This, however, does no longer appear to be the agenda. Today’s agenda is protecting America’s consumer markets from an overwhelming presence of Chinese goods–something that directly contributes to the whooping trade imbalance, which stood at $347 billion dollars in 2016. The figure itself speaks for why Trump, a businessman-turned-politician, continues to feel the need to rewrite the Sino-US trade regime.

Notwithstanding what Trump administration is aiming at, China’s own economic policies indicate how it has itself been following a slightly protectionist path, particularly since the recession that hit global market in 2008. On the one hand, it continues to impose high tariff on the goods imported from the US, and on the other, China continues to make inroads in other countries, including the US, through its OBOR economic vision. (read: China continues to make trade deals with a number of US states). Therefore, what Trump sees as a balancing act is nothing but a policy identical to the protectionism China itself has been practicing for quite long time. But the question is: Can Trump really do that?

For instance, trade imbalance, which is also inevitably linked with the given countries’ economic growth, results, as in the case of China, from the countries’ high savings that it uses to reinvest around the world—hence; the ever widening imbalance or gap.

If, therefore, the US want its trade imbalance to reduce, it would have to ask for changing the very structure of China’s economy away from savings and big-ticket infrastructure investments, and towards consumer demand — including for products made both domestically and abroad.

In practical terms this, while certainly asking far too much than what normal courtesy allows, this would mean placing demands on such issues as normally fall purely within the domestic circles of a given economy. That might include, for instance, pushing China to allow more troubled Chinese state-owned enterprises to fail, so that their accumulated profits might be spread through the Chinese economy instead of funnelled toward the purchase of foreign assets.

However, while the US may be able to make such demands from a country heavily dependent upon IMF or World Bank, it certainly is in no position to push China into that direction because of one simple reason: the US is a trade deficient country vis-à-vis China and doesn’t have an upper hand.

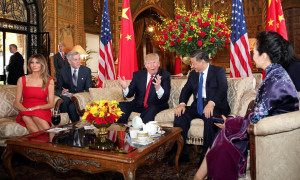

In addition to this factor, China and the US, world’s two biggest economies, have a history of troubled political relations, which are in turn largely shaped by how their economic relations work. The political-economy of their bi-lateral relations is, therefore, such that has a built-in aspect of uneasy relationship.

For Trump, in this context, options are very limited. The US can only go for imposing restrictions on the import of goods from China and what China can do is to retaliate in the same manner.

While some political circles in the US have suggested that the Trump administration should engage China in a bargain vis-à-vis the prospects of the US joining Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank or supporting its OBOR programme, this is unlikely to happen given that the Trump administration continues to look at China as an “enemy” and a foreign policy issue to deal with.

A senior official from the Trump administration was recently reported to have said that, “We aren’t friends, us and China. That is just a downright and dirty fact that we can’t escape. But we can work together. We can cut some deals. They must know North Korea can’t continue to be a global maniac. They must know that they can’t conquer the South China Sea. And they will know soon we mean business.”

More than a real threat, this statement appears to be more of a pressure tactic or an assertion least grounded in reality.

Were the US to go for imposing restrictions on imports from China, which is the most favourite option for Trump, the US would still be unable to deal with China’s investments in the US—investment that has already reached a whopping $45.6 billion and which does help create the jobs Trump has promised.

On the contrary, the US must also consider the fact no other company from both sides will perhaps stand to lose more from a trade war than Boeing, which has collected $60.2 billion from deliveries to China since the year 2000. This figure far outweighs the $800 million to $1 billion that Boeing spends a year on aircraft parts made in China, in joint ventures and other operations.

For Trump administration, therefore, the question of trade imbalance is a tricky one. Mere imposition of tariffs would only exacerbate political and economic relations. What the Trump administration needs is a good bargaining chip, perhaps an offer to join AIIB, than a mere threat of “economic nationalism”—something that is akin to ‘economic isolation’ in the given circumstances of today’s globalized economics.

Unless this happens, the Sino-US trade-war would stay in the limelight and might even refuse to cool down.

Salman Rafi Sheikh, research-analyst of International Relations and Pakistan’s foreign and domestic affairs, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.