Beijing did not appreciate the attempts of the Japanese leadership to prevent (through nationalization) the governor of Tokyo, Shintaro Ishihara’s initiative, which was potentially dangerous for China-Japan relations. He had planned to buy the islands outright and build a port and infrastructure there to station personnel. Under the pressure of Chinese public opinion (lacking thorough knowledge of all the details of the deal with the island), or, perhaps, even deliberately exploiting nationalistic sentiment in the circumstances of an extremely delicate process of the transfer of state power in China in 2012-2013, involving an interparty struggle among the members of CPC, the Chinese leadership decided to not curb the anti-Japanese wave that broke out in China and allowed the relations with its neighbor to worsen.

From September 2012, there was a harshening of anti-Japanese rhetoric in China on the part of the top country officials as well as in the mass media. A number of temporary regulatory measures (in particular, more rigorous customs checks of goods imported from Japan, delayed approval of work visas for Japanese, etc.) were introduced. Contacts with Japan at the ministerial and other levels were suspended on the initiative of the Chinese party. Chinese ships began to regularly patrol the sea in the area of the controversial islands. Chinese planes regularly trespassed Japanese air boundaries (at least twice a month unauthorized Chinese ships would show up in Japan’s territorial waters, while invasions of Japanese airspace occurred at least a hundred times per quarter). China has also embarked on the development of oil and gas fields near the median line of the East China Sea.

On the whole, since autumn of 2012, China-Japan relations entered an era of deep stagnation, which both Chinese and Japanese experts describe as, “It cannot get any worse.” Three issues were at the heart of the Chinese-Japanese disagreements: ownership of the Senkaku islands, the construal of historical events and the visits of Japanese high-ranking officials to the Yasukuni Shrine.

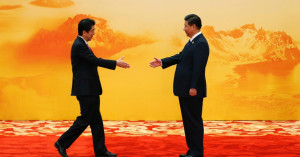

This state of affairs persisted till 2014, when it was quite clearly demonstrated that Xi Jinping’s political policy toward Japan was changing, acquiring more conciliatory undertones. The positive shift in China’s policy signaled a resumption of the dialogue between the ministers of the two countries that had been interrupted in 2012. Akihiro Ohta, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, the first Japanese minister to officially visit China since the “freezing” of formal contacts, arrived in Beijing in June 2014. The visit was followed by a whole range of ministerial meetings, and later the level of meetings propelled to presidential. Negotiations between Yang Jiechi, a member of the State Council of China and Shotaro Yachi, National Security Advisor to PM Abe that were held in Beijing on November 7, 2014, and the achievement of a “four point consensus” opened a new horizon for a private meeting of Xi Jinping and Shinzo Abe during the APEC summit scheduled for November 2014.

And just six months later, in April 2015, the second meeting of the heads of the two countries took place in the course of festivities held in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Bandung Conference. PM Abe was also invited to attend the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Victory of Chinese People’s Resistance against Japanese Aggression and World Anti-Fascist War scheduled to be held in Beijing on September 3, 2015.

Statements, which could be interpreted as the handing of an olive branch symbolizing peace to the Japanese leadership, could be clearly heard in Xi Jinping’s speeches. For example, in his speech at the events organized in commemoration of the Nanking Massacre on December 13, 2014 Xi Jinping noted that the Chinese should not harbor hostile feelings toward the entire Japanese nation for the deeds of a handful of militarists who had unleashed a war of aggression. In May 2015, in the course of a meeting with the Japanese delegation consisting of three thousand heads of local governments and large enterprises, Xi Jinping asked that his cordial greetings and best regards would be passed to all Japanese people, having noted once again that Japanese people had also fallen victims to the war. The Japanese enthusiastically accepted these two speeches of the Chinese leader and deemed them to be a signal communicating a commitment to reshaping the bilateral relations.

What made Beijing moderate its position toward Japan? First, it should be pointed out that reinstatement of formal high-level dialogue fits quite well into the customary pattern of how Chinese practice their foreign policy. When responding to adverse steps taken by a foreign state against it, Beijing temporary ceases political contacts (for a period from a year and a half to two years) with the “offender” and one and a half years later, when the expected edifying effect has been attained, it resumes high-level dialogue. For example, such was the case when there was a 14-month “freeze” of political contacts between Beijing and Great Britain, which followed a meeting of the Prime Minister David Cameron and the Tibetan spiritual leader Dalai Lama in May 2012.

Secondly, from 2013, when China faced a possibility of having to deal with a powerful anti-Chinese coalition with the participation of its neighbors—the parties disputing territories in the South China Sea and the East China Sea, it embarked on the implementation of the “neighboring” diplomacy which, among other things, implied harmonization of relations with its most powerful neighbor—Japan.

Thirdly, the scale of deterioration of China-Japan relations had become alarming: two incidents occurred in the spring of 2014 (in May and June): standoffs between Chinese and Japanese aircrafts, which potentially could have resulted in a crash and the subsequent diplomatic scandal. Since neither Japan, nor China were looking to engage in military actions, which could be triggered by human error during one of the standoffs between aircrafts or ships, there was a real need to ease the tension in the China-Japan relations.

Fourthly, the fact that political disagreements had started adversely affecting the trade and economic relations of the two countries could have also contributed to the change in the Chinese policy toward Japan. At that time the goods turnover was dropping, the volume of operations of Japanese business in China was shrinking, and there had emerged a stable trend of reduced Japanese direct investment in China. In December of 2013, the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation published a report informing that China had been moved down from the first to fourth position on the list of countries receiving Japanese investment. From January to October 2014 Japanese direct investment in the Chinese economy decreased by 42.9% in comparison with the same period of the preceding year. The flow of Japanese tourists traveling to China had significantly reduced: In April-September 2013, the sales of package tours to China dropped by 75.2% in comparison with the same period of 2012.

And fifthly, by 2014 Xi Jinping had already concentrated all the power in his hands and there was no real need to employ nationalism as a means of consolidating power. China could afford to somewhat reduce its pressure on Japan and disregard nationalist public sentiment.

However, there are not so many reasons for optimism as far as the possibilities of full-fledged normalization of China-Japan relations are concerned even in light of the relative moderation of Xi Jinping’s policy toward Japan. All the problems inherent in the bilateral relations remain unresolved and there is little chance they could be effectively settled in the foreseeable future. It is also highly unlikely that one of the parties involved in the disputes will be willing to make concessions to the other party on the issues in question. Nevertheless, the observed improvement in the political dialogue in the present situation is evidence that significant progress in China-Japan relations has already been made.

Yana Leksyutina, Ph.D. in Political Sciences, Lecturer at St. Petersburg State University, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”