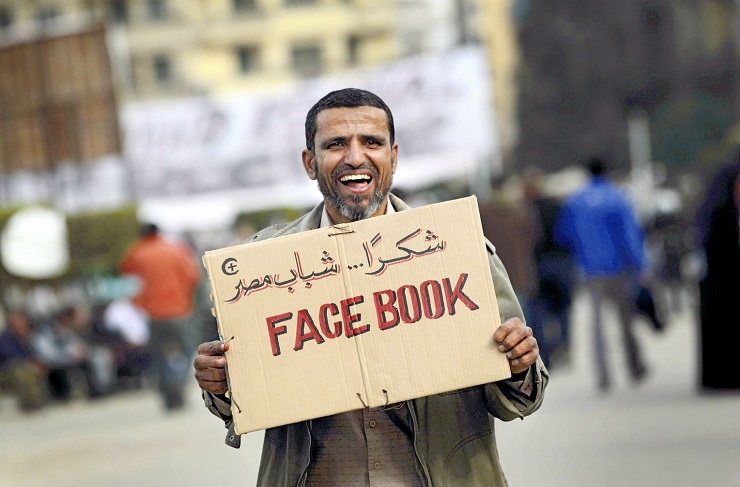

The Intelligence Community, regardless of regime type, has famously always tried to co-opt and ultimately adopt advancements and evolutions in technology, especially in terms of media. Newspapers, radio, and television have long been appropriated in order to influence, massage, and outright manipulate messages and events important to the national interest. Often the question is not so much whether a country’s intelligence community engages in such activity but rather how explicit and open will it engage (from a softer, less visible approach in democratic states to a harder, more obvious method employed by authoritarian states). My position will argue why social media like Facebook and Twitter are in fact resistant to authoritarian co-optation and are uniquely structured to be only an effective grassroots tool for social disruption and civil disobedience. They are poor tools for hindering mobilization because of the structural nature of both social media and authoritarian government. While these instruments of new information and communication technology indeed seem capable of inspiring and impacting recent international and transnational affairs (i.e. the Arab Spring), it will be shown how these technologies have certain limitations, not only in terms of governmental use but also in terms of protest. Indeed, social media tools are best when considered only facilitators of dissent and mobilization but not guarantors of political results or systemic change. As such, opponents and proponents of the political power of social media are often overstating their respective cases.

This article emphasizes the need to carve out a more modest but still important path for social media when it comes to revolution, dissent, and potential democratic transition: it is true that social media does not answer everything as to why modern revolutions take place. However, it is also true that social media is the best facilitator for such uprisings because of the structural nature of not only social media but also of authoritarian governments themselves. Social media is at its most powerful and most compelling when it is seen purely as a facilitator of popular mobilization. When that power is expanded to try and make social media a guarantor of results and the consolidator of new democracy, then the arguments have gone too far and make promises that reality is not able to keep. What the present work criticizes is the somewhat unconscious positioning of social media as an end goal-producing outcome, rather than as an open-ended process. Process does not and cannot independently guarantee outcome. Therefore, both the critics and supporters of social media’s power have been judging unfairly: the facilitator of protest mobilization should not be condemned or lauded for how large, how fair, how complete, or how quick democratic end results emerge from said mobilization.

In other words, asking if social media literally leads to consolidated democracy is simply asking the wrong question. This should not be considered ammunition to be used exclusively against social media critics: this article also chastises its more rabid supporters. Social media certainly has the capability to be the channels through which protestors can identify goals, build solidarity, and organize demonstrations. The problem is with those who wish to turn the high-efficiency of social mobilization channels into a firm and lasting democratic foundation from which new consolidated democracies can be built. The channels of social media alone cannot accomplish this task. Social media does not excel in the hands of authoritarian government because of how systematic, formalized, rigid, and fearful of free-flowing exchange it is. Yet studies show that even democratic governments have trouble coping with the speed, nakedness, and spontaneity of social media information flow. As a result, they try to force social media into their own familiar structure, just as authoritarian regimes do. The end result of these similar efforts is the same – neither effectively utilizes social media as well as groups who organize for dissent. Just how much this is caused by structure, and how potentially axiomatic this argument could prove to be, will be explicitly elaborated in the following section with the introduction of the Antithesis matrix.

The Antithesis Matrix: Why Spies Don’t Tweet

Categorization SOCIAL MEDIA AUTHORITARIAN GOVT

|

TEMPO |

Fast-paced |

Glacial |

|

REACTION TO STIMULI |

Malleable, Adaptable |

Rigid, Intractable |

|

ORGANIZATIONAL ETHOS |

Creatively disorganized |

Bureaucratically hyper-organized |

|

CHIEF TARGET AUDIENCE |

Young |

Old |

|

ATTITUDE TO NEW INFO |

Impressionable |

Reluctant |

|

CAUTIOUSNESS |

‘Riskophile’ |

‘Riskophobe’ |

|

OPERATIONAL CAPABILITY |

Agile |

Clumsy |

|

GENERAL STRUCTURE |

Anarchical |

Hierarchical |

|

STYLE |

Informal |

Formal |

|

IDEAL PURPOSE |

FOMENT DISSENT |

PRESERVE STATUS QUO |

The final category, ‘ideal purpose,’ is perhaps where the Antithesis matrix causes its biggest controversy. For the first time an attempt has been made to definitively categorize and conceptualize the structure of social media with the distinct purpose of comparing it to the structure of authoritarian government. Having gone through nine explicit categories that encompass their structural natures, it becomes clear that the ideal purpose suited for social media is to foment dissent while the ideal purpose suited for authoritarian government is to preserve the status quo.

The nature of social media is in antithesis to the nature of authoritarian government. Civil disobedience, dissent, protest, social mobilization, all aiming to enact change and fight the system, are perfectly facilitated within the structures of social media. Efforts to counteract such movements require an opposing structure. As such, using social media to undermine or constrain dissent facilitated by social media is simply the wrong tool for the wrong job. At their very mildest, authoritarian regimes are simply bureaucracies run amok. They are bureaucracies that live to ensure the survival of their own bureaucracies. They are status quo machines. As such, authoritarian regimes would be able to effectively maximize the power of social media only if they altered their very structure and nature. This article simply makes explicit what should be common sense: such change will not occur.

The Antithesis matrix is not a predictor of where revolutions will happen. It is a reminder that societies embedded with multiple forms of social media have the potential to facilitate protest and civil disobedience if other factors on the ground warrant such behavior. It is also a reminder that those regimes where it is likely to have those motivating factors in place should not feel too overconfident in their ability to constrain or co-opt that social media-inspired mobilization: for the matrix shows that the general population in authoritarian states tends to be much more adaptable, energetic, creative, agile, and not unnerved by social chaos and temporary anarchy. While social media cannot be a guarantor of democratic consolidation, its presence does guarantee the opportunity for citizens in authoritarian regimes to mobilize for democracy. Steve Jobs said that it is not faith in technology. It’s faith in people. Long-term democratic success or failure depends upon them, not upon the process.

Dr. Matthew Crosston is Professor of Political Science and Director of the International Security and Intelligence Studies program at Bellevue University, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.