the recent vigorous rapprochement between Ankara and Kiev in the area of military technology that is occurring, and that clearly has an anti-Russian slant, is very critically perceived by Turkish society and the media. In particular, it raises one question: why does the AKP government, which works with Russia in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh, and gains benefit from that, targeting Russia in Ukraine? Why openly do this when, in order to reap similar benefits in the Eastern Mediterranean, the AKP government needs to deepen its relationship with Russia? It can be emphasized that such a policy on the part of Ankara in the interests of the United States in Ukraine, and around the Black Sea is a problematic scheme, and essentially means “shooting itself in the foot” under conditions when the United States is tightening anti-Turkish sanctions.

And another incident of Washington tightening its anti-Turkish policy did not fail to come: Turkish Presidential Spokesperson Ibrahim Kalyn recently announced that the US interfered in a shipment of 30 Turkish-made ATAK attack helicopters to Pakistan. Due to these openly hostile actions taken by Washington, this $1.5 billion contract, which was supposed to be the largest deal in Turkish history for a one-time shipment of defense industry products, will go to China, and Turkey will be the one that obviously loses out.

Vladimir Odintsov, political observer, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.