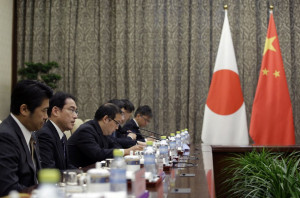

Considering that because of rocky Sino-Japanese relations, high-level meetings between the two countries are a rarity and summit meetings have not been held for many years, both Beijing and Tokyo perceived this visit as a milestone event.

In Japan, Fumio Kishida’s visit was regarded as an opportunity for “testing the water”, where “the water” personified the dominant political sentiment prevailing in the “body of water” (China).

It was expected that after his trip to Beijing, Mr. Kishida would fill in his boss, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, on whether the “body of water” was ready for him to “take a deep dive,” i.e., go to China with the first official visit since the time he was re-elected Prime Minster at the end of 2012.

Right before the arrival of the honored Japanese visitor, Chinese Global Times published an article with a remarkable title: Time for Tokyo to Recalibrate Foreign Policy.

The article listed three major groups of problems—legacy of WWII, territorial disputes and geopolitical games—inhibiting the development of productive bilateral relations. All these problems were covered by NEO on many occasions.

The bilateral relations deteriorated almost to the post-WWII level in the fall of 2012 when Japanese government allegedly “bought” three out of five Senkaku islands located in the East China Sea (and contested by China) from some individual.

And only in fall of 2014, at an APEC summit held in Beijing, Xi Jinping and Shinzo Abe met again. At that time, the meeting was construed as a sign of warming of the bilateral relations. Today it is evident that thawing has been inadequately slow, to say the least. The same article described the current state of relations using a tactful, catering to the occasion (the visit of an honored Japanese guest) word “backwater.” This definition would work fairly well if the picture is further dramatized with a layer of thick gray clouds.

The “clouds” started gathering two-three years ago, when Japan intensified its activities in the South China Sea—the region that saw an escalation of the politico-military confrontation between China and a number of its neighbors on the account of territorial disputes. And the role of the wind, moving the clouds in the direction of China, is performed here by China’s geopolitical opponents: the USA and now also Japan.

In the anticipation of Mr. Kishida’s visit to Beijing, Chinese experts once again expressed concern over the possible “Japan’s intervention” in the existing disputes “undermining Sino-Japanese relations”. Lately, there were more reasons for such concerns. Among the most recent ones, there was the appearance of a group of Japanese navy combat ships (a submarine and two missile destroyers) in the South China Sea in the first half of April, right when the US and the Philippines (with symbolic participation of Australia) were conducting a scheduled Shoulder to Shoulder military drill. Although Japanese navy was not an official party to the drill, its appearance there was hardly accidental, especially since the Japanese ships departed from the Philippine Subic Bay to moor in the Vietnamese port of Cam Ranh Bay. It was nothing else, but an explicit demonstration of support for Viet Nam—one of the toughest opponents of China in the South China Sea disputes.

What appears to be curious is that on his way from China, Mr. Kishida made several stops in the countries, opponents of China in the South China Sea controversy. Viet Nam, which was last on the list, but, most probably, first in significance, has been turning into a favorite “port of call” for the members of Japanese government, including Japanese Minister of Defense.

Economic interests of the two countries play the role of a key factor slowing down the rate of deterioration of their bilateral relations. In the recent years, the volume of bilateral trade amounted to an impressive $280 bn (despite the trend toward a decline). China ranks first (somewhat surpassing the US) among Japan’s trading partners. Japan occupies the fourth line on the list of China’s trading partners (overtaken by the EU, the USA, and the bloc of ASEAN states).

The overall deterioration of the political relations, amplification of anti-Japanese sentiment in China and increasing Sinophobia in Japan negatively affect the inflow of Japanese investments to the Chinese economy. An annual reduction of the volume of incoming investments reached approximately 30% in the last two years.

As odd as it might seem, increasing mutual apprehension does not hinder a rapid development of the bilateral tourism. About 4.7 million Chinese visited Japan in 2015 (a 50% increase to compare to the two preceding years) where they spent around $12 bn. China forecasts that in 2020, the year Tokyo will be hosting Summer Olympic Games, some 10 million Chinese tourists will visit Japan. Chinese experts express an opinion that the evolving “peoples diplomacy” paired with considerable mutual economic interests will help downplay negative consequences of the political games the politics of both countries have been playing in the recent years.

It seems that despite persistent mutual resentment, the parties come to understand the risks associated with deepening confrontation. In their closing statements, Chinese and Japanese ministers underscored the necessity to “work harder to improve ties”.

The ministers, however, did not discuss the issue of a prospective visit of PM Abe to China. According to the information released in press, this matter will be clarified somewhere at the end of May, when, as many believe, National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister of Japan Shotaro Yachi will meet with a member of the State Council of China Yang Jiechi.

Vladimir Terekhov, an expert on the Asia-Pacific region, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.“