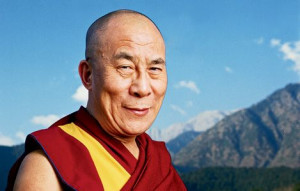

The reason why the role and place of the Buddhist spiritual leader is briefly looked at is due to his recent quite preposterous statements (which incidentally is quite a few) on the subject of reincarnation (that is the spiritual transfer of leadership) of the next Dalai Lama. These statements have provoked strong reactions in China. At the beginning of March the Dalai Lama XIV spoke in favour of ending in contemporary Buddhism the institution of the High Lamas but allowing the faithful to resolve the issue by referendum.

There was immediate doubt on the technical viability of such a referendum. He furthermore did rule out the the chance of reincarnating as a woman or even a bee. Similar “apolitical” arguments provoked the anger of Beijing, accusing the Dalai Lama XIV of a “double betrayal” of his earthly motherland and of his faith.

The reality is that the Chinese government does not want to allow the process for the election of a new Dalai Lama by any means to “run its course”, taking into consideration the nuisance he has been in the international arena to China and in particular in relation with India’s present-day Buddhist leader. One should take note that even though the Dalai Lama XIV has moved away from secular activities since 2011, leaving the post of the “Tibetan government in exile” and seemingly focusing entirely on the spiritual realm, his former impact on the state of the Chinese-Indian relations has not diminished. To be fair, he only plays a small role in it.

Because who is able to separate the everyday worldly things from the spiritual and if you must busy yourself looking for that dividing line. When it generally permeates in a predominant fashion everything (including religion, culture, policy) and all profaned pop-culture? The answer to these age-old questions depend on the view of the seeker. For example, from the point of view of the Dalai Lama XIV and the Indian government who gave him shelter at the end of the 50s, the visits of the Buddhist leader to the mountain village of Tawang have not relation to the current Sino-Indian political squabbles.

As he visits one of the most important Buddhist shrines: a monastery built in Tawang at the end of the XVII century at the behest of the fifth Dalai Lama. But the Chinese government views all these official Indian explanations as excuses to cover up his true purpose of “consecrating the unlawful occupation” around the Tawang district, now included in the “so-called Arunachal Pradesh” that Beijing identifies as “South Tibet, a native Chinese territory”. Such territorial disputes, over a distance of 4 thousand kilometres on the general border, are just some of the activities that cause negative reactions from one side to the other.

However disputes and incidents in the area, in regards to these rather small territories, are a diversion to the much bigger fundamental problem in the relationship between China and India, which originated in the early 20th century (i.e during the period of domination of “British India”) and that independent India inherited. We are talking about the de facto status and role of the vast territory of Tibet in the Sino-Indian relations.

Just to immediately clarify: the problem of the “status of Tibet” has been non-existent since 2003 on a bipartisan official level. In fact, India has officially recognized the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) as an integral part of China. In response, Beijing recognized the Indian part of the former principality of Sikkim.

Not that the “Tibetan problem” as such existed for the Chinese in the late 50s during which a part of the People’s Liberation Army occupied all the strategically important regions of Tibet, thereby ending word games like “suzerainty is sovereignty” Beijing over Tibet, that was still under the administration of “British India”. The moment of the Chinese military operation in Tibet was chosen exceptionally well. The USA had gotten well bogged down in Korea a few months before and the Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru could not rely on anyone in that moment as a source of potential support.

Therefore the present-day reproach of “weakness” coming from certain representatives of an extremely influential part of the Indian establishment is hardly fair. It’s appropriate to mention that for the transatlantic “simpletons abroad” Korea was not the first nor the last trap that someone helpfully laid for them. And each of which they felt obliged to please. This was followed by Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria… Both the CIA and the Kuomintang intelligence were prepared in 1958 for action from Tibetan refugees.

The anti-Chinese uprising broke out with their active participation in March 1959 in Tibet. The Liberation Army went into the troubled areas of Tibet provoking a new wave of refugees coming onto the Indian territory including the Dalai Lama XIV. The very monastery in Tawang was the first refuge on Indian territory for the Dalai Lama XIV. Thus the visits to the monastery has personal value to the Dalai Lama XIV. There are an estimated 100 thousand Tibetan refugees in India. Most of them, the “Tibetan Government in Exile” as well as the Dalai Lama’s residence is located in Dharamsala in Northern India, in the immediate vicinity of the TAR.

The presence of Tibetan refugees, their “government” and the residence of the spiritual leader in India creates problems with China on the one hand but at the same time acts as a lever of pressure and counterbalances Beijing’s foreign policy toward Pakistan. It is not a “weapon” that India uses often. In 2008 the Indian government issued guarantees to Beijing that the Indian Tibetan protests against the Summer Olympics in China will not go beyond what is acceptable for China.

It is important to know that despite the official position of the Indian government on the identity of Tibet, the “Tibetan issue” is still very much in the forefront of political thinking in the upper part of the Indian establishment. According to Russian and foreign experts, the problem has generally remained de facto in the centre of the whole system of Sino-Indian relations and is in particular the main reason behind the defensive construction on both sides of the border. The most common agreement is that “the greatest threat to the Indo-Chinese relationship arises from widely differing views of the history and ultimate destiny of Tibet.”

The sentiment in relation to the Tibetan problem in the above mentioned part of the Indian establishment is adequately reflected by the position of Arun Shouri, respected journalist and member of government between 1998-2004 of the right wing party “Bharatiya Janata (returned to power in May 2014). In connections with the riots that took place in Tibet in 2008, he wrote in the beginning of the next year:

“The danger will not go away just because we refuse to see it. The security of India is firmly intertwined with the existence and survival of Tibet as a buffer state…” Thus the actions of the Dalai Lama XIV in India and in the international arena, whom the Chinese is determined to call a “separatist”, is not the root cause of the complex state of Sino-Indian relations. It rather highlights them as rather “earthly” reasons.

Vladimir Terekhov, expert on the Asia-Pacific region, specially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.