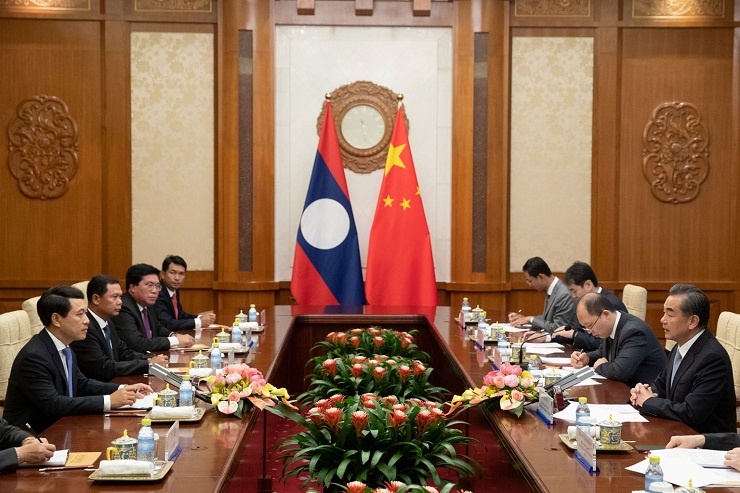

The landlocked Southeast Asian nation of Laos, officially the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and home to a little over 7 million people, has over the past decade built important ties with neighbouring China particularly in the fields of tourism, trade, investment and infrastructure.

Infrastructure Drives Economic Growth

Over a decade ago, those traveling through Laos would find winding roads twisting through the nation’s mountainous terrain. A trip from Kunming, China to Laos’ capital of Vientiane took 3 days. But while traveling through these winding roads, one would notice Chinese construction crews working on modern highways.

Today these highways have cut a trip by road from Kunming to Vientiane to just one day. This has driven economic growth inside Laos including a huge influx of tourism and trade, both of which have more than doubled over the last ten years.

Now, China is near completion of a high-speed rail line through Loas, a nation that previously lacked any rail network to speak of.

Connecting to Laos’ growing transportation networks along its southern borders is an already well developed network of roads and traditional rail in Thailand, along with an already-under-construction high-speed rail network that will link the three countries (China, Laos and Thailand) together, boosting trade and tourism for all three.

The political, economic, and financial ties between China and Laos and Laos’ southern neighbour, Thailand, will create what will be a massive economic corridor through the very center of Southeast Asia and will eventually link up and benefit others in the region including Malaysia, Myanmar and Cambodia.

Western Criticism

Western influence in Southeast Asia is in serious decline. Its inability to propose viable alternatives for even nations eager to balance and hedge their growing ties with China, has left the region turning to others including Russia and Japan.

Instead of finding a way to compete directly with China’s growing influence and economic might, based in its massive industrial capacity, the US and other Western nations have doubled down instead on “soft power” and investment schemes absent of any actual concrete projects.

The focus thus has become not competing with China but simply pressuring nations to avoid national and regional development simply to deny China constructive partners. It is a policy no nation would voluntarily support, thus the growing US-backed political instability and protests seen in Southeast Asia.

The US in particular has been an eager promoter of accusations over what it calls China’s “debt trap diplomacy.” Of course major infrastructure projects incur debt, but it is debt that can be paid off. Even in Western media sources critical of China’s growing influence in Southeast Asia, it is admitted that nations indebted to China, even nations making concessions to China because of growing debt, have provisions included in deals that will allow these same nations to buy back shares in projects and infrastructure in the near to intermediate future.

For Laos, highways and dams are already paying dividends in terms of economic growth. While expensive, high-speed rail moving through Laos will create opportunities and development that are in no other way possible for the country.

The economic prosperity Laos receives in exchange for this infrastructure will eventually make it possible to settle its debts and then some.

As far as balancing against China’s massive military and economic power, Laos’ other major trading partner is Thailand. Thailand’s investments in Laos, which shares history, culture and even linguistic similarities with Thailand, help ensure China is unable to establish an outright monopoly over Laos’ external ties.

For the West, were it serious about competing in Asia, it should participate in the game that is now actually being played; one of balance built through trade, partnerships and infrastructure networks, not a modernised version of Europe’s colonisation in the region last century.

Joseph Thomas is chief editor of Thailand-based geopolitical journal, The New Atlas and contributor to the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.