It would be premature to draw even the most approximate conclusions on the Arab Spring, which is still under way both in terms of the depth of the political processes taking place in each of the above countries and in terms of the increasing number of states being involved in the sequence of “revolutions”. There is a real threat that the crisis might even spread beyond the Arab world, in particular, to Turkey, Iran, the Transcaucasian and Central Asian countries. Prerequisites for such developments do exist.

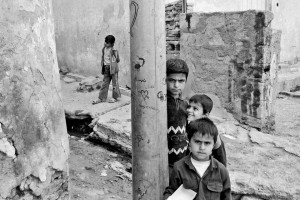

In the situation that is emerging today, an increasingly important role in the region is played by the Kurds – a 40-million people that, due to the force of external circumstances, has been deprived of its statehood and divided by the borders of four states: Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. A few million Kurds live in Europe, the Trans-Caucasus and the CIS countries, including Russia. Until recently, the Kurds constituting national minorities in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria have been, in every possible way, oppressed by the central authorities, which have been pursuing the policy of their forced assimilation and relocation, imposing severe restrictions on the use of the Kurdish language etc.

The Iraqi Kurds (about 6 million people) were the first to get rid of the status of second-class citizens by making sure that their status as a federal entity with broad rights and powers was enshrined in the new constitution of Iraq. The country’s three northern provinces (Erbil, Dahuk and Sulaymaniyah) making up Iraqi Kurdistan are developing rapidly and confidently, restoring the infrastructure, economy, agriculture, the systems of livelihood, health care and education; they are successfully solving social problems. There is a favourable legislative climate conducive to the influx of foreign investments, the accreditation of new diplomatic, trade missions and transnational corporations. In 2014, it is planned to independently produce oil and gas and export them via Turkey to the world market. The region has become a kind of oasis of stability and security against the backdrop of the ongoing terrorist war between the Iraqi Arab Sunnis and Arab Shi’ites. Moreover, president of Iraqi Kurdistan Masoud Barzani has acted as a mediator in the settlement of the protracted government crisis, which had been going on in the country for nearly a year, and contributed to reaching consensus between the major Iraqi political blocs of the Arab Shi’ites and Sunnis. The Kurds have quite a decent representation in the central authorities in Baghdad: the President of Iraq is one of the reputable Kurdish leaders Jalal Talabani; the Kurds hold 6 ministerial posts, including the post of foreign minister, and have established a substantial Kurdish faction in the federal parliament. According to the existing law, the Kurds are entitled to 17% – in proportion to their number – of the total export of Iraq’s hydrocarbons. You cannot say that there are no problems or contentious issues between the region and Nouri al-Maliki’s government, but all most acute contradictions are discussed at the negotiation table and have not so far taken the form of open conflicts. The leaders of the Iraqi Kurds look at the situation in the country and region realistically and are not advocating for their secession from Iraq. The Kurds could be prompted to proclaim independence only by a further deterioration of the armed confrontation between the Arab Sunnis and the Arab Shi’ites or by the natural collapse of the state due to the ethno-sectarian divide into three enclaves (northern, central and southern).

Paradoxically, the civil war in Syria has significantly improved the political position of the Syrian Kurds. In the face of the possibility of losing power, the government of Bashar al-Assad had to make significant concessions for their Kurds (whose number is estimated to be about 2.5 million people). At last, the Syrian citizenship was granted to the 300 thousand Kurds who had been stripped of it during the rule of Hafez al-Assad. Hundreds of Kurdish political prisoners were released from prisons; the government troops were withdrawn from almost all areas with compact Kurdish population. These measures contributed to the fact that the Syrian Kurds adopted a position of neutrality in the inter-Arab conflict in the country and even created self-defence forces in order to prevent Islamist militant groups from invading their territories.

Recently, the national movement of the Syrian Kurds has consolidated considerably. If before March 2011 Syria had about 20 Kurdish political parties and social organisations that were acting separately and in a semi-legal manner, by now they have consolidated into two main political blocs: the Kurdish National Council and the Democratic Union Party (its military wing – the People’s Protection Units). Moreover, thanks to the help from Iraqi Kurdistan President Masoud Barzani, it has been possible to establish the Kurdish Supreme Committee, the board of which is trying to coordinate the activities of all Kurdish political forces in Syria. Besides, some of the leaders of the Syrian Kurds belong to foreign diasporas and live permanently in Europe and the United States. The most radical of them, such as, for example, representative of the leadership of the Democratic Union Party (DUP) Salih Muslim, advocate for the establishment of a Kurdish autonomy in Western Kurdistan or even a federal entity of the Iraqi Kurdistan type. One of the autonomous Kurdish districts has already been declared in the area of Qamishli. But the majority of the Kurdish activists look at the situation in the country realistically (fragmentation of the Kurdish enclaves) and are calling upon their fellow tribesmen to continue, if possible, adhering to neutrality in the inter-Arab conflict. The Islamist militants’ attacks and reprisals against the civilian Kurdish population have further consolidated the Syrian Kurds in the struggle for their rights and freedoms and accelerated the process of creating self-defence forces. However, their leaders are not refusing to participate in the Geneva II peace conference and continue the dialogue with the supporters of Bashar al-Assad and the opposition. The Kurdish leaders are hoping that, whatever the outcome of the civil war, they will be able to ensure that Damascus fulfils the Kurds’ main demands, which can be summarised as follows:

– constitutional recognition of the Kurdish people as the second largest nation in the country;

– putting an end to discrimination against the Kurds on ethnic grounds and to their forced assimilation;

– recognition of the national, political, social and cultural rights and the particularities of the Kurds;

– providing an opportunity to form local authorities and power structures in the Kurdish enclaves from the Kurds themselves, proportional representation of the Kurds in the central legislative and executive authorities;

– lifting the restrictions for the Kurds on holding public and military service positions, obtaining higher education etc.;

– introducing primary, secondary and higher education and the mass media in the Kurdish language;

– accelerated social and economic development of the most backward Kurdish areas.

(To be continued…)

Stanislav Ivanov, senior research fellow at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Candidate of Historical Sciences, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.