The victories scored by a range of countries over the past few days, including the bold message delivered by the United Arab Emirates in the form of its Hope probe successfully reaching Mars’ orbit, have roused thoughts about outer space in Turkey. Ankara paid particular attention to the message given on how the Hope probe was successful by Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, who is the Vice President and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, and the ruler of the Emirate of Dubai; he stressed that the purpose of launching the probe is to “give hope to all Arabs, and the fact the we can compete with nations and other people” in the interests of progress and state-building.

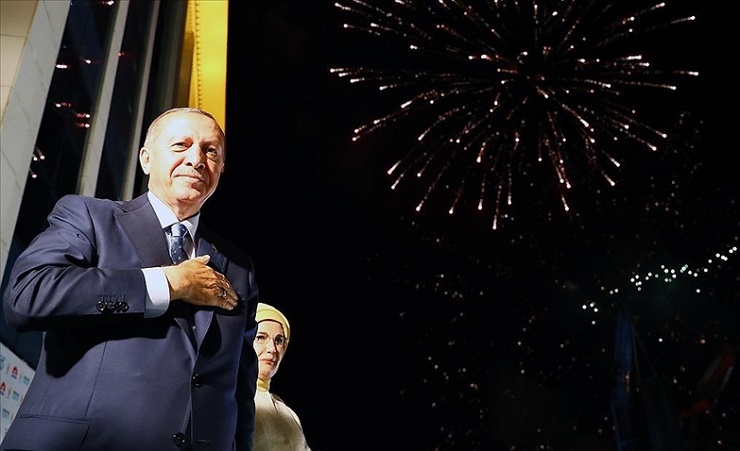

Under these conditions, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has actively promoted a climate of Pan-Turkism for the almost 20 years he has been in the country’s ruling establishment, decided to reinforce that with ambitions of reaching outer space, clearly hoping to use that to further enhance his reputation in the Islamic world, and subsequently become its leader. Speaking on February 9 in Ankara at the ceremony where he announced the ten-year Turkish National Space Program (Milli Uzay Programi), and the opening of the Turkish Space Agency (TUA), Erdogan announced far-reaching plans for Turkey to perform activity in space that could, in his words, “bring Turkey to the top league in the global space race.”

For the first goal, the Turkish president named landing on the moon by 2023, which is the 100th anniversary of the Turkish republic, specifying that the Turkish lunar program will be executed over two stages. The first stage will include the hard lunar landing of an unmanned spacecraft, using a launch vehicle developed in Turkey, that will be launched into orbit at the end of 2023 in the framework of international cooperation efforts. During the second phase, in 2028, a Turkish probe completely developed in-country is slated for launch into lunar orbit using a launch vehicle; this will then make a cushioned landing on the moon.

Turkey’s ten-year space program that was announced by Edogan also includes, in the foreseeable future, constructing its own space vehicle launch site (with help provided by its foreign partners), from which it intends to launch rockets during the first stage of an international cooperation effort, and then on its own over the longer term. As the Turkish newspaper Daily Sabah recently reported, in particular, this means building a Turkish launch site in Somalia, for which the country intends to allocate about 350 million USD as part of the Turkish national space program, which now has a budget of more than 1 billion USD. This African country already has (in Mogadishu) a large Turkish military base, and remarkable cooperation has taken root between the two countries. For example, as part of their strategic partnership Turkey has trained one-third of Somalia’s armed forces.

The Turkish government plans on giving grants to Turkish PhD students that want to go abroad to study astrophysics, and to finance research and development work for Turkish universities in the amount of about 150 million USD.

Turkey’s space program also envisages independently sending a Turkish astronaut off into outer space and entering the ranks of the “big league space players”, which includes the US, Russia, China, and the EU. President of the Turkish Space Agency (TUE) Serdar Hussein Yildirim announced that it was most likely that Turkey would prefer sending its first astronaut into outer space on a Russian-built Soyuz spacecraft, since “It is a reliable spacecraft – we have already become convinced of this. It has proven its worth in space very well.” Nobody knows yet who will be the first Turkish astronaut, but there is a high probability that it will be a woman. Various Turkish media outlets have begun to write about the productive cooperation that Turkey and Russia have been fostering in the space industry in recent years.

The space program disclosed to the public by Erdogan also provides for the country setting up a regional satellite navigation system, expanding its potential to produce missiles, satellites, and space-related technologies, and this is supposed to effectively create an entire space industry, as well as the conditions to possibly become involved in performing commercial activities in near-Earth space. The launch of the first Turkish tracking satellite in 2022 would allow, according to Ankara’s calculations, creating a national Turkish brand in the satellite business.

When considering the space-related ambitions voiced by Erdogan, it would be useful to remember that Turkey is a large country by European standards, with a population of almost 80 million people, ranking 18th in the world in terms of population and 36th in terms of the territory it covers. Its GDP is about 1,500 USD per person, which is quite respectable.

Back in 2010, Hasan Askay, who is the commander of the Turkish Air Force, declared that in the 2020s Turkey would have its own space force and space industry, purely Turkish Göktürk satellites would be launched, and that doing so would meet the country’s needs for gathering foreign intelligence.

In 2011, Turkey launched its first domestic reconnaissance satellite RASAT from the Yasniy Launch Site in Orenburg Region in the Russian Federation; this was completely developed and assembled in Turkey. On December 18, 2012 Göktürk-2 – the country’s second reconnaissance satellite – was launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in China. On December 5, 2016 another Göktürk Turkish reconnaissance satellite was successfully launched from the Guiana Space Center near Kourou, in French Guiana. Turkish media had repeatedly reported that Turkish satellites would be used to serve the interests of the Turkish Armed Forces in the fight against terrorism (meaning primarily the fight against the PKK) in the southeast of the country, and during the military operation in northern Syria (Operation Euphrates Shield). As a result, creating satellites became part of a government-funded program aimed at providing the Turkish army with weapons, equipment and outfits manufactured in the country. Turkey has now managed to achieve a 60% level of self-sufficiency in this area. The race talked about clearly shows that Turkey does not want to lag behind its regional rival, Iran, which has launched several satellites into space in recent years.

In 2013, the Turkish newspaper Vatan reported that Turkey is preparing for a “space war”, and will become the sixth state in the world (after the US, Russia, China, Israel, and Germany) that is involved in developing laser weapons that could likely replace missiles in the future. Back then, the reason for this was the statement made by Minister of Trade and Industry Nihat Ergun that in the years ahead Turkey intended to develop and start producing laser weapons that would be able to track land-, sea-, and air-based targets, and neutralize them.

In March 2015, Turkish Minister of Transport, Maritime, and Communication Lutfi Elvan proclaimed that the first space vehicle launch site and Institute of Space Research would be constructed in one of Turkey’s central provinces. In February 2019, the Turkish President signed a decree establishing the country’s first official space agency (TUA), which will develop the technologies used for launching rockets and space exploration, as well as coordinate the space-related activities performed by other Turkish scientific centers. Ankara plans to fully integrate the Turkish Space Technologies Research Institute (TÜBİTAK – UZAY), the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (the board that regulates the civilian aerospace industry), Roketsan (a major Turkish missile manufacturer) and TÜRKSAT (a semi-private satellite company). For these purposes, up to 20% of their respective budgets have been redirected to create a new agency in an amount of approximately 6 million USD (up to 30 million Turkish liras).

The space industry is new for Turkey, and that is why it is working with multiple countries. According to assessments done by Turkish experts, Turkey’s proximity to the equator with its many plains, could make the country a commercially viable alternative to existing international launch sites, and the Turkish Space Agency’s activities could generate much-needed jobs for aerospace engineering and astronomy graduates – who have very few job options so far. A certain amount of optimism is also inspired by the recently announced government-funded initiative aimed toward bringing scientists back to Turkey by providing funds up to 4500 USD per person per month, for a period ranging from two to three years, so that they can return and start their own laboratories.

Vladimir Danilov, political observer, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.