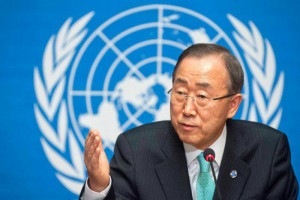

Talks about Ban’s inclusion in the presidential race arise periodically. In 2014, by a wide margin, he dominated a list of people, whom the citizens of South Korea would like to see as the country’s future president. The UN Secretary General’s rating was 39.7%, while that of his closest rival, Seoul’s current mayor Park Won-soon, was almost 3 times less – 13.5%.

At the end of 2015, such talk arose again in the context of his presumed visit to North Korea. At the beginning, on November 16, the South Korean wire service Yonhap, citing highly placed sources in the UN, reported that UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon would visit Pyongyang in the middle of that week, where he would meet with the North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. An anonymous source stated that all preparations had been made, and that “Secretary Ban would not return to New York from Pyongyang without any achievements. . . There is a high probability that this visit will become an important milestone in settling the problem of North Korea’s nuclear capabilities, and other important matters of the Korean peninsula.” Afterwards, the Chinese news agency Xinhua reported the visit, citing the North Korean agency KCNA, expressing the desire that the visit would promote improvement in relations between the Koreas, and indicated the dates – Nov. 23 – 26.

The Secretary General’s press service, however, denied this information. Stephane Dujarric, a spokesman for the Secretary General, spoke about Ban Ki-moon’s schedule, which did not include a visit to North Korea. In the meantime, Dujarric noted that the possibility for Ban Ki-moon’s visit to North Korea was under discussion. South Korea’s Ministry of Unification also stated that no official communications had been received from the UN regarding Ban Ki-moon’s visit to Pyongyang. But on November 24, Ban Ki-moon confirmed his intention to visit North Korea. “I cannot say for now, but I am making efforts to visit the North, if possible, in the near future.” “North Korea is sending positive signals, and we are conferring when it will be a good time to visit the North.”

Finally, on December 7, a UN representative confirmed that discussions with North Korea about an opportunity for the organization’s Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, to visit the country were under way, but “there has been no final decision as yet. When we have made progress, the UN will make an official announcement.” Ban Ki-moon himself has not yet announced his intention to battle for the presidency of South Korea. According to people from his inner circle, Ban is a humble person and feels more comfortable in the diplomatic arena, and not in the area of domestic politics. However, this brings to mind that such decisions are often made “at the last moment, so to speak.”

If Ban returns to Korean politics, then one must consider that he could campaign for the left, as well as for the right. The left, especially in light of discussions about Moon Jae-in’s candidacy, has already expressed interest in Ban Ki-moon’s becoming a representative of the opposition in the 2017 presidential election. Moreover, his relatively moderate stance could help the democrats shake off the leftist image. There is some evidence that such an influential representative of the leftist camp as Kwon No-gap lobbied for Ban’s candidacy.

However, the right would also like to bring the UN’s Secretary General into its ranks. Those around Park Geun-hye have been flirting with Ban and attempting to pull the popular politician into their own camp. The reason is clear: after a president becomes an ex-president, he has no chance to return to power, and then either sits quietly like a mouse, or becomes an object of judicial or another type of persecution. Park Geun-hye has many enemies, and therefore those around her are concerned about maintaining their fraction’s influence after 2017.

In this context, what are Ban’s chances for success? A humble man, he was a good Minister of Foreign Affairs, and is considered in fact not bad an organizer and administrator. There is definite support from both politicians and the public. For that reason, a number of Korean political analysts suppose that if the desire comes to Ban to become the South Korean president, he most certainly will. On the other hand, there are always points for criticism, such as, what has he achieved as the Secretary General, and how much stronger has the UN’s prestige grown under his leadership? It is difficult to please everybody. Additionally, having served as the UN Secretary General, a career as South Korea’s president would be sort of a step downward, and it is unclear whether he would begin to “enshrine” himself in his new position, working outside his limits of competency and communications. So, we will see how well the statements of Ban Ki-moon about not wanting to participate in the presidential race stand the test of time, and observe how events unfold.

Konstantin Asmolov, Konstantin Asmolov, Ph.D (History), Chief Research Fellow of the Center for Korean Studies, Institute of Far Eastern Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.“